How to account for cross-linguistic variation in fragment answers? Tanja Temmerman

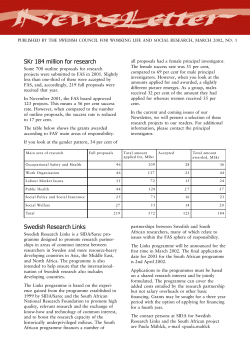

How to account for cross-linguistic variation in fragment answers? Tanja Temmerman (Leiden University/LUCL) A. Outline This paper investigates Dutch fragment answers (FAs) in comparison to their English counterparts. While the former are insensitive to islands and can in general be embedded, the latter show locality effects and only occur in root contexts. I argue that the difference in island sensitivity follows naturally if Dutch FAs are given an account parallel to that of sluicing, i.e. fronting to Spec,CP and TPellipsis. I also show that there is variation among the Dutch embedded FAs: one type of embedded FA, which is – unlike the other Dutch FAs – island-sensitive, moves from Spec,CP to matrix Spec,vP (prior to the TP-ellipsis). The analysis provides support for (a version of) the PF-theory of islands, according to which island sensitivity is due to non-deletion of PF-uninterpretable traces. Finally, I argue that the WH/sluicing correlation makes the correct predictions regarding the (non-)embeddability of English and Dutch FAs. B. Fragment answers in Dutch & English: basic properties B.1. Definition FAs, both in English and Dutch, are answers consisting of a non-sentential XP with the same propositional content and assertoric force as a full sentential answer (cf. Merchant 2004). (1) Q: Wie gaat de wedstrijd winnen? 'Who is going to win the contest?' A: Eva. (= Eva gaat de wedstrijd winnen.) 'Eva.' (= 'Eva is going to win the contest.') B.2. Ellipsis Merchant (2004) argues that English FAs are derived from full sentential structures by ellipsis (PF-deletion), as the FA exhibits connectivity effects identical to those shown by its correlate in a non-elliptical sentence. This is also true for Dutch (root and embedded) FAs, cf. (2) with variable binding. (2) Q: Wat vindt elke politicusi uiterst belangrijk? 'What does every politiciani hold in high regard?' A: Zijni imago. / Elke politicusi vindt zijni imago uiterst belangrijk. 'Hisi image.' / 'Every politiciani holds hisi image in high regard.' B.3. Movement Merchant (2004) also provides several diagnostics to show that a FA has A'-moved prior to ellipsis (i.e. the elided clausal structure hosts the trace of the movement operation). One such diagnostic is preposition stranding: while P-stranding languages like English allow both PP and 'bare' DP FAs to WHquestions with a preposition, in non-P-stranding languages like Dutch only PP FAs are possible, cf. (3). (3) Q: <Naar> wie was Peter <*naar> aan het kijken? 'Who was Peter looking at?' A: a. Naar Lisa. b. * Lisa. '(At) Lisa.' C. Fragment answers in Dutch & English: main differences C.1. Dutch, but not English, FAs are island-insensitive Whereas English FAs obey island constraints – as expected if they involve A'-movement – Dutch FAs do not. Morgan (1973) and Merchant (2004) use implicit salient questions (yes-no questions with an intonation rise on an XP in situ) to test for the island sensitivity of FAs. Example (4) shows that Dutch, but not English, FAs can violate a relative clause island. (4) Q: Willen ze iemand aannemen die GRIEKS spreekt? 'Do they want to hire someone who speaks GREEK?' A: Nee, ALBANEES. * 'No, ALBANIAN.' Sluicing, i.e. clausal ellipsis leaving a WH-remnant, is island-insensitive as well (Ross 1969; Merchant 2001). (5) Ze willen iemand aannemen die een Balkantaal spreekt. – Welke? 'They want to hire someone who speaks a Balkan language. – Which one?' C.2. Dutch, but not English, FAs are embeddable The question in (6) allows for a number of different embedded FAs in Dutch (cf. also Barbiers 2002). Embedded fragments of 'type 1' (A1) follow the matrix past participle, while 'type 2' FAs (A2) precede it. FAs like (A3) are ambiguous between type 1 and type 2. Their English counterparts are ungrammatical (cf. also Morgan 1973; Merchant 2004). (6) Q: Wie dacht je dat de wedstrijd zou winnen? 'Who did you think would win the contest?' A1: Ik had gedacht Eva. A2: Ik had Eva gedacht. A3: Ik dacht Eva. * 'I (had) thought Eva.' Like root FAs in Dutch, the embedded fragments of type 1 are not sensitive to islands, as illustrated in (7a) with an adjunct island. FAs of type 2, on the other hand, do obey locality constraints, cf. (7b). This crucial difference indicates that the latter type of FA should be given a different analysis. (7) Is Ben gekomen omdat hij ROOS wil versieren? 'Has Ben come because he wants to seduce ROSE?' a. Nee, ik had gedacht / zou denken LISA. * 'No, I had thought / would think LISA.' b. * Nee, ik had LISA gedacht / ik zou LISA denken. * 'No I had LISA thought / would LISA think.' D. The analysis of Dutch & English FAs and the PF-theory of islands D.1. The analysis of root FAs (and sluicing) The theoretical approach adopted here is a Merchant (2001, 2004)-type implementation of ellipsis in terms of the syntactic feature [E]. In sluicing, [E] is merged with the C°-head whose TP-complement is to be elided (cf. Merchant 2001, van Craenenbroeck 2004). Although it is not entirely clear why or how, it seems that the presence of the [E]-feature on C° requires that this head always remains empty, even in languages which allow doubly-filled-COMP-filter violations in non-elliptical embedded WH-questions, such as various Dutch dialects. This is illustrated in (8). (8) Ben wil een meisje versieren, maar ik weet niet wie (*dat). 'Ben wants to seduce a girl, but I don't know who (*that).' The analysis of sluicing is schematically represented in (9): [E] is merged with C°, the WH-phrase moves to Spec,CP, and TP is elided. Much recent work on ellipsis adheres to the PF-theory of islands. For instance, the basic conception of Merchant (2004, 2008) is that traces of island-violating movement are PFuninterpretable (marked with *) and cause a PF crash if they are not eliminated. In (9), TP-ellipsis deletes all defective traces, yielding a PF-interpretable object. This derives the island insensitivity of sluicing. (9) [CP WH1 [C° [E] ] [TP … *t1 … t1 …]] To deal with the difference in island sensitivity between English sluices and FAs, Merchant hypothesizes that English FAs target an additional CP-layer, leaving a trace in an intermediate Spec,CP, cf. (10a). In (10a), one *-trace is not deleted by TP-ellipsis, causing a PF-crash. Dutch FAs resemble sluicing in being island-insensitive. Hence, we can assume that they are simply the non-WH-equivalent of sluicing, cf. (10b). (10) a. [CP XP1 C° [CP *t1 [C° [E] ] [TP … *t1 … t1 … ]]] b. [CP XP1 [C° [E] ] [TP … *t1 … t1 …]] Although this analysis nicely accounts for the differences in island sensitivity, it is not that clear what the motivation for the extra movement step in English FAs is, other than the need for a non-elided trace. However, Dutch embedded FAs provide evidence that this PF-theory of islands is on the right track. D.2. The analysis of Dutch embedded FAs Embedded FAs never surface with dat 'that', although this complementizer is obligatorily present in non-elliptical subclauses, cf. (11). If the structure of the CPcomplement of denken 'think' in (11a) resembles the structure in (10b), with the C°-head hosting an [E]feature, the absence of dat is expected, on a par with the absence of an overt complementizer in sluicing. I assume that the structure of the island-insensitive FAs of type 1 is indeed similar to that of root FAs. (11) a. Wie heeft het gedaan? – Ik zou denken <*dat> Eva <*dat>. 'Who has done it?' – * 'I would think Eva.' b. Ik zou denken *(dat) Eva het gedaan heeft. 'I would think that Eva has done it.' Barbiers (2002) analyzes FAs of type 2 as involving (A'-)Focus-movement of XP (Eva in (6)) to the matrix Spec,vP. This fronting is not at all unmotivated, as it is also allowed in non-elliptical sentences in Dutch: (12) Ik had [Eva] gedacht dat zou winnen. 'I had thought that Eva would win.' Barbiers claims that this fronting is followed by PF-deletion of the embedded CP. Merchant's PF-island theory provides a diagnostic for deciding whether type 2 FAs involve CP-ellipsis, or TP-ellipsis like the other Dutch FAs. Compared to FAs of type 1, type 2 FAs involve an extra movement step (to Spec,vP), leaving a trace in the embedded Spec,CP. While CP-ellipsis deletes this trace, TP-ellipsis does not. If the moved XP crossed an island node, a non-elided *-trace would cause a PF-crash. Thus, CP-ellipsis predicts type 2 FAs to be island-insensitive, while TP-ellipsis predicts island sensitivity. Type 2 FAs differ from the other Dutch FAs exactly in obeying locality (cf. section C.2), showing that the latter prediction is correct. E. Why Dutch, but not English, FAs are embeddable Both English and Dutch exhibit (at least) two types of clausal ellipsis: sluicing and FAs. However, while embedded sluicing occurs in both languages, only Dutch FAs are embeddable. The key to solving this puzzle is van Craenenbroeck & Lipták's (2006) WH/sluicing correlation (WhSC): ''the syntactic features that [E] checks in a certain language are identical to the strong features a WH-phrase checks in that language.'' A precise analysis of English and Dutch WHmovement requires that the CP-domain be split up in two functional projections: the low CP2 is related to operator-variable dependencies, the high CP1 to clause typing (cf. Culicover 1991; den Dikken 2003; van Craenenbroeck 2004). Following the literature, I claim that English and Dutch overt WH-movement do not necessarily target the same CP-projection. overt WH-movement [E] ellipsis site (13) The WhSC says that [E] surfaces in the same Spec,CP2 C 2° TP En root CP-layer as the WH-phrase. Accordingly, emb Spec,CP1 C 1° CP2 clausal ellipsis in English and Dutch will have root Spec,CP1 or Spec,CP2 C1° or C2° CP2 or TP Du different properties. All this is schematically emb Spec,CP1 or Spec,CP2 C1° or C2° CP2 or TP represented in table (13). The movement operation preceding ellipsis in FAs, i.e. left-peripheral focus fronting, targets Spec, CP2 (cf. Culicover 1991; Authier 1992; den Dikken 2003; van Craenenbroeck 2004). A phrase in Spec,CP2 survives TP-ellipsis, but not CP2-ellipsis. As the ellipsis site in English embedded clauses is CP2, non-WH-remnants (i.e. FAs) in this context should be ill-formed. In root clauses and in Dutch, the clausal ellipsis site is (or can be) TP. Here, non-WH-remnants are predicted to be grammatical. Hence, the WhSC makes the correct predictions regarding the embeddability of FAs (and sluicing) in Dutch and English. References AUTHIER, J.-M. (1992), 'Iterative CPs and embedded topicalization.' LI 23. • BARBIERS, S. (2002), 'Remnant stranding and the theory of movement.' In Alexiadou e.a. (eds.), Dimensions of movement. Benjamins. • CRAENENBROECK, J. van (2004), Ellipsis in Dutch dialects. LOT. • CRAENENBROECK, J. van & A. LIPTÁK (2006), 'The cross-linguistic syntax of sluicing.' Syntax 9. • CULICOVER, P.W. (1991), 'Topicalization, inversion, and complementizers in English.' In Delfitto e.a. (eds.), Going Romance and beyond. OTS. • DIKKEN, M. den (2003), 'On the morphosyntax of wh-movement.' In Boeckx & Grohmann (eds.), Multiple wh-fronting. Benjamins. • MERCHANT, J. (2004), 'Fragments and ellipsis.' L&P 27. • MERCHANT, J. (2008), 'Variable island repair under ellipsis.' In Johnson (ed.), Topics in ellipsis. CUP. • MORGAN, J.L. (1973), 'Sentence fragments.' In Kachru e.a. (eds.), Issues in linguistics. UIP. • ROSS, J.R. (1969), 'Guess who?' In Binnick e.a. (eds.), Papers from the 5th CLS.

© Copyright 2026