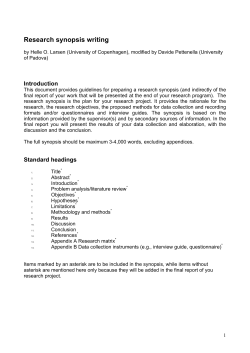

Communication and Collaboration USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-41. 2006. 689