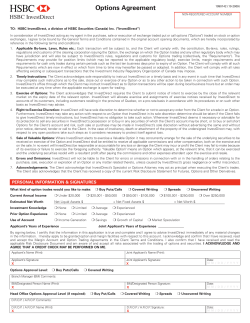

T r a p

Traps in Futures Thinking – and How to Overcome Them? By Dr. Mika Mannermaa Futures Studies Mannermaa Ltd., Finland Futures thinking – a merit list Despite the fact that systematic futures research is a phenomenon born and strengthened only after the Second World War, futures thinking has a long history. Actually it is as long as is the known history of human beings. How good are we in thinking of the future(s)? Here is an incomplete merit list of our competencies in this field: “Inventions have long since reached their limits, and I see no hope for further developments” -- Roman engineer Julius Sextus Frontinus, A.D. 10 “Heavier than air flying machines are impossible” -- Physicist Lord Kelvin, 1895 “1930 will be a splendid employment year” -- U.S. Department of Labor, 1929 “The Japanese don’t make anything the people in the U.S. would want” -- Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, 1954 “By the turn of this century, we will live in a paperless society” -- Roger Smith, chairman of General Motors, 1986 “I predict the Internet… will go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.” -- Bob Metcalfe, InfoWorld, 1995. The history of unsuccessful forecasts is a massive cornucopia offering a wide variety of juicy examples. Wallowing in them is, however, useless, if we do not learn from our mistakes. Our 1 abilities to think of the future credibly is limited by many factors, like inadequate basic data, knowledge and wisdom, bad methods or bad use of good ones, but also some specific traps of futures thinking. The most common of them are “This is it!” thinking, Paradigm blindness, Trendfaith, Cultural contempt, Over-enthusiasm and Disparagement of everything new. ”This is it!” When the Roman engineer Frontinus announced already 2000 years ago that everything, which there is to be invented, has been invented, he fell into the trap of ”This is it!” thinking so familiar to us all. It is tempting to think that some technological or other development has come to the end of its path, and “nothing new under the sun” is left to be expected. The collapse of the biggest societal experiment in the world history from 1989 was a surprise to all. During the decades of the Cold War after the Second World War people learnt to think that the existing status quo in world politics would be forever. Not a single futures researcher, political scientist, historian, politician or business leader made a protest, when the leader (or dictator, if you wish) of the German Democratic Republic, Erich Honecher, announced in the beginning of 1989 that the Berlin Wall would stay upright for at least the next hundred years. It doesn’t help much, if you in parenthesis in a subordinate clause in one of your six scenarios wrote that ”something like this might happen.” But nobody made a clear statement, with a loud voice, that ”Hey guys, listen to me, from 1989 the socialist block will start collapsing!””This is it!”, when it came to the global political status quo. But then the world changed. The collapse of the socialist block was interpreted by the well-known societal philosopher Francis Fukuyama so that it was the end result of the evolutionary battle between the two great ideologies, the Western market liberalism and Socialism. Survival of the fittest meant that the Western view was the winner.1 In his own way Fukuyama, too, fell into the trap of ”This is it!” thinking. As it must have been obvious, Fukuyama’s theses were opposed by many. Perhaps the best-known is Harvard professor Samuel Huntington’s article in the journal Foreign Affairs.2 His main argument was that the great civilizations – Western Christianity, Orthodox world, Islam, Confucean philosophy (China), Japanese culture, Hinduism, African and Latin American cultures – are fundamentally different to the amount that the future is featured by tensions and conflicts between them. Issues related to cultures bypass economic factors in 2 importance, which at the moment operate as the most powerful actors globally. Encounters of cultures strengthen their inner cohesion and emphasize differencies between them. Ideas of a single common world culture, meaning the dominance of the Western thinking or a birth of a new culture as a result of some sort of melting process of the present cultures, on the other hand, are implausible. The World Futures Studies Federation arranged a world conference on the theme Coherence and Chaos in Our Uncommon Futures – Visions, Means, Actions in 1993. 3 ”Uncommon” referred both to the unknown nature of the future and to the varied concepts of reality expressed by the different cultures, which are strange to each others. Different interpretations and educated guesses about these questions were presented in the conference, but eg. the idea of a global uniform culture was commonly considered both as implausible and undesirable. Democracy – or in more general terms: how taking care of societal affairs and decision-making concerning them should be arranged in the future – is an obvious example of ”This is it!” thinking, too. Political parties, regular elections, parliaments, governments, presidents, etc. These systems’ rituals continue to take place in an unchanging manner seemingly forever. That is, so we think. Most people never even start thinking of questioning whether things could be differently, some others are denying the whole discussion. People do not only think that our model of democracy has come to the end of its development – ”This is it!” – but many think that it is politically unacceptable to question the present model of democracy. Futures researchers have repeated some general slogans about the strengthening of “direct democracy”, but concrete models of how eg. decision-making at the levels of states and global community should be organized in the future are vague, to say the least. Although there are severe shortcomings in our models of democracy, and the potentials of information and communication technologies, real-time voting and virtual governance are mostly unused, democracy is a taboo. One is not allowed to discuss its weaknesses. But, believe me: ”This is NOT it!” Paradigm blindness The claim of the famous physicist lord Kelvin that flying machines, which are heavier than the air, like aircrafts, are impossible, represented a mode of thinking, which might be called paradigm blindness. Thomas Kuhn presented his well-known concept of paradigm originally in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in the beginning of the 1960’s.4 The word paradigm comes from 3 the Greek word paradeigma, which means a mode or pattern of thought. To Plato paradeigma meant the real world of ideas, of which the visible world is only a reflection. Kuhnian concept of paradigm is related to scientific problem-solving, which becomes a guiding thought-model in a certain discipline, and which creates a new research tradition (eg. Darwin’s theory of evolution or Einstein’s theories of relativity). The idea of scientific revolutions used by Kuhn has to do with paradigm shifts: For example Einstein gave birth to a revolutionary paradigm shift with his theories of relativity. In between paradigm shifts there exists, according to Kuhn, a period of “normal science”. During those periods the scientific activities stick to the predominant paradigm. 5 Experts in a discipline learn the existing wisdom, paradigm or doctrine telling them, what is the predominant way of thinking accepted by the scientific community in the field at a specific time. How do you make science, what are the accepted methods, what kind of empirical data is to be used, what is the nature of the results, what are the dominating results now, into what direction new research should be directed and how the students should be guided, which are the leading journals, and who are the biggest gurus. The idea of paradigms can be generalized outside of the domain of science, too. Similar pressure to stick to one’s own paradigm concerns industrial leaders, who have run their factories for 30 years, city mayors with same life and work experiences, members of all informal “jolly good fellows” networks, like freemasons, rotary clubs, feminist groups, religious sects, factories for raising ‘political broilers’ for parties and other clubs for elevating the spirit and feeling of togetherness among their members. Common education, work career, sources of information, industrial or other branch, shared experiences, the desire to look for the company of the people alike also outside office hours (motorcycling, playing golf, sailing, skiing, etc.) are all promoting the development of paradigmatic “we belong together” communities. This phenomenon can also limit our thinking and prevent us from seeing essential factors outside of our paradigm. The pressure to think in a similar way with our fellowmen and women, and pure paradigm blindness is lurking us all constantly and everywhere. Paradigm blindness is common in futures thinking, too. No wonder that one experienced airplane engineer forecasted in the 1930’s that the speed of a passenger aircraft in 1980 would be some 180200 kilometers per hour. In reality, already in 1965 one was able to build a supersonic airplane, the speed of which was multiple compared to the forecast of the engineer. The engineer was a member 4 of the “propeller paradigm community”. When making his predicition, he probably thought of how much you can increase the rolling speed of the propeller, how the aerodynamic properties of the planes can be improved, etc. In the beginning of the 1960’s, however, a new technological paradigm, aircrafts using jet engines, had been developed. The engineer of the 1930’s was not an expert of the new paradigm, and he was unable to take into account the possibilities of the new technology outside his domain of competence. Marshall McLuhan once thought that “We don’t know who discovered water, but we are pretty sure it wasn’t a fish." Every now and then it makes sense to take some distance from your normal paradigm in order to see better – and further. It may pay off to make a visit eg. to the seminars, meetings and web pages of “others” – even “enemies”. One may get good ideas and new perspectives even to familiar issues. Trend-faith In 1929, just before the Great Depression, when announcing that the next year will be a great year for employment (implying good prospectives for the economy in general, too) the U.S. Department of Employment made a gross forecasting mistake by leaning on trend-faith. Believing in trends is a natural and typically human way to think of development and future. If an object of observation has changed according to a certain pattern – eg. followed linear or exponential growth, cyclical fluctuations or some combination of them – people easily think that the same pattern will hold true in the future, too. For example econometric models using several variables, parameters and equations, express this message in a more complicated way than straightforward trendextrapolations, but basically the question is about the same thing: continuing the pattern of change discovered in the past into the future. Unchangeability must be included in these patterns, too. If some thing has not changed in the past, and you believe that it will not change in the future either, you apply one special case of trend-thinking. Basic postulates in trend-faith are thus unchanging change and unchanging unchange. One important expression of unchanging change is the idea of cyclical variations – seasonal fluctuations or long-waves (Kondratieff). These variations are identified from the past data, and it is thought that they will continue to exist in the same way also in the future. At least implicitly, several ceteris paribus assumptions are made. It is thought that factors, which are outside of the research topic, like 5 environmental issues, values, global factors or technologies in economic forecasts do not produce surprises: their impacts remain the same as they were in the past. Another way to put this is to say that in trend-thinking you believe that the structures do not change. Structural changes or breaks are clearly outside the reach of trend-thinking. One version of trend-faith is the so called railway thinking. It has been applied ao. in the home country of the author of this article, at least in politics in the 1970’s. The easiest and cheapest way to see the future of Finland was thought to be making a trip to Sweden. After coming back to Finland one could tell the laymen, what is the future of Finland after ten years. At that time it was considered that nations are like trains following each other on the same tracks. Some nations were further in their development, but all of them were supposed to follow the same path. And the “big brother” of Finland, Sweden, was ten years ahead. A modification of railway thinking called the model of flying goose was adopted in Japan after the World War Two. According to it the societies are following each other on the same development path, but those late-comers come closer and closer to the leading ones. The Japanese were cleverly applying the “second best” strategy, copying technologies developed in the leading-edge countries, and finally became number ones in some branches and innovations. For example in the 1960’s many societally important trends in the Western countries were ”wellbehaving” in the circumstances of strong economic growth. At that time trend forecasts didn’t fail always, at least not in the short-run. Since that period the economic environment has been more turbulent, and at the moment the credibility of economic trend predictions becomes close to zero, if the forecasting perspective is longer than a few months. Let’s take an empirical example from Finland. Professor in Economics Jaakko Pehkonen made an empirical study on aptness of the economic forecasts.6 In Finland in the Spring of 1996 forecasts on the growth of gross national product made by different economic research institutions for the year 1997 varied from 2,5 to 3,5 percent per year. Afterwards, it was discovered that the real growth in 1997 was 6,3%. Even the forecasts published in the Spring of 1997 were between four and five percent for that year, which was already passing by. Sometimes the forecasts have been somewhat more successful, but a cool-headed conclusion, however, is that it is primarily an accident, if an economic prediction hits even close to the target, even though the forecasting perspective would be only six months or so. 6 As all trend forecasts, econometric models are especially incapable of anticipating quick seasonal turns, and even more so, when it comes to structural changes. Actually, if the market economy operated effectively, a forecast, which includes a known turn in seasonal cycles, would be internally contradictory. Simplifying a bit: it is a self-destructive prophecy. From the point of view of futures research, in principle, bigger structural changes and breaks in economy, society and technology could be tackled by non-linear chaos mathematics. So far, however, it has been able to produce mainly theoretical results and simulations. It should be noted that the biggest problem related to the economic trend forecasts has not to do with the model makers and forecasters. They are usually well aware of the limitations and weaknesses of the models as well as of their intuitive and speculative assumptions. The problems are those economic actors, who uncritically believe in the forecasts produced by the models. Economic forecasts are, however, necessary even though you should not believe in them! The reason is that they express the self-understanding of the economy at a specific point of time. It is important, but instead of the forecasts themselves one should focus her attention to the assumptions behind the models. Nowadays, trend-thinking can be used for producing kind of reference scenarios, business as usual descriptions of the future. After producing them, one can start constructing the truly interesting alternative scenarios. Cultural contempt U.S. Secretary of State John F. Dulles expressed cultural contempt, when announcing in the 1950’s that the Japanese will never make anything, which the Americans would like to have. As we know, he was totally wrong. During the last decades, Japanese high-tech products from Panasonic, Sony, Toyota, Nissan, etc. have conquered the world of the American consumers. Generalizing somewhat, it seems so that the danger of falling into the trap of cultural contempt is directly related to the past success of the actor in question, like a government, national culture, a dominating company, even a single person: “We are so good that we don’t need to try!” Correspondingly, sensitivity to one’s own vulnerability seems to be inversely related to the issue of 7 how great future it used to have in the past. The hungriest for change and development are usually those, who have not yet reached success – in economy, politics, culture, science, sports, etc. Perhaps it wasn’t an accident that the losers of the Second World War – Japan, Germany, Finland – created the best economic success stories after the war. In economy, the trap of cultural contempt can go off in a situation, which Harvard professor Michael Porter has called a phase of wealth-centered economy. 7 In that phase the growth of economy is based primarily on the prosperity created earlier. It is tried to be maintained by purchases of companies and mergers, not by investments into production capital and by innovations. One chases for quick profits, and industrial activities with their entrepreneural risks are left to the background. Companies and other economic and societal actors are trying to hold on to the positions achieved in the past, competitiveness is weakening, motivations among the business leaders and employees are lowering and salaries are rising more rapidly than productivity. The economy drifts into a state of under-investments and scarce innovations. In the international competition those companies possessing real competitive advantages make successes and buy companies from countries having a wealth-centered economy. Actually a wealth-centered economy is the beginning of national decline. If a society is staring into the past and sticks to the benefits achieved earlier and does not create anything new, it cannot maintain its prosperity in the long-run. Philosophy of wealth-centered economy and cultural contempt among the leading economic and political actors is a destructive combination. An important question is, whether it is even in principle possible for national economies, sectors, clusters or companies, which have matured into wealth-centered economic phase to ”take a step or two backwards,” ie. to recreate investments and innovations. Mature companies and branches as well as other mature organizations like political parties, labor unions and administrative bodies of the Industrial Age are usually able to carry through only cosmetic changes in their strategies and operative actions, and very often it is not enough. What is needed, could be called ‘chaos’. New society is created by new organizing principles and actors. Multimedia software and applications are not produced in refrigerator factories or paper mills. Free market economy, at least in theory, takes care that the companies falling into the thinking trap of cultural contempt and rigidity (wealth-centerd economy) face serious troubles in confronting the future. Societal organizations are able to live longer “over their age” than economic ones. That is the basic reason, why we still have eg. political parties born from the tensions of a primitive industrial society even 8 though we live in an Information society. Naturally, this situation cannot last forever, and we will see new societal actors, solutions, models of democracy, etc. in the future. Sometimes we come to a situation, where we have to conclude that a barn is a barn, and it does not turn into a skyscraper, no matter how much colour we paint on it. If we don’t realize it, and stick to the thinking trap of cultural contempt, someone else will take care of the job of structural change for us. Over-enthusiasm and disparagement of everything new If Roger Smith and many other prophets of the 1980’s had been right, we should not have any papers on our desks, in our briefcases, seminar halls, offices or elsewhere in the society. On the other hand, according to Bob Metcalfe, who still acts as a big ICT guru eg. in the MIT’s Technology Review, there should be no Internet after 1996. Smith and Metcalfe failed badly, but due to different reasons. Over-enthusiasm and disparagement of everything new as attitudes towards the future represent the same false thinking-pattern, exaggeration, but, however, the opposite extremes of it. When a new technological or other development is in its embryonic phase, especially, if it is understood as being something promising, it is easily hoped and believed to come true more rapidly than what will be the case in reality. Paperless office is a good example. Expert systems based on artificial intelligence are other ones. There was much expectations concerning the development of these systems in the 1980’s, but still we are waiting for the clever virtual assistans to come. They will substitute virtual lawyers, doctors, engineers, etc. for the human ones. The possibilities of expert systems are huge, and they will come into our use some day in the future, even though the speed of development has not been quite as high as the most eager optimists thought some twenty years ago. And we do work more and more virtually, using less paper in the future, too. Opposite to over-enthusiam is disparagement of everything new, of which Metcalfe made himself guilty. It happened during a time, when the Internet thanks to the new world wide web technology had just started to spread out from the academic world to other spheres of society. 9 In addition to pure technological problems both over-enthusiam and disparagement of everything new are related to the problematique of how to identify, out of the new possibilities offered by technological development, those ones, which satisfy our real needs in the long-run, as private consumers, business leaders, experts, in our hobbies, etc. Which technological – and in principle, economic or societal – innovations will become parts of our consumer and other behaviour patterns, improving our life-quality, increasing the effectiveness of our work and making our businesses successful, which will only be passing fads, if even that much. For example, mobile phone is an innovation, which indisputably has been useful for us and increased our feelings of comfort. In only a little more than ten years it has changed our everyday life and work so deeply that it makes sense to speak of a clear cultural change. The key word here is attainability. Our employer, colleagues, family – everyone – assume that we can be reached by mobile phone all the time. If we insist not to be involved in this new culture, we will become disabled as workers, and ‘odd fellows’ as members of a family or in a tribe around some hobby. E-mail and Internet have reached a similar status. Accordingly, it is pretty safe to evaluate that those technological innovations, which essentially promote mobile culture (no wires anywhere in the future!) by making communication between people easier, more effective and user-friendly, will be successes in the future. This means ao. breakthrough of fusion technologies: In the future we will have a computer, net, e-mail, tv, dvd player, fax, printer, radio, video camera, genetic passport, drivers licence, etc. in a single wireless device. As important as it is to identify those technological and other ’weak signals’, which satisfy our real needs in the long-run, as important it is to understand, which of the many offerings of technologies and salesmen do not fall into that important category. Who still remembers tamagotchis? The wisdom of hindsight is sweet – but not everything went wrong Above some traps in futures thinking into which it is easy to fall were presented. The description was not exhaustive. As examples of other thinking problems, into which, however, we will not dive more deeply in this article, the following can be mentioned:8 10 An estimate of the future (possibly a forecast) has an impact on the real development and on itself in a self-fulfilling or self-destroying way. It is very difficult in advance to evaluate these kind of consequential influences as well as impacts of second, third, etc. degrees and the significance of feedback loops – future happenings have impacts on the new statements of the future. The future is not made only by prime ministers and business leaders but by housewives and by others, too. Putting together all the possible actions of the potential futures actors creates a mass of futures alternatives, which is impossible to totally ‘govern’ by any means available. Subjectivity, even total irrationality, in addition to all rational planning has its impact on how the future realizes itself, no matter whether we like it or not. There exist feelings, selfcensorship, lying, religious and ethnic fanaticism in economy, politics, and culture. Terrorists are there, shaping the future, independently of how lunatic we consider this phenomenon to be. There is no rational way to mentally control irrationality. Even the most “objective” researcher possesses many indirect, even unconscious, values and hypotheses in her/his studies. One can never get rid of them totally, and one should make the adopted values as explicit as possible. Data is always inadequate. We should remember, what Karl Popper wrote about future inventions: they cannot be known in advance. The same is inevitably valid, when it comes to their consequencies. Many research technicalities are related to the empirical data. With a large empirical survey we may achieve some generality, but surveys are superficial. Making some in-depth interviews helps us reach deeper understanding, but the problem is in generalizing it. And, no matter what is the nature of the empirical data, it is always restricted. As we all know, evaluation on how good a statement of the future (not necessarily a forecast) is in relation to the real development can only be made afterwards, a posteriori. It may take decades before we can consider, whether a statement of the future was good or not. People love to practice hindsight of wisdom, because we are so good in it. The rapid spread of the Internet in the 1990’s was not clearly foreseen either. Marshall McLuhan described the birth of a global village already decades earlier and Buckminster Fuller built his network-like models already in the 1960’s, but neither of them could predict that approximately 11 starting in the early 1990’s and thanks to the www technology the true global village would really start to develop itself in the form of the Internet. Due to the traps in futures thinking and other reasons, estimating happenings in the future has often been quite unsuccessful. Everything, however, didn’t go wrong. At best futures studies have shown convincing long-term perspectives and probably had impacts on the societal development processes. Futures researchers can also take some credit for self-torturing themselves pretty adequately on the failures in the field, in conferences, articles and books. We keep constantly saying that the future is unpredictable and that it should be thought of as alternatives only. We can construct an amount of n scenarios based on varying key assumptions, but we know that the one, which realizes itself into the present reality at some point of time in the future is # n+1. Practically always. Why, then, spend time and money for this seemingly useless effort to understand the future? My answer is that by thinking of those n possibilities you will become better prepared to the unknown, truly realizing one, too. And one thing is certain: the future materializes itself into the present somehow. During the past decades there has existed scepticism towards futures studies even among the experts. We have always been able to present numerous rational arguments for practising futures research. For example, thinking of the future systematically gives you evidently a better basis for making important decisions at present than drifting into the future without a faintest idea of alternatives, threats and possibilities offered by it. Still, during the over twenty years, which I have spent in the field, I have probably experienced at least 50 identity crises: “Is this something real, after all?” Even in futures studies accumulation of knowledge and understanding may be real, even though we cannot know the essential facts of the future.9 If you have read hundreds of reports, articles and books of the future, and made them yourself, too, you should have learnt something, both methodologically and substantially. You ought to have a broader perspective and deeper understanding of what might be essential in the future than eg. a business leader or an engineer, who both have their involvements elsewhere. After practicing his profession for 20 years, a carpenter is justifiably proud of his professional skills and experience. Why don’t we, are we somehow more stupid, unable to learn or something? 12 There are fortunately examples of phenomena, which were spoken among the futures researchers long before public political, economic and other debate started – and actions were taken, too. In the following, two examples are shortly described. One of the best examples is related to the relations between human activities and the nature (which we usually call the environment due to our self-centered attitudes), and the limitations of these relations. One of the pioneers in the field, Bob Jungk, published his book Tomorrow is already here already in the 1950’s. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring came out in 1962 and the research team in the MIT led by Dennis Meadows published their work Limits to Growth in 1972. The problematic relationships of our economic, societal and technological systems to the natural ecosystems were tackled from different angles in these works as well as in other discussions, meetings and writings of future-oriented researchers and activists. It was not until the United Nations’ Commission of Environment and Development (the so-called Brundtland Commission) published its report Our Common Future in 1987, when the establishments (governments) in many countries really started to take these extremely serious questions into their agendas. Our Common Future started a boom of ecologically sustainable development. Actually, the concept has become so popular that it is nowadays used not only related to ecological issues, but people speak improperly also of economic, social and cultural sustainability. Another good example is the information society. In the technologically most advanced countries – like the Nordic countries and the USA – the idea of the information society did not struck the establishment, political discussion and media until in the 1990’s. The European Union started a project called eEurope, and in my own country, Finland, strategies, programs and projects for advancing the information society in all societal spheres and at all levels were plenty at those days. Japanese professor Yoneji Masuda, however, started to use the concept of the information society already in the 1970’s. It was widely discussed among futurists and other researchers in the early 1980’s, ie. long before it really started to ‘catch fire’ in the public at large. An amusing feature in this discussion was that it took some years before the information society was understood deeply as a big societal development phase, comparable to the agrararian and industial societies. At first, the information society was understood technically, not societally. It meant mainly more computers, mobile phones and net connections and other technical devices to schools, workplaces, etc. The idea that information society brings with it true societal changes, like conflicts of interests, power struggles, ‘powershifts’, if we use Toffler’s terminology, etc. came only later. Now it is pretty widely known that more information does not mean less value conflicts. The earlier future-oriented 13 discussion probably had an impact on the present eagerness related to the idea of information society. At this point it should be remembered that the only purpose for presenting statements of the future is not to make self-fulfilling prophecies. The other important motivation is to construct futures prospects in order to start processes, which prevent those prospects from coming true. There might be other motivations, too, like an attempt to mess up things. It is extremely problematic and often practically impossible to measure the influences of futures statements on the real development. For example, it is very difficult to say, what was the impact of the theories of one of the most influential futures researchers of all times, Karl Marx, on the societal courses of events during the last 150 years or so. How much his theory on impoverishment of the labor class effected in the birth of the labor movement and in the birth of the Nordic welfare societies? What if he had never presented his theory publicly? This question belongs to the domain of contrafactual study of history. What about his theory on the accumulation of capital? At least we are witnessing it to happen every day during these days – just think of the mergers of the global giant companies in the field of media or the role of Microsoft.10 Conclusion: How to overcome traps in futures thinking A Quick guide for avoiding traps in futures thinking: ”This is it!”: Simply don’t ever think like this! Evolution on the globe has no end station, at least not as long as the sun keeps on heating us. Even though in the cultural evolution we are able to destroy much of our environment, cause the extinction of thousands of species, fight against each other, etc., still we are probably not able to destroy all the life on the earth. When thinking of the minor issues, like global economy or ideologies, development is going to continue generations from our times. Paradigm blindness. Take care that you don’t read only journals, magazines and web pages of your own discipline. In scenario and strategy groups, use as multivaried expertize as possible. Visit the domains of the ‘strangers’. If you are a business director, do something stupid: take part in a 14 seminar of a feminist activist group, go to a Britney Spears’ concert, read some Charles Bukowsky. Every now and then: avoid your colleagues, don’t take part in futures studies conferences only… Trend-faith. Don’t ask, whether an important trend is going to break down. Ask, when the breakdown will take place! You can start by making a list of trends, of which you think that they have been ‘well-behaving’ during the let say last 30 years. If you are able to name any such trend, keep on asking yourself, do you believe that it is going to behave well in the future, too. For how long? And based on what assumptions? If you after this process still believe in the continuation of this trend, be sure that you make some checking after half a year or so. Cultural contempt. Is your company overwhelmingly superior compared to all the competitors, are you the greatest and most successful, are you happy, yes or no? If yes, start thinking quickly! Others are not that bad. If you fall into your self-satisfied sleep, the others will be awake and lurk behind your back. They are greedy for success, which they haven’t experienced yet. Sergei Bubka wan seven World Championships in pole vault between 1983 and 1997. Was the first Championship in 1983 the reason for winning the rest six ones, or did he do some work for them? Over-enthusiasm and disparagement of everything new. Everyone, who has spent some time in a work community, can probably name some overly enthusiastic persons eager to grasp to any exciting idea, as well as persons, who seem to have adopted as their life mission an attitude, which says that you have to disparage every new idea presented by someone, especially, if the idea somehow differs from the normal way of thinking. Actually, both of these extreme attitudes may be valuable in eg. a strategic scenario project in a company, if you take care that neither of them starts to dominate the thinking of the scenario group. A group consisting only of neutral well-behaving bureaucrats will probably not produce anything interesting. In every organization trying to avoid traps in futures thinking and being thirsty for success, whether operating in business, administration, education or in the academy, it would be good to have a kind of disturbance generator (DG) to keep you awake in front of the turbulent future(s). The tasks of a DG include asking odd questions concerning the basic assumptions and modes of operation in the organization from the futures perspectives, identifying new important weak signals in the operating environment – in the economy, technology, world politics, societal issues, environment, values etc. 15 – having potential impacts on the organization’s development, and producing innovations related to products, services, customers, modes of operation, strategies and scenarios. A DG can be a person, a propeller head hanging around and reporting on interesting phenomena to the top leaders. It a can also be formed of regularly organized futures studios at the top level of the organization in question. In some bigger companies a DG has been organized more systematically using eg. company’s Intranet system for collecting new megatrends, weak signals and other important futures phenomena. The system also applies tools for organizing and prioritizing these phenomena, and the results are being used in the systematic scenario and strategy work of the company (see the figure). Calendar (months) 3 6 9 12 15 Activities Top Mgmt output Scenario report Report -w.s., -megas Output Scenario report Report -w.s., -megas Process Forum Futures Studio Futures Studio InfraInfrastructure INTRA -toolbox INTRA -toolbox Constant monitoring Report -w.s., -megas Futures Studio INTRA -toolbox Report -w.s., -megas Futures Studio INTRA -toolbox Report -w.s., -megas Futures Studio INTRA -toolbox Weak signals Megatrends Figure. Monitoring system of weak signals and megatrends in a company It is important to understand, however, that a DG is not as much a business unit, person or procedure as it is a new culture in the organization. It represents shifts in cultural thinking: from trends to breaks, from past to future, from sleep to awareness, from hierarchies to networks, from 16 machines to organisms, from arrogance to sensitivity – and from unchange to change. “Long live the Disturbance Generators!” Literature Bell, Wendell (1997) Foundations of Futures Studies. Vol 1. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick. 365 p. Fukuyama, Francis (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. New York. Free Press. Godet, Michel (2001) Creating Futures. Scenario Planning as a Strategic Management Tool. Ecnomica, Paris. 269 s. Gordon, Theodore J. (1992) The Methods of Futures Research. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 522, July, 25-35 Huntington, Samuel P. (1993) The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs. Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 2249. Kuhn,Thomas S. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago Ill. University of Chicago Press. Chicago. Kuhn,Thomas S. (1979) Second Thoughts on Paradigms. In The Structure of Scientific Theories, ed. Frederick Suppe. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, London, pp. 459-499. Mannermaa, Mika (1986) Futures research and social decision-making. Alternative Futures as a case study. FUTURES, Vol. 18, Oct, pp. 658-670. Mannermaa, Mika (1991) In Search of An Evolutionary Paradigm for Futures Research. FUTURES, Vol. 23, May, pp. 349-372. Mannermaa, Mika (Ed. 1992) Linking Present Decisions to Long-Range Visions. Selection of Papers from the XI World Conference of the World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF). Budapest. Vols. I and II, 511 pages. Mannermaa, Mika (2000) Multidisciplinarity, Methodologies and Futures Studies. Futures Research Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 2, Summer 2000, pp. 5-20. Masini, Eleonora (1993) Why Futures studies? Grey Seal Books. London. Porter, Michael (1991) The Wealth of Nations (Kansakuntien kilpailuetu.) Otava, Keuruu. What’s up in Science (Tieteessä tapahtuu) 3/2002. 1 2 Fukuyama 1992. Huntington 1993. 17 3 Mannermaa - Inayatullah - Slaughter 1994. Kuhn 1962. 5 Margaret Masterman calculated that Kuhn had used the word paradigm in 22 different meanings in his influential book. So, the concept is apt to many interpretations, see Kuhn 1979, p. 459-460. 6 What’s up in Science 3/2002. 4 7 Porter 1991. Cf. Bell 1997, 243-246, Gordon 1992, 26, Masini 1993, 47-53, and Godet 2001, 20-31. 9 Something we do know. Eg. there exist true statements of the future. I can say: “In 2045 a hundred years have gone since the establishment of the United Nations.” There are also statements, which are true now and in the future, too: “In a certain algebra 1+1=2,” is true in 2004, but also in 2500. In principle, historical statements, when being true stories, are as true in 2100 as in 2004, but here we cannot be sure. We cannot go back and make empirical observations on, how eg. the Second World War really happened. Many of us have roughly similar understanding of those happenings, but there are differences, too. It has also been pointed out that the history has usually been written by the winners, and very often by males. We can be pretty sure that Saddam Hussein’s story of the Iraq War is quite different from George Bush’s view. Finally, natural laws, like gravity, should hold true in the future, too (even though we cannot be sure in the deepest sense). It makes it possible to predict for example the timing of solar eclipses hundreds of years before their happenings. But all these examples are pretty trivial, when it comes to our task as futures researchers to say something essential of the future(s). 10 Taking up Marx in this way should not be interpreted as giving support to the marxist parties in politics. On the other hand, Marx should not be condemned as guilty to all of the stupidities, in which the real socialism fell. In the similar way one should not consider the father of liberalism, Adam Smith, as responsible for all those stupidities, which the Bush’s regime is causing. 8 18

© Copyright 2026