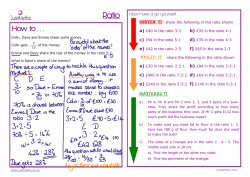

Getting started How to do more of it PART D ect