Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is Volume 20

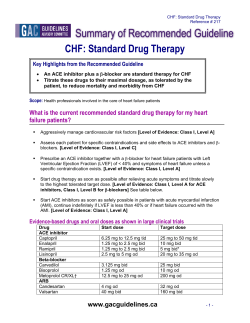

Volume 20 Number 2 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? SUMMARY • ACE inhibitors are the first-line choice when a renin-angiotensin system drug is indicated – ACE inhibitors have a more robust evidence base than angiotensin-II receptor antagonists (A2RAs) for all indications in terms of evidence for efficacy, safety and most patient factors. • A2RAs are an alternative to ACE inhibitors if a renin-angiotensin system drug is indicated but an ACE inhibitor cannot be used because of an intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough – The major benefit of A2RAs over ACE inhibitors is their lower rate of cough. However, cough may not be as common with ACE inhibitors as many health professionals perceive. The percentage of people reporting cough with ACE inhibitors in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) is about 10%, and as low as 2% in observational, real world studies. Discontinuation rates due to cough are lower than this. In the ONTARGET study, only 4.2% of patients in the ACE inhibitor group stopped treatment due to cough compared with 1.1% in the A2RA group. • Combination therapy with an A2RA plus an ACE inhibitor has a limited role and then only in certain indications • Based on this evidence, ACE inhibitors should comprise a higher proportion of reninangiotensin system drug prescribing than is currently the case – Across primary care in England, only about 70% of renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing is for ACE inhibitors at the current time, with 30% for A2RAs. However A2RAs account for 70% of the total spend on renin-angiotensin system drugs. – A review of prescribing in this area could improve quality of care and reduce prescribing costs. However, implementing changes to prescribing in this area is not straightforward, and a simple switch programme is not appropriate. Introduction Renin-angiotensin system drugs include ACE inhibitors, A2RAs (also called angiotensinreceptor blockers [ARBs]) and the new direct renin inhibitor, aliskiren▼ (which is licensed only for use in hypertension).1 ACE inhibitors and A2RAs are used in a wide range of indications including hypertension, heart failure, treatment post-myocardial infarction (MI), diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Prescribing can either be with an ACE inhibitor alone, an A2RA alone or, in some limited circumstances, combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor plus an A2RA. When choosing a renin-angiotensin system drug, as in any other therapeutic area, the decision should be guided by four factors: efficacy, safety, patient factors and cost (see Table 1 on page 2).2 The first priority is high quality prescribing, i.e. prescribing drugs with a robust evidence base. However, value for money is also important, as the NHS must make the most effective use it can of public money to deliver high-quality healthcare.3 This Bulletin is part of a suite of materials available on the renin-angiotensin system drugs floor of our e-learning website NPCi. If you want to test your understanding of the issues in this therapeutic area you can complete the related quiz before and after reading this Bulletin and compare your scores. For more details of the evidence in this area, see the reninangiotensin system drugs less than 60 minute workshop. This publication was correct at the time of preparation: March 2010 This MeReC Publication is produced by the NHS for the NHS MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 1 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? Table 1. Guiding choice in renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing based on effectiveness, safety, patient factors and cost2 EFFECTIVE SAFE No evidence that A2RAs are more effective than ACE inhibitors for any indication No evidence that A2RAs are safer than ACE inhibitors for any indication Concern that A2RAs may be less effective than ACE inhibitors in reducing some cardiovascular outcomes COST ACE inhibitors have a more robust evidence base than A2RAs for all indications PATIENT FACTORS Generic ACE inhibitors are less expensive than A2RAs A2RAs cause cough in fewer patients than ACE inhibitors (absolute difference in discontinuation due to cough 3% in ONTARGET) No difference in dosing regimens or monitoring requirements NB. The references to support these statements can be found in the text. Why are ACE inhibitors the first-line choice? effective than ACE inhibitors for any indication. There is robust evidence that ACE inhibitors reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality over placebo in hypertension,14 heart failure15 and stable ischaemic heart disease.16 The evidence that A2RAs reduce cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality over placebo in these indications is less clear (see Table 3 on page 3). However, when A2RAs have been compared with ACE inhibitors in heart failure20 and stable ischaemic heart disease,5 no differences in cardiovascular outcomes have been seen. ACE inhibitors are the first-line renin-angiotensin system drugs of choice for all indications (see Table 2). They have a more robust evidence base than A2RAs for all indications in terms of evidence for efficacy, safety and most patient factors (see Table 1). In all NICE guidance where renin-angiotensin system drugs are indicated, i.e. in hypertension,4 heart failure,7 post-MI,9 type 2 diabetes,10 type 1 diabetes11 and chronic kidney disease,12 ACE inhibitors are the first-line renin-angiotensin system drugs of choice. There are two general points to consider when comparing the evidence-base for ACE There is no evidence that A2RAs are more Table 2. Place in therapy of ACE inhibitors, A2RAs and combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor plus an A2RA in various indications ACE inhibitors A2RAs ACE inhibitor plus A2RA Hypertension First-line renin-angiotensin system drug4 If ACE inhibitor discontinued due to intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough4 and renin-angiotensin system drug in particular indicated No benefit, worse outcomes when compared with ACE inhibitor alone in ONTARGET5,6 Heart failure First-line renin-angiotensin system drug7 If ACE inhibitor discontinued due to intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough7 Possibly a specialist option after ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker optimised8 Requires careful monitoring of renal function Post-MI First-line renin-angiotensin system drug9 If ACE inhibitor discontinued due to intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough9 Not recommended in NICE postMI guidance9 Diabetes and CKD First-line renin-angiotensin system drug10–12 If ACE inhibitor discontinued due to intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough10–12 No benefit, worse outcomes when compared with ACE inhibitor alone in ONTARGET5,6 Full NICE CKD guidance says no evidence to suggest increased effectiveness over ACE inhibitor alone13 Requires careful monitoring of renal function if specialists are using in high-risk renal patients 2 MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? Table 3. Summary of evidence for ACE inhibitors and A2RAs vs. placebo for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality outcomes Indication ACE inhibitors vs. placebo A2RAs vs. placebo Hypertension • Reduced coronary heart disease (CHD) events, relative risk (RR) 0.83, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.8914 • No statistically significant reduction in CHD events, RR 0.86, 95%CI 0.53 to 1.4014 • No studies of A2RAs vs. placebo in stroke14 • Reduced strokes, RR 0.78, 95%CI 0.66 to 0.9214 Heart failure • Reduced all-cause mortality, odds ratio (OR) 0.80, 95%CI 0.74 to 0.8715 • Reduction in all-cause mortality of borderline statistical significance, OR 0.83, 95%CI 0.69 to 1.00 (P=0.048)17 • Reduced hospitalisations for heart failure, OR 0.64, 95%CI 0.53 to 0.7817 • Reduced hospitalisations for heart failure, OR 0.67, 95%CI 0.61 to 0.7415 Stable ischaemic heart disease • Reduced all-cause mortality, RR 0.87, 95%CI 0.81 to 0.9416 From one study TRANSCEND,18 • No statistically significant reduction in composite of CV death, MI, stroke or hospitalisation for heart failure, hazard ratio (HR) 0.92, 95%CI 0.81 to 1.0518 • Reduced non-fatal MI, RR 0.83, 95%CI 0.73 to 0.9416 • No significant reduction in all-cause mortality, HR 1.05, 95%CI 0.91 to 1.2218 • Reduced strokes, RR 0.78, 95%CI 0.63 to 0.9716 • No statistically significant reduction in MI, HR 0.79, 95%CI 0.62 to 1.0118 • No statistically significant reduction in stroke, HR 0.83, 95%CI 0.64 to 1.0618 Various indications • No statistically significant reduction in MI, OR 0.94, 95%CI 0.84 to 1.0619 — inhibitors and A2RAs. Firstly, A2RAs came to the market later than ACE inhibitors, therefore, many trials are versus active comparators not placebo. Secondly, as A2RA studies were generally conducted more recently than ACE inhibitor studies, greater use of other preventative drugs, such as statins, antiplatelets and beta-blockers, is a possibility. The “law of diminishing benefits” means that statistical benefit can become increasingly difficult to demonstrate with the addition of each preventative drug. The major benefit of A2RAs over ACE inhibitors is their lower rate of cough (but see below). There is no advantage with A2RAs over most ACE inhibitors in terms of dosing regimens or monitoring requirements.21 ACE inhibitors are considerably less expensive than A2RAs, as they are widely available generically. This could change in the future as patents begin to expire on A2RAs and generic forms become available (the first of which is likely to be losartan▼ in March 2010).22 However, it will probably be some years before several A2RAs become available at costs similar to the current costs of generic ACE inhibitors. What about cough? In all NICE guidance where renin-angiotensin system drugs are indicated, A2RAs are reserved for patients where a renin-angiotensin system drug is indicated, but an ACE inhibitor MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 has to be discontinued because of an intolerable ACE inhibitor-induced cough.4,7,9–12 The current NICE heart failure guidance states that ACE inhibitor-induced cough rarely requires treatment discontinuation.7 A cough may occur in a patient taking an ACE inhibitor for reasons other than as a side effect to this drug. Therefore, other possible causes should be considered before switching to an A2RA. In patients with heart failure, it might be a symptom of pulmonary oedema.7 How common is cough? Evidence from clinical studies suggests that cough may not be as common with ACE inhibitors as many health professionals perceive. The true rate of cough is difficult to quantify, but a systematic review of reninangiotensin system drugs in hypertension suggested the rate of cough with ACE inhibitors was about 10% from RCT data and 2% from observational data.23 The latter is probably closer to ‘real life’ with regard to the reporting of side effects. However, not all coughs (even if they are thought to be caused by the ACE inhibitor) require the drug to be stopped. In the ONTARGET study, a large RCT which included more than 25,000 patients at high cardiovascular risk but without heart failure, just 4.2% of patients stopped treatment due to cough with the ACE inhibitor, ramipril.5 ONTARGET had a run-in period, whereby included patients had already demonstrated tolerability to both telmisartan▼ and ramipril over a short period of time. This may have skewed the results in favour of tolerance to Cough may not be as common with ACE inhibitors as many health professionals perceive 3 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? Figure 1. Effect of A2RA treatment rather than ACE inhibitor treatment on risk of cough over 4.5 years for people at high cardiovascular risk (without heart failure)5 Imagine 100 people at high cardiovascular risk (without heart failure) taking an ACE inhibitor. In the next 4.5 years about 4 of them will stop treatment due to a cough, 96 of them will not stop treatment due to a cough (100 – 4 = 96). However, if those same 100 people each take an A2RA rather than an ACE inhibitor for 4.5 years: • About 3 people will be ‘saved’ from stopping treatment due to a cough (the yellow faces). • About 96 people will not stop treatment due to a cough — but would not have done so even if they had taken an ACE inhibitor (the green faces). • About 1 person will still stop treatment due to a cough even though they take an A2RA (the red faces). But remember • It is impossible to know for sure what will happen to each individual person. • All 100 people will have to take the A2RA rather than the ACE inhibitor for 4.5 years. These 96 people will not stop treatment due to a cough within 4.5 years whether they take an ACE inhibitor or an A2RA. These 3 people will be ‘saved’ from stopping treatment due to a cough within 4.5 years because they take an A2RA instead of an ACE inhibitor. This 1 person will stop treatment due to a cough within 4.5 years whether they take an ACE inhibitor or an A2RA. The image has been produced using Dr Chris Cates’ software VisualRx 3.0. More information can be obtained from the website www.nntonline.net some extent, but other studies have found similar rates, and this large trial in a wide ranging population of patients still provides valuable evidence for the rate of cough with ACE inhibitors compared with A2RAs. 4 Cough is common in patients with heart failure, many of whom have smoking-related lung disease.7 However, the proportions of patients who stopped treatment because of cough in the main heart failure trials which compared ACE inhibitors with A2RAs are similar to those in ONTARGET. Discontinuation due to cough in the ACE inhibitor groups in other studies ranged from 2.5% to 4.1%.24–26 due to cough compared with 1.1% in the A2RA (telmisartan) group.5 This is an absolute difference of just 3.1% and indicates a number needed to harm (NNH) with ramipril of 32 over 56 months. This means 32 people need to be treated with telmisartan rather than ramipril for four and a half years to prevent one person having to stop treatment because of cough. Put another way, if 100 people like those in ONTARGET all took telmisartan rather than ramipril for four and a half years, only three of them would avoid discontinuation due to cough, and one person would still have to discontinue treatment because of cough. Figure 1 gives a pictorial representation of these figures. How much less common is cough with A2RAs? In ONTARGET, 4.2% of patients in the ACE inhibitor (ramipril) group stopped treatment Although, like the ACE inhibitor, the A2RA was well tolerated in ONTARGET, it was not without side effects. A significantly greater number of patients discontinued telmisartan than MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? ramipril because of hypotension (telmisartan 2.7% vs. ramipril 1.7%, NNH with telmisartan 100). In contrast, significantly fewer patients discontinued treatment because of angioedema (telmisartan 0.1% vs. ramipril 0.3%, NNH with ramipril 500).5 Why does combination therapy with an A2RA plus an ACE inhibitor have a limited role? Combination therapy is based on the theory that an A2RA plus an ACE inhibitor blocks the renin-angiotensin system more completely than either drug alone, possibly benefiting patients with hypertension, kidney disease and heart failure. However, it is important to consider what type of evidence there is for combination therapy. Is prescribing based on surrogate, disease-oriented outcomes (DOOs), such as blood pressure or albuminuria reduction or, more appropriately, on clinical patient-oriented outcomes (POOs), such as cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and the development of end-stage renal disease? The clinical outcome data from the ONTARGET study has started to change views on whether combination therapy has benefits for patients in terms of them living longer or better. ONTARGET One of the key findings from ONTARGET was that combination therapy with ramipril plus telmisartan was no more effective than ramipril alone, but was associated with significantly more discontinuations due to hypotension, syncope, diarrhoea and renal impairment.5 After a median of 56 months, there was no difference in the rates of the primary outcome (a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, MI, stroke or hospitalisation for heart failure) between any of the groups (16.5% with ramipril, 16.7% with telmisartan, and 16.3% with combination).5 The effects of combination therapy on renal outcomes are of particular concern as, rather than being beneficial, combination therapy actually worsened major renal outcomes.5,6 ONTARGET was not a study specifically in renal patients – patients with significant renal disease were excluded and most patients did not have nephropathy at baseline. However, it did have prespecified renal endpoints, most of which were adversely affected by combination therapy.6 Compared with ramipril alone, telmisartan plus ramipril significantly increased the primary renal outcome (a composite of any dialysis, doubling of serum creatinine and death) with a NNH of 91 over 56 months (HR 1.09, 95%CI 1.01 to 1.18); the secondary renal outcome (any dialysis or doubling of serum creatinine) with a NNH of 215, and the component renal endpoint of acute dialysis with a NNH of 562.6 Even in the subgroup of patients with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria at baseline, there was MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 no benefit from combination therapy on the primary renal outcome.6 What is the place, if any, of combination therapy for various indications? Table 2 on page 2, summarises the place of combination renin-angiotensin system drug therapy in various indications. In hypertension, the best evidence comes from ONTARGET, where 69% of patients had hypertension.5 As discussed above, there was no benefit with combination therapy in this trial in terms of cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, and there were more harms, with worse renal outcomes and more discontinuations compared with ramipril alone.5 In its post-MI guidance, NICE states that combining an ACE inhibitor with an A2RA is not recommended for routine use post-MI.9 The VALIANT study with captopril, valsartan▼ or both these drugs in patients with heart failure post-MI found combination therapy was no more effective than captopril alone and was associated with more adverse effects.26 The full CKD guidance from NICE states that there is no evidence to suggest increased effectiveness of combining an ACE inhibitor with an A2RA over and above the maximum recommended dose of each individual drug.13 A meta-analysis of 49 RCTs in patients with nephropathy found that combination therapy reduced proteinuria (a DOO) more than either drug alone, but whether this actually benefits patients is unclear.27 The trials in this metaanalysis were mainly small and short-term, and there were no data on clinical endpoints, or on long-term safety. In ONTARGET, combination therapy showed contrasting effects on renal DOOs.6 It had beneficial effects on proteinuria, but worsened glomerular filtration rate. Most importantly, however, ONTARGET found combination therapy led to worse not better major renal outcomes.5,6 Therefore, if specialists are using combination therapy in high-risk renal patients, this requires very careful patient monitoring. ONTARGET found combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor plus an A2RA was no more effective than an ACE inhibitor alone Combination therapy in ONTARGET worsened major renal outcomes Finally, in heart failure, combination therapy could be an option for a minority of patients.8 In 2003, when NICE heart failure guidance 7 was published, no firm recommendation on combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor plus an A2RA could be made, but this pre-dated the publication of the CHARM studies with candesartan.28 NICE heart failure guidance is due to be updated in August 2010 and the NICE website should be consulted for updates. Based mainly on CHARM-Added,29 heart failure guidance from SIGN recommends that patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction who are still symptomatic despite optimised ACE inhibitor and betablocker therapy may benefit from the addition of candesartan following specialist advice.8 5 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? Figure 2. Variation in renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing at practice level (by items: year to September 2009)32 30% Proportion of practices 25% 15% 10% 6 95-100 90-95 85-90 80-85 75-80 70-75 65-70 Proportion of ACE-inhibitors prescribed (% total renin-angiotensin system drug items) Combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor plus an A2RA has been shown to significantly reduce hospitalisations, but not mortality, in patients with heart failure compared to monotherapy with an ACE inhibitor.20 Hospitalisation is an important clinical endpoint for these patients, and a meta-analysis found that adding an A2RA to an ACE inhibitor avoids one hospitalisation for every 26 patients treated over one to three years.20 The trade off with this benefit is the greater risk of adverse effects with combination therapy. Adding an A2RA to an ACE inhibitor in people with heart failure increases the risk of worsening renal function, hyperkalaemia and hypotension.30 Therefore, careful patient monitoring is again paramount. to an A2RA. In uncomplicated hypertension, a renin-angiotensin system drug in particular may not necessarily be indicated and either a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker may be suitable.4 Looking at the data in England at practice level, in the year to September 2009, 11.5% of practices had ACE inhibitor prescribing rates of at least 80%, showing this level of prescribing is achievable (see Figure 2).32 However, most practices have levels lower than this, suggesting that improvements could be made. Data from the NHS Information Centre’s report on hospital prescribing33 suggest there is a statistically significant correlation between primary and secondary care in the proportion of renin-angiotensin system drugs prescribed as ACE inhibitors (based on cost). Figure 3 on page 7, shows SHAs with a higher proportion of ACE inhibitor prescribing in hospital also have a higher proportion in primary care, and vice versa.34 An integrated approach between primary and secondary care in the prescribing of renin-angiotensin system drugs would therefore seem to be a vital component of any approach to improve prescribing in this area. A Better Care Better Value indicator related to increasing low cost prescribing of drugs affecting the renin-angiotensin system was published in April 2009.3 What level of A2RA prescribing would seem appropriate from the evidence? An integrated approach between primary and secondary care is vital to improve prescribing in this area 60-65 55-60 50-55 45-50 40-45 35-40 30-35 25-30 0% 20-25 5% 15-20 It is reasonable to expect ACE inhibitors to make up at least 80% of renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing 20% Based on the evidence outlined above, the majority of renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing should be for ACE inhibitors. In 2006, the full hypertension guidance from NICE assumed (based on expert opinion) that 80% of patients starting on ACE inhibitors would continue with these,31 but this proportion of ACE inhibitor prescribing is higher than the current average. Currently, across primary care in England an average of about 70% of reninangiotensin system drug prescribing is for ACE inhibitors and 30% for A2RAs.32 However, A2RAs account for 70% of the total spend on renin-angiotensin system drugs.32 Given that the major benefit of A2RAs over ACE inhibitors is their lower rate of cough, and the percentage of people reporting cough with ACE inhibitors in RCTs is about 10%23 (and not all these people will require the drug to be stopped) it is reasonable to expect that at least 80% of reninangiotensin system drug prescribing should be for an ACE inhibitor. If an ACE inhibitor has to be discontinued in a patient because of cough, it may be that another class of antihypertensive could be considered before routinely switching What savings could be made if the proportion of ACE inhibitor prescribing was increased? The total cost of renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing in primary care in England is about £366 million per year (based on data to quarter March 09).32 This reflects approximately 70% of prescribing being for ACE inhibitors and 30% for A2RAs. If the prescribing of ACE inhibitors was increased to 80% (and A2RAs decreased to 20%), the total cost of renin-angiotensin system drugs per year would be about £298 million – a saving of about £68 million per year. MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? Primary care prescribing by SHA, % of net ingredient cost of renin-angiotensin system drugs which are ACE inhibitors Figure 3. Correlation between hospital and primary care renin-angiotensin system drug prescribing at SHA level (by net ingredient cost)33,34 45 40 R² = 0.7768 P = 0.0007 35 30 25 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 Hospital prescribing by SHA, % of net ingredient cost of renin-angiotensin system drugs which are ACE inhibitors R2 = correlation coefficient These figures are estimates, but they show that significant savings could be made by reviewing the prescribing of renin-angiotensin system drugs. However, implementing changes to prescribing in this area is not straightforward, and a simple switch programme is not appropriate. For new patients, the evidencebased position is that ACE inhibitors are the firstline renin-angiotensin system drug of choice in all indications. However, for patients already being treated with renin-angiotensin system drugs any changes need to be individualised, as this is a complex area in which to optimise the use of medicines. More information and materials on implementing better practice in this area can be found on the National Support Materials floor of the NPCi website. References 1. Aliskiren Summary of Product Characteristics. Accessed from www.emc.medicines.org.uk/ on 08/02/10 2. Barber N. What constitutes good prescribing? BMJ 1995;310:923–25 3. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement website. Accessed from www.productivity.nhs. uk/ on 08/02/10 4. NICE. Hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care. Clinical guideline 34. June 2006. Accessed from www. nice.org.uk/cg34 on 08/02/10 5. The ONTARGET investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547–59 6. Mann JFE, et al. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:547–53 7. NICE. Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. Clinical guideline 5. July 2003. Accessed from www.nice.org.uk/cg5 on 08/02/10 8. SIGN. Management of chronic heart failure. Guideline No. 95. February 2007. Accessed from www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/95/index.html MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2 on 08/02/10 9. NICE. Myocardial infarction: secondary prevention. Clinical guideline 48. May 2007. Accessed from www.nice.org.uk/cg48 on 08/02/10 10. NICE. Type 2 diabetes: the management of type 2 diabetes. Clinical guideline 87. May 2009. Accessed from www.nice.org.uk/cg87 on 08/02/10 11. NICE. Type 1 diabetes: diagnosis and management of type 1 diabetes in children, young people and adults. Clinical guideline 15. July 2004. Accessed from www.nice.org.uk/CG15 on 08/02/10 12. NICE. Chronic kidney disease: early identification and management of chronic kidney disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Clinical guideline 73. September 2008. Accessed from www.nice.org.uk/cg73 on 08/02/10 13. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Chronic kidney disease: national clinical guideline for early identification and management in adults in primary and secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, September 2008. Accessed from http://guidance. nice.org.uk/CG73/Guidance/pdf/English on 08/02/10 14. Law MR, et al. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular 7 Document Angiotensin-II Title receptor antagonists: what is the evidence for their place in therapy? disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ 2009;338:b1665 25. Dickstein K, et al. Effects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:752–60 15. Flather MD, et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. Lancet 2000;355:1575–81 26. Pfeffer MA, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1893–906 16. Baker WL, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II-receptor blockers for ischaemic heart disease. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:861–71 27. Kunz R, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of monotherapy and combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system on proteinuria in renal disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:30–48 17. Lee VC, et al. Meta-analysis: angiotensinreceptor blockers in chronic heart failure and high-risk acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:693–704 28. Pfeffer MA, et al. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 2003;362: 759–66 18. The TRANSCEND Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1174–83 29. McMurray JJV, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet 2003;362:767–71 30. Lakhdar R, et al. Safety and tolerability of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor versus the combination of angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Card Fail 2008;14:181–88 19. Volpe M, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: an updated analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Hypertens 2009;27:941–46 20. Shibata MC, et al. The effects of angiotensinreceptor blockers on mortality and morbidity in heart failure: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1397–402 31. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Hypertension: management in adults in primary care: pharmacological update. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2006. Accessed from http://guidance.nice.org.uk/index. jsp?action=download&o=30111 21. BNF 58, September 2009. Accessed from www. bnf.org on 08/02/10 22. UKMI patents database. Accessed from www.ukmicentral.nhs.uk/pressupp/pe.htm on 08/02/10 32. Personal communication. Prescription Services NHS Business Services Authority. October 2009 23. Matchar DB, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for treating essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:16–29 33. NHS Information Centre. Hospital Prescribing, 2008: England. October 2009. Accessed from www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/ primary-care/prescriptions/hospital-prescribing2008:-england on 08/02/10 24. Pitt B, et al. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial – the losartan heart failure survival study ELITE II. Lancet 2000;355:1582–87 34. Personal communication. Centre. January 2010 NHS Information The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is associated with MeReC Publications published by the NPC through a funding contract. This arrangement provides NICE with the ability to secure value for money in the use of NHS funds invested in its work and enables it to influence topic selection, methodology and dissemination practice. NICE considers the work of this organisation to be of value to the NHS in England and Wales and recommends that it be used to inform decisions on service organisation and delivery. This publication represents the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the Institute. NPC materials may be downloaded / copied freely by people employed by the NHS in England for purposes that support NHS activities in England. Any person not employed by the NHS, or who is working for the NHS outside England, who wishes to download / copy NPC materials for purposes other than their personal use should seek permission first from the NPC. Email: [email protected] Copyright 2010 National Prescribing Centre, Ground Floor, Building 2000, Vortex Court, Enterprise Way, Wavertree Technology Park, Liverpool, L13 1FB Tel: 0151 295 8691 Fax: 0151 220 4334 www.npc.co.uk www.npci.org.uk 8 MeReC Bulletin Volume 20, Number 2

© Copyright 2026