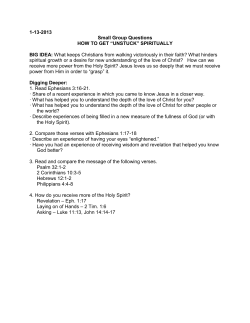

WHAT IS THE GOSPEL? J. B. Hixson, Ph.D. www.notbyworks.org