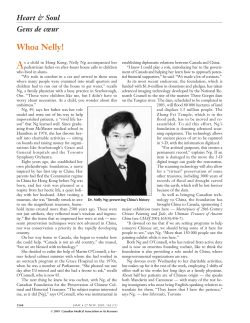

China’s Unassertive Rise: What Is Assertiveness and