What Is the Impact of the Internet on

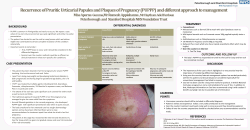

336 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 What Is the Impact of the Internet on Decision-Making in Pregnancy? A Global Study Briege M. Lagan, PhD, RM, Marlene Sinclair, PhD, RM, and W. George Kernohan, BSc, PhD ABSTRACT: Background: Women need access to evidence-based information to make informed choices in pregnancy. A search for health information is one of the major reasons that people worldwide access the Internet. Recent years have witnessed an increase in Internet usage by women seeking pregnancy-related information. The aim of this study was to build on previous quantitative studies to explore women’s experiences and perceptions of using the Internet for retrieving pregnancy-related information, and its influence on their decision-making processes. Methods: This global study drew on the interpretive qualitative traditions together with a theoretical model on information seeking, adapted to understand Internet use in pregnancy and its role in relation to decision-making. Thirteen asynchronous online focus groups across five countries were conducted with 92 women who had accessed the Internet for pregnancy-related information over a 3-month period. Data were readily transferred and analyzed deductively. Results: The overall analysis indicates that the Internet is having a visible impact on women’s decision making in regards to all aspects of their pregnancy. The key emergent theme was the great need for information. Four broad themes also emerged: ‘‘validate information,’’ ‘‘empowerment,’’ ‘‘share experiences,’’ and ‘‘assisted decision-making.’’ Women also reported how the Internet provided support, its negative and positive aspects, and as a source of accurate, timely information. Conclusion: Health professionals have a responsibility to acknowledge that women access the Internet for support and pregnancy-related information to assist in their decision-making. Health professionals must learn to work in partnership with women to guide them toward evidence-based websites and be prepared to discuss the ensuing information. (BIRTH 38:4 December 2011) Key words: decision-making, information seeking, Internet, online focus groups, pregnant women The ethical need for health professionals to respect autonomy and respond to consumer demands has resulted in extensive international interest to understand health care decision-making and strengthen ‘‘shared’’ decision-making within policy and practice developments (1–3). Decision-making is an integral component of maternity care and is supported globally by recommendations that reinforce the importance of informed choice for pregnant women (4–6). To make informed choices, women need access to evidencebased information. The Internet has the potential to offer consumers of health care an extensive mechanism and resource for information. Recent data indicate that the growth rate for Internet use in the past decade has increased by almost 500 percent, and 30 percent of the world’s population now has online network access (7). With almost 136 million websites currently disseminating pregnancy-related information, online usage by pregnant women is growing rapidly (8–10). A review of the literature demonstrated limited evidence exploring pregnant women’s use of the Internet as Briege M. Lagan is a Research Fellow, Marlene Sinclair is a Professor of Midwifery Research, and W. George Kernohan is a Professor of Health Research at the Institute of Nursing Research, University of Ulster, Jordanstown, United Kingdom. Address correspondence to Dr. Briege M. Lagan, PhD, RM, 11 Inishowen Park, Portstewart, County Londonderry BT55 7BQ, UK. This study was supported by a postgraduate studentship award from the Department for Employment and Learning, Belfast, United Kingdom. Accepted March 7, 2011 2011, Copyright the Authors Journal compilation 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 337 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 a source for health information (11). Findings were found within the text of papers investigating other issues, with the Internet only peripherally mentioned. The ability to seek and exchange Internet information depends both on having access to the medium and also necessary technical skills. It also calls for basic competence in being able to choose, classify, and critically evaluate the information that emerges. Information seeking is described as a holistic learning process to seek meaning (12). For health care practitioners and policy-makers to be able to identify and thus address the information needs of pregnant women, their dependence on the process and their experience within it must be clearly understood. This study builds on previous quantitative studies (10,13) that investigated pregnant women’s use of the Internet in pregnancy and the Internet’s effect on decisionmaking. Although quantified evidence can be powerful, it can fail to reveal understanding behind experiences. This study drew on the interpretive traditions within qualitative research to explore in-depth women’s experiences and perceptions of using the Internet for retrieval of pregnancy-related information, and the influence this medium had on their decision-making processes. Methods The conceptual design was underpinned by a theoretical model of information seeking adapted for the study. Kuhlthau’s (12) information-seeking process was modified to include work conducted by Kalbach (14) on seeking information on the Internet, and to integrate ‘‘decision-making’’ into the framework. Setting and Sampling As Lehoux et al pointed out, focus groups should be conceptualized as social spaces in which participants coconstruct the ‘‘patient’s view’’ by acquiring, sharing, and contesting knowledge (15). As a result of the diverse global location of the participants and the topic of study (i.e., ‘‘Internet users’’), it was considered that online would be the most appropriate setting for data collection. Turney and Pocknee also advised using virtual focus groups whenever the populations are difficult to recruit or access (16). The method of using moderated asynchronous online focus groups was chosen instead of the synchronous version primarily because managing the logistics of scheduling and time zones for both researcher and participants can be problematic. In addition, synchronous discussion requires participants to have higher levels of computer literacy (17). Asynchronous communication allowed the geographically separated participants to join the discussion at a time convenient to each. Participants were drawn from a population of 193 women who had participated in a web-based survey, used the Internet as a medium for information in pregnancy, and expressed a willingness to engage in an online focus group. Demographic details from a previous survey were used to stratify the focus groups by country of residence (13) (Table 1). Data Collection Thirteen asynchronous online focus group discussions across five countries were conducted over a 3-month Table 1. Composition of Focus Groups According to Country, Number Expressed Interest and Invited, Number Responded, and Number Participated Focus Group Australia 1 Australia 2 Australia 3 Australia 4 Canada New Zealand 1 New Zealand 2 United Kingdom 1 United Kingdom 2 United Kingdom 3 United Kingdom 4 United States 1 United States 2 Total No. of Participants Expressed Interest and Invited No. Responded to Invitation No. of Participants in Each Focus Group 15 15 15 15 15 14 14 15 15 15 15 15 15 193 5 10 9 7 7 4 7 10 7 8 8 8 11 108 5 9 6 7 7 4 7 9 7 7 7 6 11 92 338 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 period. The lead researcher (B. M. Lagan) e-mailed interested participants and set up individual listserve accounts for each of the focus groups, using an Internet service provider. Measures were taken to control access and protect anonymity. The groups were moderated by the researcher (B. M. Lagan), an experienced midwife trained in conducting asynchronous communication. According to Madge, actually seeing someone’s face can give participants a sense of reassurance (18). In an effort to develop rapport and a trusting relationship with the prospective participants, each group’s home page contained a brief profile of the researcher’s qualifications, her photo, the purpose of the study, and the name of the institution conducting it. Before data collection, the invited participants were provided with detailed instructions on how to access and interact in the online discussion forum and how to unsubscribe from the group if they wished to do so. Focus Group Guide The structure of the focus group guide was designed around the theoretical framework and the findings from two previous surveys on Internet use in pregnancy (10,13). Key areas of discussion included: what was the need to search the Internet; why it was used as an information source; how information was retrieved, appraised, and used; and whether it influenced women’s decisions about how their pregnancy should be managed. Within this loose framework, questioning was unstructured and open ended, which allowed the respondents to answer from a variety of viewpoints. Pilot Study A pilot study was undertaken before the main study to evaluate the interview guide and test the feasibility and effectiveness of using an online medium for qualitative data collection and to verify that the system worked in the actual user environment. After the pilot study, minor modifications were made to the focus group discussion guide. No technical issues were identified. Ethical Considerations Potential benefits of the study were deemed to outweigh any risks or inconveniences. Ethics applications were submitted to, and approval granted through, arrangements for research governance at the University of Ulster and the Office for Research Ethics Committees in Northern Ireland. All potential respondents were provided with a focus group protocol and participant information sheet containing detailed information about the study. A positive response to the e-mail invitation to participate in an online focus group discussion constituted consent. All participants were advised that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participation by ‘‘invite only’’ allowed the moderator to retain control of who had access and could contribute to the group. To protect participant’s identity and confidentiality, all data went through a de-identification process. Any participant who contributed to the discussion needed only to identify herself to the group by a username of her choice; thus, the participant could retain control over protecting her identity. To further preserve anonymity, pseudonyms have been used in the data presented in this paper. Data Analysis All text from each online focus group discussion was made anonymous, copied, and pasted verbatim into the qualitative data management tool, NVivo 7 (19). Analysis and data collection were conducted concurrently, commencing as soon as the first posting was entered using Ritchie and Spencer’s five-stage framework (20). Initially the lead researcher (B. M. Lagan) worked with the transcripts deductively, using the elements of the theoretical framework as a priori themes. She then worked more inductively with the data to identify comments on other didactic themes relating to women’s experiences and views on use of the Internet as an information source in pregnancy and the effect it had on their decisions about how their pregnancy should be managed. M. Sinclair and W. G. Kernohan read a subset of the texts to check the credibility and trustworthiness of the developing analysis. Feedback from the participants on the accuracy of the identified categories and themes was also sought. Some comments were selected to represent the breadth and depth of themes, and are reported verbatim. Results Quantitative data are reported in the first instance to provide a sense of the overall demographic profile of the focus groups. Of 193 women who initially expressed an interest to participate, 108 (56%) responded to the e-mail invitation, and of these 92 participated in a focus group. The average number of participants for each group was 7, ranging from 4 to 11 (Table 1). Table 2 presents the demographic profile of the participants, pregnancy data, and types of antenatal care. The central theme identified was a ‘‘need’’ for information, with four broad themes emerging repeatedly from the focus groups: ‘‘validate information,’’ ‘‘empowerment,’’ ‘‘share experiences,’’ and ‘‘assisted 339 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 Table 2. Demographic Profile of Online Focus Group Participants (n = 92) Characteristics Mean (SD) Range 29.9 (4.88) 19–39 Age (yr) Mean (SD) Marital status Married Single but in steady relationship Divorced Highest level of education completed Grammar ⁄ secondary ⁄ high school Technical college ⁄ diploma Undergraduate degree (Associate or Bachelors) Postgraduate degree Pregnancy status Pregnant Postnatal First pregnancy Yes No Pregnancy complications Yes No Type of antenatal care Midwife only Obstetric consultant only General Practitioner only Shared care* No antenatal care Internet access at home Yes No Formal Internet training Yes No Perception of Internet skills Expert Nonexpert 80 (87.0) 11 (12.0) 1 (1.1) 19 (20.7) 19 (20.7) 35 (38.0) Health professionals often don’t have the time or inclination to explain things in the detail you would like. (Leah, Australia) When women met with their doctor or midwife (less frequently than they would have liked), they viewed them as ‘‘busy people.’’ Some women described their appointments being ‘‘tick box’’ exercises for their health professionals ‘‘filling out irrelevant and outdated statistics on the maternity notes … rather than chatting about their pregnancy.’’ Others did not want to ‘‘bother’’ their health professionals unnecessarily: I felt my questions were too ‘‘small’’ for the doctor to answer, and just needed a little info, and felt there was no reason to bother her. (Noelle, Canada) 19 (20.7) 34 (37.0) 58 (63.0) 53 (57.6) 39 (42.4) 38 (41.3) 54 (58.7) 23 (25.0) 21 (22.8) 3 (3.3) 44 (47.8) 1 (1.1) 89 (96.7) 3 (3.3) 27 (29.3) 65 (70.7) The infrequency of antenatal visits and time constraints at appointments appeared to have an influence on Internet use to meet information needs between appointments: Face-to-face contact — for most of my pregnancy this was only once every 4 to 5 weeks, so wasn’t really enough to satisfy all my questions. (Alexis, Australia) Between appointments the Internet helped to provide support and reassurance: Appointments these days seem very few and far between (every 6 weeks, right up to 36 weeks), and I often have concerns and queries in the meantime which can be found out about, and often resolved, using the Internet. Even with such a fab midwife, though, appointments are often very short, and although for her pregnancy is a completely everyday matter, for us expectant mothers it is a huge and important part of our lives for 40 weeks. (Kerry, UK) 57 (62.0) 35 (38.0) Identifying the Internet as an Information Source *Antenatal care shared between a midwife and general practitioner (GP); or midwife and consultant obstetrician; or GP and consultant obstetrician; or midwife, GP, and consultant obstetrician. decision-making.’’ Within each of these themes, several subthemes were identified, many of which were interrelated and overlapping (Fig. 1). The themes were common to all the focus groups. The findings are presented under the headings of the theoretical framework and the master themes. For all the women the Internet was already a familiar source for information, and many wrote about how they ‘‘use the Internet to search for everything,’’ ‘‘always known it as a source for all types of information.’’ Some used it for work, entertainment, wedding planning, studying, shopping, ‘‘… so why wouldn’t I think of using it for pregnancy information?’’ One woman described how her doctor referred her to specific websites: Information Need He knows that I like to research things on my own before making decisions so he has told me to use the Internet and gave me specific web pages to look up. (Helen, Canada) Most women attributed their motivation to search for online information because health professionals did not provide enough information to meet their needs: Considerable discussion ensued about the appealing and distinct characteristics the Internet has to offer. Anonymity was a major attribute of online 340 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 Internet use in Pregnancy Knowledge Validate Information Choice Empowerment INFORMATION NEED Anonymity Share Experiences Control Assisted Decision-Making Social Support Clarity Reassurance Satisfaction Interactivity Fig. 1. Main themes and subthemes related to online information seeking drawn from focus groups. communication, and was particularly important when women wanted confidential advice, to be free to ask questions, and receive support without fear of identification and judgment: Books go out of date quickly. I found the Internet had different perspectives to offer and more current information. (Jeannie, USA) Retrieving Information from the Internet I didn’t want to announce the pregnancy to my family until after 12 weeks, so in the early weeks it was great to anonymously get replies to ‘‘stupid questions’’ which you couldn’t ask others in real life. (Louise, Australia) I also found the anonymity good, especially when I was looking for the answer to a question that I felt ‘too silly’ to ask my midwife. (Jennie, UK) Flexible Internet access was highly valued and the ability to go online at any time and anywhere was perceived as a benefit: The Internet is fast and immediate. I didn’t have to wait until office hours or until someone returned my phone call. I didn’t have to go to a library or bookstore. I could look up information while at work or at home, anytime. (Laura, USA) When compared with other information sources, the Internet had several advantages for these respondents. They criticized books for being expensive, difficult to search, having a one-sided and limited view, and going out of date very quickly. Magazines and leaflets were also criticized for providing limited detail. Overall, they reviewed the Internet as a valuable source for information and described it as a ‘‘font of all knowledge’’: Women used different strategies to retrieve online information, but in the main they commenced their search by entering key words into a search engine such as Google. A desire to critically evaluate a diagnosis or a problem helped focus their search. Many preferred sites supported by health authorities or wellknown medical or academic institutions. Most women recognized the need to distinguish among practices available in different countries. They used more advanced search techniques, such as focusing on their country of residence. Phrases, quotation marks, and extra words helped to narrow their searches. They articulated an understanding of how these techniques helped to focus their search to provide ‘‘authentic’’ choices: I used Google first of all … limiting my search to NZ pages. I read through the summaries of the first few hits and chose the first commercial site because I knew that would give me a quick and basic overview, rather than an overly scientific one. (Chaucey, New Zealand) Numerous participants shared alternative search strategies, which included going directly to websites advertised in an information leaflet they had been given or by starting a ‘‘thread’’ on the topic on a discussion forum: When I was a kid, my parents were big ‘investors’ in encyclopaedias … Google is the encyclopaedia of this century. The Internet contains so much information that can be accessed in seconds. (Infinity, Australia) I would visit open discussion forums that were debating the issue or, begin a thread myself and ask for the opinion of others. (Angie, UK) The magazines all seemed to say the same thing … My health professional had only one opinion and appointments are short. Participants reported that when they found websites they liked, they would often ‘‘bookmark the site’’ or 341 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 ‘‘add to my favorites’’ so that they could return to it at a later date. When the women were asked how they knew they had actually found what they were looking for, most reported that they stopped searching when they found the desired information repeated on a number of sites. Some had to find at least three articles to confirm and support the findings. Several stopped searching when they felt ‘‘satisfaction’’: I wanted to make sure what I was experiencing, was not unique to me, that other women had experienced the same thing. (Noelle, Canada) Stopping searching for me was often more to do with being satisfied that I had learned all I could on the topic (a bit like knowing when you’re full at the dinner table). (Tania, New Zealand) Appraising Information from the Internet I would stop searching when I thought that I had enough information to make an informed decision ⁄ opinion. (Susan, Australia) For others, the search was ongoing: I searched for things right up until the day I went into labour! I found that throughout my pregnancy I could always find information (either based on personal experiences of others) or factual information relevant to the stage I was at. Now I have had my baby, I still use the Internet a lot for gathering information and experiences. (Elizabeth, UK) Using the Internet to Share Experiences The recent advances in web-based systems for social networking and logging experiences create communities in which online users with common interests gather ‘‘virtually’’ to share experiences, ask questions, or provide emotional support and self-help. The women in this study discussed the benefits of network connectivity. They used online discussion forums to gain support from other pregnant women or mothers, which in some instances was in the context of social isolation: My ‘real-life’ friends didn’t have any experience of pregnancy, so the Internet forums I visited provided me with ‘friends’ who had been through it before, or were going through the same experiences as myself. (Nicky, UK) Many wrote that online communities offered them the opportunity to share experiences. By connecting with other women, they were able to get a more realistic picture of what was ‘‘normal’’ and felt reassured when they were able to confirm that the symptoms they were experiencing were typical of pregnancy. The big advantage getting health information from the Internet is that you have ready access to women who have experienced pregnancy and the range of complications, not just health professionals who have studied them. (Kristin, Australia) Having identified online information sources, it was necessary to explore how the information was appraised. Women used an interesting range of validation techniques to confirm their findings. They evaluated information sourced from the Internet mainly by comparing websites and cross-checking information, looking for consistent results. A general opinion was that if the same information was repeated on several sites ‘‘it must be correct.’’ I read several websites to see if the information was similar. When I found a pattern, I took it as correct. (Becky, New Zealand) In addition, some compared the information with their own initial beliefs, or other information sources such as online forums, family and friends, health professionals, books, and leaflets. I knew I had the information I was looking for generally after searching a number of sites and comparing a number of sources of information and when I felt satisfied I had learnt all that I could on a particular topic. I also liked to compare ⁄ discuss what I had found on the Internet with other sources, such as my midwife, obstetrician, GP, textbooks, etc. (Tania, New Zealand) Many women were aware that the Internet had the potential to provide ‘‘unreliable’’ information, and some were skeptical of Internet-based information. I look for information to be evidence based and supported by research. If I find the same or similar information on websites, which I consider to be reputable, then I consider that the information is correct. It also has to make sense to me, i.e., be explained ⁄ justified in logical scientific terms. While I do consider information from other websites, I try to be mindful of the fact that those sources might have agendas, which do not align with mine. (Tina, Australia) Only a few remarked that the Internet domain suffix would influence the sites they would consider trustworthy. In general, they reported trusting information from reputable sources such as ‘‘government’’ or ‘‘hospital’’ websites. Many women also realized that the information 342 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 they found might not necessarily be applicable to them, and it should not be taken at face value. For example: It’s hard to really ever know if the info is correct because one’s health condition might differ slightly or there may be different factors surrounding it. If the same answer turned up in many websites, particularly government health websites or national organisations websites, then I can only ‘‘assume’’ it’s correct. (Pauline, Australia) Some considered whether or not the organization presenting the online information had anything to gain financially, and if it had, they were less likely to trust that specific source. Concerns About Online Information The minority with concerns about the quality of online health information were uncertain because of inconsistencies among website(s). In addition, many participants disclosed how information retrieved could cause stress and anxiety. While finding out about complications or conditions associated with their pregnancy, they were not prepared to read about the worst case scenarios that caused unnecessary worry. Several women wrote that some of the information they read ‘‘strayed from balanced’’ into ‘‘scare mongering’’: At 30 weeks an ultrasound came back with the possibility of a lesion on my baby’s lung. I had to wait 4 days before I could speak with either my own doctor or the OB and have a followup ultrasound. I panicked and went to the Internet to research on my own. All I found were horror stories and worst-case scenarios (death rates, etc.) involving what ‘‘could’’ have been seen on my baby. The stress of that research was too much for me to handle, and I was an emotional wreck for 4 days waiting for my appointment with the obstetrician. (Kerri, Canada) With information ‘‘overload’’ or ‘‘too much’’ of the ‘‘wrong information,’’ many women talked about how the information could make them ‘‘paranoid,’’ ‘‘anxious,’’ or ‘‘frightened.’’ You can come across all sorts of issues and problems that you may never encounter in your pregnancy. (Susan, Australia) Use of Information Retrieved Most women reported discussing the information with a health professional. The main uses of the information were to validate information, aid empowerment, and assist decision-making. Internet to Validate Information Many wrote that they used the Internet to clarify information received from other sources—health professionals, family friends, or literature, such as pregnancy books and leaflets: For me it was more to confirm what a doctor had said. Silly, I know, but I just wanted to understand it some more, which it helped me to do. (Jess, New Zealand) Information to validate information in itself for some had a reassuring effect: My first child had some shoulder dystocia when he was born, and the doctor decided to induce me 2 days after my due date with my second pregnancy. I was upset about this decision but not quite brave enough to demand an explanation. Fortunately I was able to find a fantastic website which explained the condition, the likelihood of it recurring, and the potential results. This convinced me that my doctor was making the right decision. (Jessy, Canada) Internet to Aid Empowerment Many women talked about the information they acquired, that it made them feel ‘‘empowered,’’ ‘‘in control,’’ and ‘‘informed,’’ and gave them strength and confidence to speak to health professionals as ‘‘an equal’’: I felt really empowered having such an amazing resource available from my own home … it put me in control to a degree, and I feel really lucky that I was pregnant in this decade and not in the ‘‘old days’’ where all info came from a medical professional, who often gave only their OPINION and not balanced info … I found that if I researched a topic, and THEN approached my doctor, I got a more ‘‘honest’’ answer (more detail). Having the ability to research at home helped me to make informed choices during my pregnancy… (Rhianna, Australia) Internet to Assist with Decision-Making Internet information increased women’s ability to become engaged in decisions pertinent to their pregnancy. It provided them with information about treatments, options, and consequences. It assisted decision-making by giving them a greater understanding of available choices: I asked on a couple of forums about different experiences with hospital vs. shared care with a GP. From the different opinions and experiences on this topic, I made the decision to go with shared care. It was mainly personal stories on this issue that influenced my decision. (Infinity, Australia) BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 Women talked about using the Internet to weigh up the risks and benefits of options available, with the aim of making an informed choice: I was in two minds about having the triple test at 16 weeks, as I did not feel the result of this should change how I proceeded with my pregnancy. After researching this further I found enough information about the risks and benefits associated with the test to help me make my decision. (Teresa, UK) Women used information to make decisions about themselves; to help their health professionals make decisions; and to engage in shared decision-making. Timely information led to more knowledgeable decisionmaking. Seeking information proved to be a powerful means by which women took control and actively addressed their information needs. None spoke negatively about how the information was perceived by their health practitioner. The majority still valued their health professional’s opinion. As one participant concluded: There is no substitute for professional advice that is specific to your situation. (Tina, Australia) Discussion This study found that infrequent antenatal appointments and a continual need for information triggered the use of the Internet. According to Cooke, pregnant women have been used to getting pregnancy information by means of health professionals and leaflets (21). There is debate in the literature about the benefit of leaflets as part of the consumer’s decision-making process. Previous researchers (3,22) found leaflets and professional consultations to be essential in assisting patients with their decision-making process, whereas Stapleton et al (23) noted that the distribution of pregnancy information leaflets to pregnant women did not facilitate decision-making. For the women in this study, leaflets or books were not universally acceptable because of their ‘‘limited,’’ ‘‘biased,’’ and most often ‘‘out-of-date’’ information. In previous studies, we quantitatively showed that the Internet prepares pregnant women to communicate with health professionals and plays a role in decision-making (10,13). The qualitative descriptions enrich the findings from the survey data by illustrating how the Internet has the potential to inform women’s decision-making about pregnancy-related issues. Although many of the women in this study understood the competing demands on health professionals, they criticized them for failing to provide appropriate information to allow women to make informed choices. Insufficient time at consultations is a potential barrier to patient engagement 343 and shared decision-making, impeding the opportunity for patients to make informed choices (24,25). The positive benefits for both the individual and the organization are well documented when patients have an active informed role in decisions about their care (1,26). Woolf et al claim that health professionals are poor at providing appropriate information, even in this era of great access to information, when consumers of health care want greater engagement in health care choices (27). Jenkins defines decision-making as a process that begins with a problem or situation associated with lack of clarity or inconsistencies that need resolving (28)—very much the case for some of the women in this study. As Edwards and Elwyn (2) and Baumann and Dauber (29) stated later, decisions are also made in the absence of problems, and may involve choosing from a number of alternative options, courses, or actions. Not all the women in this study looked up information to solve a ‘‘problem.’’ Instead, they wanted to understand their options to make informed choices about various aspects of their care. When equated with other information sources, the Internet had several advantages for the participants, such as interactivity, information tailoring, and anonymity. Through online communities, study women collaborated and networked with other pregnant women to seek information, share experiences, and determine availability of support. This finding is also borne out by previous studies (30–32). Online pregnancy discussion groups or support groups were viewed as a positive connecting experience—‘‘very useful’’ and ‘‘practical,’’ as women were able to share their ‘‘stories’’ with one another. According to Hedrick, a common coping strategy is to compare oneself with others to determine how well one is doing (33). The online community gave women the opportunity to ‘‘connect with others in similar situations.’’ For many women, the groups reduced anxiety and isolation, provided reassurance, and assisted their decision-making. Hoddinott and Pill examined antenatal and postnatal expectations of first-time mothers to clarify their decision about whether or not to initiate breastfeeding (34). They found that the women who felt well prepared and coped best postnatally were those who had support from others with similar experiences. This study supported previous findings by Adler and Zarchins (35). They used a virtual focus group as an online support mechanism for pregnant women confined to home bedrest, and reported that online support made the women ‘‘feel they were not alone.’’ Many women described how they used the Internet for reassurance, but no generally accepted definition exists of what reassurance actually means within health care and its therapeutic value is controversial (36). According to Bessell et al, using the Internet for health information has the potential to harm or benefit users (37). Although 344 BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 the women in this study mainly viewed the Internet as a positive resource, it did come under some criticism. It was blamed for ‘‘scare mongering,’’ similar to its effects noted in two previous studies (38,39), both of which observed that it can be a dangerous tool. Participants in this study searched for online information using a range of techniques from simple one-word searches and advanced methods to suboptimal techniques. Few women described using criteria mentioned in several published guides for assessing online health information (40–42). Yet, contrary to findings where consumers were observed using information not applicable to their health setting (43), the women in this study generally reported a strong awareness of accessing sites linked to their country of residence. It could be suggested that women are embracing the Internet as a ‘‘decision aid.’’ However, one could argue that, to be recognized as a ‘‘decision aid’’ tool, pregnancy-specific websites would have to be evaluated to determine if they met International Patient Decision Aids Standards (44), which define the criteria by which all decision aids are measured. Strengths and Limitations This study is the first qualitative research that has been undertaken to explore pregnant women’s use of the Internet in pregnancy and creates a foundation for further research. Particular strengths of this study include the use of online focus groups for data collection and the power of the study to access a diverse global sample in real time. The use of asynchronous communication is still very much a novel approach within social science research. Although more than adequate for qualitative research, the participants were limited to those from more affluent, English-speaking countries. The focus groups were large enough to provide a diversity of opinions and conducted across five countries; however, it could be argued that there may be geographic or cultural differences across other countries in relation to Internet use in pregnancy, and hence the findings cannot be universally generalized. Conclusions With the proliferation of health sites on the Internet, pregnant women now have the potential to have the same access to medical information as health professionals. Findings from this study suggest that they are becoming informed consumers who want more control over decisions affecting their maternity care. The use of the Internet by pregnant women to seek health information and advice suggests a lack of information available from health professionals. As a result of the pressure on the health professional’s time, women may not be receiving adequate information. The onus is on health professionals to acknowledge that women access the Internet for support and pregnancy-related information to inform their decisionmaking. Health care practitioners ideally should initiate as much dialog as possible, early in pregnancy, directing women where to look for accurate, comprehensive, and understandable online pregnancy health information. In this way, women will avoid becoming overwhelmed with extraneous and often conflicting information. Both practitioners and women need to recognize the necessity to evaluate online health information critically. Health professionals can enhance autonomy by embracing the concept of shared decision-making and being prepared to discuss the resulting information so that women can make informed choices about their care. This study highlights the scope for further research. For policy and practice development, it would be valuable to establish the short- and long-term effects and adverse effects (if any) of specific pregnancy-related Internet informed decisions (e.g., on mode of birth, induction of labor, or infant feeding). Future research should evaluate the content of websites containing specific pregnancy-related information as potential. Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank the Department for Employment and Learning, Northern Ireland, for supporting and funding this research, and all the women who participated in the study. References 1. Kinnersley P, Edwards AGK, Hood K, et al. Interventions before Consultations for Helping Patients Address Their Information Needs, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 3). Chichester, UK: John Wiley, 2007. 2. Edwards A, Elwyn G., eds. Shared Decision-Making in Health Care—Achieving Evidence Based Patient Choice, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. 3. O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision Aids for People Facing Health Treatment or Screening Decisions, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 3). Chichester, UK: John Wiley, 2009. 4. Kirkham M, ed. Informed Choice in Maternity Care. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 5. Spoel P. The Meaning and Ethics of Informed Choice in Canadian Midwifery, 2004. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http:// www.inter-disciplinary.net/ptb/mso/hid/hid3/spoel%20paper. pdf. 6. Childbirth Connection. Journey to Parenthood: Informed Decision-Making in Your Pregnancy. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http://www.childbirthconnection.org/article.asp?ck= 10479. BIRTH 38:4 December 2011 7. Internet World Stats. Usage and Population Statistics, 2011. Accessed July 17, 2011. Available at: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm. 8. Pandey SK, Hart JJ, Tiwary S. Women’s health and the Internet: Understanding emerging trends and implications. Soc Sci Med 2003;56(1):179–191. 9. Bernhardt JM, Felter EM. Online paediatric information seeking among mothers of young children: Results from a qualitative study using focus groups. JMIR 2004;6(1):e7. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2004/1/e7/. 10. Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. A web-based survey of midwives’ perceptions of women using the Internet in pregnancy: A global phenomenon. Midwifery 2011;27(2):273–281. 11. Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. Pregnant women’s use of the Internet: A review of published and unpublished evidence. Evid Based Midwifery 2006;4(1):17–23. 12. Kuhlthau C. Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex, 1993. 13. Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. Internet use in pregnancy informs women’s decision-making: A web-based survey. Birth 2010;37(2):106–115. 14. Kalbach J. ‘‘I’m feeling lucky’’: Emotions and information seeking information. Interactions 2004;11(5):66–67. 15. Lehoux P, Poland B, Daudelin G. Focus group research and ‘‘the patient’s view.’’ Soc Sci Med 2006;63(8):2091–2104. 16. Turney L, Pocknee C. Virtual focus groups: New frontiers in research. IJQM 2005;4(2):32–43. 17. Salmon G. E-Moderating: The Key to Teaching and Learning Online. London: Routledge Falmer, 2003. 18. Madge C. Exploring Online Research Methods, 2006. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http://www.geog.le.ac.uk/orm/ questionnaires/quessampling.htm. 19. Nvivo 7. Nvivo 7 Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Victoria, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2007. 20. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, eds. Analysing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge, 1994:173–194. 21. Cooke P. Helping women to make their own decisions. In: Raynor MD, Marshall JE, Sullivan A, eds. Decision-Making in Midwifery Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005:127–142. 22. Ford S, Schofield T, Hope T. Are patients’ decision-making preferences being met? Health Expect 2003;6(1):72–80. 23. Stapleton H, Kirkham M, Thomas G. Qualitative study of evidence based leaflets in maternity care. BMJ 2002;324(7338): 639–643. 24. Le´gare´ F, Ratte´ S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73(3):526–535. 25. Godolphin W. Understanding decision-making in healthcare and the law: Shared decision making. Healthc Q 2009;12:e186– e190. 26. Sandford J. Accessing health information in a hospital setting: A consumer views study. Aust Health Rev 2003;26(1):138–144. 345 27. Woolf SH, Chan ECY, Harris R, et al. Promoting informed choice: Transforming health care to dispense knowledge for decision-making. Ann Intern Med 2005;143(4):293–300. 28. Jenkins M. Improving clinical decision-making in nursing. J Nurs Educ 1985;24(6):242–243. 29. Baumann A, Dauber R. Decision-Making and Problem Solving in Nursing: An Overview and Analysis of Relevant Literature. Toronto: Literature Review Monograph, Toronto University, 1989. 30. Miyata K. Social support for Japanese mothers online and offline. In: Wellman B, Haythornthwaite C, eds. The Internet in Everyday Life. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 2002:520–548. 31. Drentea P, Moren-Cross JL. Social capital and social support on the web: The case of an Internet mother site. Sociol Health Illn 2005;27(7):920–943. 32. Orgad S. The transformative potential of online communication: The case of breast cancer patients’ Internet spaces. Feminist Media Studies 2005;5(2):141–161. 33. Hedrick J. The lived experience of pregnancy while carrying a child with a known, nonlethal congenital abnormality. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2005;34(6):732–740. 34. Hoddinott P, Pill R. Qualitative study of decisions about infant feeding among women in the East End of London. BMJ 1999;318(7175):30–34. 35. Adler CL, Zarchin YR. The ‘‘virtual focus group’’: Using the Internet to reach pregnant women on home bed rest. JOGNN 2002;31(4):418–427. 36. Teasdale K. The concept of reassurance in nursing. J Adv Nurs 1989;14(6):444–450. 37. Bessell TL, McDonald S, Silagy CA, et al. Do Internet interventions for consumers cause more harms than good? A systematic review. Health Expect 2002;5(1):28–37. 38. Lavender T, Campbell E, Thompson S, Briscoe L. Supplying women with evidence based information. Foundation of Nursing Studies Dissemination Series; Developing Practice Improving Care 2003;2(4):1–4. 39. Lalor G, Devane D, Begley CM. Unexpected diagnosis of fetal abnormality: Women’s encounters with caregivers. Birth 2007; 34(1):80–88. 40. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Assessing the Quality of Internet Health Information, 1999. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/data/infoqual.htm. 41. Charnock D. The DISCERN Handbook: Quality Criteria for Consumer Health Information. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998. 42. Commission of the European Communities, Brussels. eEurope 2002: Quality criteria for health related websites. J Med Internet Res 2002. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http:// www.jmir.org/2002/3/e15/. 43. Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, Sa E. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web: A systematic review. JAMA 2002;287(20):2691–2700. 44. International Patient Decision Aids Standards Instrument. IPDASi Assessment. Accessed March 10, 2011. Available at: http:// www.ipdasi.org/.

© Copyright 2026