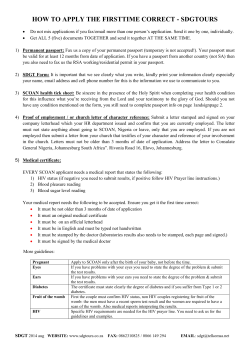

Series Combination HIV prevention for female sex workers: what is the evidence?