Student Name Peter Strempel Student ID Number n

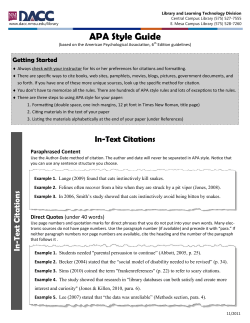

Science and Engineering Faculty ● INN330 Information Management Assignment Cover Sheet Student Name Peter Strempel Student ID Number n 2 5 9 4 Subject INN330 – Information Organisation Lecturer Alexandra Main Date Due 27 October 2013 1 1 1 By submitting this assignment: I/we declare that I/we am/are aware of the University rule that a student must not act in a manner which constitutes academic dishonesty as stated and explained in the QUT Manual of Policies and Procedures (Section C, Part 5.3 Academic dishonesty) or at http://www.mopp.qut.edu.au/C/C_05_03.jsp. I/we confirm that this work represents my/our individual effort and does not contain plagiarised material. 1. Introduction ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 2. Key features of the AEC ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 4 2.1 Legislation, Finance, JSCEM, Statutory Appointees ------------------------------- 5 2.2 Structure and functions -------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2.3 Strategic direction --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 3. Environmental analysis ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 11 4. Some key features of information and knowledge management ------------------- 14 5. Audit ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 15 5.1 Governance and tacit knowledge ----------------------------------------------------- 15 5.2 Compliance, capability and explicit knowledge ------------------------------------ 16 6. Change without turbulence ------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 6.1 The champion ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 17 6.2 The tiger team ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 17 6.3 The Environment -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 18 6.3.1 Encouragement and rewards 18 6.4 The process: strategy in microcosm -------------------------------------------------- 19 6.4.1 Identifying information and knowledge 19 6.4.2 Generating knowledge 19 6.5 Documentation ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 20 7. Conclusion ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 21 8. References --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 22 Examining the principal features of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) reveals a complex organisation with a rigid silo structure nevertheless required to deliver innovation across a broad range of capabilities and outcomes. The examination becomes more complicated still when accompanied by an environmental analysis of key challenges facing the AEC, and the opportunities they may represent. However, reviewing the details within an information and knowledge management (IKM) framework highlights some features of the organisation and its environmental factors that could be leveraged to pioneer a modularised, iterative IKM strategy. The approach proposed here recognises that traditional IKM starting points, like organisation-wide information audits and analyses, represent an uncertain return on investment (Griffiths, 2010, pp. 216-217; Orna, 2008, pp. 558-559). Instead we will focus on immediate problem-solving to address strategic goals, creating and demonstrating the value of IKM by its direct application to resolve a strategic issue: fully electronic voter registration. This IKM model calls for the AEC’s senior management to launch a pilot project simulating a high-pressure environment in which a tiger team of selected staff creates a comprehensive plan to address the issue from all branches of the AEC’s capabilities. The outputs of this project are to be detailed options for addressing the chosen objective, but also a documented IKM process that can be replicated horizontally, for specific problem solving activities, and vertically for an organisational IKM realignment. The contemporary AEC has its roots as a function within the Department of Home Affairs from 1902, becoming the Australian Electoral Office in 1973, and the statutory authority it is today in 1984. The AEC administers and is bound by 11 pieces of legislation, listed in Table 1 below, to deliver a diverse range of electoral and information services (Australian Electoral Commission, 2012, pp. 12-14). The organisation is chaired by a serving or retired federal court judge, presiding over a commission that includes the Australian Electoral Commissioner and a non-judicial commissioner (Australian Electoral Commission, 2004, p. 1; Australian Electoral Commission, 2011; Brent, 2012, paras. 14-17). In addition to the three-person Commission, the AEC includes a deputy commissioner, seven state and territory electoral officers, plus an extra one for the Australian Capital Territory during election periods, two first assistant commissioners, and a staff of 878 people, as shown in Table 2 below (Australian Electoral Commission, 2013; Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918, s. 19-35; Department of Finance and Deregulation, 2013, p. 88). The AEC receives its budget and key performance indicators from the Minister and Department of Finance (formerly the Department of Finance and Deregulation). Table 3, below, illustrates how the $381 million budget for 2013/2014 is split across three major ‘outcomes’ areas (Department of Finance and Deregulation, 2013, p. 3, 86-98). In another line of accountability, the AEC may be invited to deliver reports and recommendations to the Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM), or it may do so under its own initiative. The organisational structure, illustrated in Figure 1 below, is divided by function: Finance and business services; legal and compliance; elections; roll management; education and communication; strategic capacity; information technology; and people services (Australian Electoral Commission, 2012, p. 10). The AEC Strategic Plan for 2009 - 2014 does not mention IKM, instead focusing on ‘modernisation’, ‘collaboration’, and ‘investing in our people’ (Australian Electoral Commission, 2009). It must be assumed that the AEC defers to the Australian Government Information Management Office (AGIMO) within the Department of Finance, which has published a whole-of-government ICT strategy for 1012 - 2015. However, that strategy focuses solely on more effective use of IT systems (Department of Finance and Deregulation, 2012, pp. 5-13). There is no mention of IKM outside an IT perspective. Potential challenges and opportunities for the AEC revealed by means of a PEST analysis (based on a method explained by Gimbert, 2011, pp. 4749) breaks down the strategic environment for the organisation into political, economic, social and technological factors. The main features of this analysis are illustrated in Figure 2 below. While there are a number of issues arising from the analysis that deserve detailed attention, for the purpose of this strategy proposal the focus is directed immediately to the most notable opportunities. From the AEC’s point of view a fully electronic voting system might be a worldbeating achievement. Optimistic assessments have been made of trials by the Victorian Electoral Commission in this area, but it is acknowledged that significant security and technical issues remain to be addressed (Buckland & Wen, 2012, pp. 30-32). There is also a school of thought much less optimistic about the feasibility of overcoming security concerns about electronic voting altogether (Simons & Jones, 2012, pp. 76-77). It appears that progress on electronic voting relies on technical and political resolutions of complex privacy and security issues beyond the AEC’s immediate capacity to address. However, a step towards the resolution of such issues, and a challenge in its own right, is fully electronic voter registration – a process allowing voters to enrol or change their details entirely electronically, without any requirement for paper-based verification. This challenge, and related issues, span all the environmental dimensions of the PEST analysis, as highlighted in Figure 2: 1. Politically: Voter registrations and updates were identified as a critical shortcoming during the 2010 election, and, in a separate development, resulted in a Federal Court ruling that some electronic signatures were to be accepted without requirement for an original as verification (Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, pp. 5-19); 2. Economically: Manual data entry of voter registrations is a major cost component of the AEC’s operations and was identified as a major shortcoming during the 2010 election (Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, pp. 21-41); 3. Socially: Australians increasingly expect to be able to transact online in all aspects of contemporary life, dovetailing with Australian Government priorities to more effectively use technology (Department of Finance and Deregulation, 2012, pp. 5-16) and the AEC’s own strategic goal of modernisation (Australian Electoral Commission, 2009, p. 2); and 4. Technologically: The AEC now has extensive power to electronically cross-check electoral roll details with other government agencies (Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Protecting Elector Participation) Act 2012, schedules 1-2). Technology options for identity verification techniques already exist (Buckland & Wen, 2011, pp. 28-29). What remains is for a solution to be tailored to the AECs capabilities and governance requirements. To consider how the AEC might leverage its capabilities to develop an electronic voter registration system, it is appropriate to examine the principal features of IKM frameworks that are relevant to this task. Information and knowledge management are sometimes treated as separate endeavours, but they are presented here as a continuum in which the knowledge emphasis is at the strategic end (Buchanan & Gibb, 2007, pp. 162-163; Guechtouli, Rouchier & Orillard, 2013, p.48; Henczel, 2001, pp. 49-50). The idea is that information should be harnessed to generate and direct knowledge towards organisational goals. We distinguish here between explicit and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is characterised as capable of being transcribed or otherwise passed on. Tacit knowledge is more personal, intuitive, experience-based, and not always transferrable (Frické, 2009, p. 136; Lopez-Nicolas & Merono-Cerdan, (2013), pp. 503-504; Randles, Blades & Faldalla, 2012, p. 68). Tacit knowledge is sometimes seen as the consequence of ‘doubleloop’ or ‘generative’ learning, which is the transformation or creation of new knowledge from existing information or knowledge (Arling & Chun, 2011, pp. 231-232; Lambe, 2011, p. 190). Facilitating innovation through the generation and embedding of knowledge in an organisation requires the right environment for information and knowledge to be freely exchanged. Some research suggests that one of the most important environmental aspects is a flexible organisational structure that fosters workplace social contexts or networks, like communities of interest, practice or expertise (Arling & Chun, 2011, pp. 240-244; Guechtouli, Rouchier & Orillard, 2013, p.48, 6465; Teng & Song, 2011, pp. 112-114). Others stress the desirability of creating a sense of urgency or crisis (Grant, 2013, p. 90; Pavlak, 2004, p. 8; Snowden & Boone, 2007, pp. 71-75). The graphical representation of the AEC’s principal IKM features in Figure 3, below, illustrates a strong focus on top-down governance and control, guided by individuals possessing significant tacit knowledge about how government, the public service, and public administration works, including career-length intangibles like personal networks of contacts and relationships that play mostly invisible but important parts in their personal effectiveness at a senior management level. Governance and oversight are recognised as legitimate and necessary AEC functions, but the tacit knowledge embodied by the statutory appointees and professional employees is pragmatically recognised as unlikely to be embedded, or even embeddable, in the organisation. Nevertheless, this tacit knowledge is a valuable asset, described variously as human, social or intellectual capital (Buchanan & Gibb, 2007, p. 162; Coyte, Ricceri, & Guthrie, 2012, pp. 790-792; Teng & Song, 2011, p. 104), information capital (Guechtouli, Rouchier & Orillard, 2013, pp.48-49), or knowledge capital (Chen, Horstmann & Markusen, 2012, p. 2). Below the executive management layer is a substantial human resources base of almost 880 staff. This base is characterised principally by the explicit knowledge of methods, processes and procedures related to performing specific tasks in order to comply with governance requirements. However, the silo structure of the organisation, segregated by function, represents a significant barrier to ‘effective information flow’ and ‘the overall value that can be generated’ (Buchanan & Gibb, 2008b, p. 151) in which information flows and opportunities for crossfunctional cooperation are constrained by a ‘discomfort with uncertainty’ (McLeod & Childs, 2013, p. 126), and possibly mistrust and lack of recognised common causes. Regardless of the rigidities of the organisational structure, the capabilities and leadership necessary to drive innovative knowledge creation exist within the AEC, and the proposed approach that follows is designed to harness this strength. The process outlined here calls for: 1. A senior champion for innovation; 2. A team to discover, develop and document the capabilities available and needed for a specific innovation; 3. An environment in which the team can generate the knowledge required for innovation; and 4. A process that guides and demonstrates repeatable information processing and knowledge generation. The Commissioner must be a visible champion of the electronic voter registration pilot project. Moreover, either he or his deputy must participate in at least a casual capacity in the team and its progress, though not so much as to deter the necessary frank and robust exchanges described below. Heightening the function of a matrix team to that of a tiger team places extraordinary demands on its members, requiring a ‘high level of coordination and a deep interpersonal dialog’ derived from ‘uninhibited constructive conflict’ without ‘threat of repercussions from organizational politics’ (Pavlak, 2004, p. 8). Care must be taken to select individuals with existing professional skills, organisational insights, and the capacity to set aside usual organisational norms for the purpose of this special project. The size of the team is dictated by the organisational structure itself (see Figure 2 above). At least one member should be selected from each of the functional silos. The team should not be so large as to encourage internal divisions, and it must include an independent, external facilitator. The facilitator’s function will be to keep the group on track with pre-determined objectives, timelines and deliverables from a position of unimpeachable neutrality. To create sufficient distance between normal organisational routines and conventions it is recommended that normal operational rules are explicitly suspended to create a ‘strategic community’ (Kodama, 2007, pp. 16-17). It is to be an environment in which knowledge can be shared in the manner of ‘social network stimulation’ designed to overcome barriers to ‘cross-silo collaboration within and across the boundaries’ using ‘local cultures and capabilities’ (Snowden, 2005, p. 558). This environment permits replication of a key feature of Nonaka’s ‘middle-updown management’ model, with a team ‘drawn from different functional perspectives [able] to engage in the give-and-take of knowledge creation’ (Teece, 2013, p. 20). It is desirable for the team to be relocated away from their normal working environments to remove distractions and the comfort zone of familiarity. To help create a sense of urgency and gravity in the tiger team, the initial brief should set an ambitiously short time-frame. Urgency and commitment can also be heightened by mention the historic achievements of other tiger teams, like those who worked on the Manhattan Project, the Cuban Missiles Crisis, or implementing a national economic stimulus package during a financial crisis (Davidson, 2009, para. 9; Pavlak, 2004, p. 8). It is recommended that sincere performance-based group and individual reward structures are offered that consider both intrinsic (motivational) and extrinsic (financial ) components (Zhang, Zhou & McKenzie, 2013, pp. 179-180; Peltokorpi, 2013, pp. 266-268), possibly with a stronger emphasis on extrinsic team rewards to generate an immediate commitment to a short-term, one-off project (Snowden, 2005, pp. 559560). However, fast-tracking career development and organisational recognition for outstanding commitment should also be considered as reward options. The principal focus is on a creative and open articulation of all possible options for implementing fully electronic voter registration. An immediate goal is to highlight potential barriers and solutions to an electronic registration system in all functional areas of the AEC. This includes an information architecture, which is a plan for the classification, structuring, and storage of information to make it easy to find and search for the people who need to access it to implement and administer the project (Downey & Bannerjee, 2011, p. 26; Garrett, 2011, pp. 88-101). From that architecture should flow an IKM asset register, information flow and interrelationships mappings, and information and knowledge gap analyses highlighting what information and competencies are missing but required for the tasks identified as necessary (Griffiths, 2010, p216, 221-222; Griffiths, 2012, p. 49; Buchanan & Gibb, 2008a, pp. 89; Buchanan & Gibb, 2008b, p.159). Leading on from considerations about types of information and knowledge necessary, the project must generate specific options and proposals. To ensure that rigorous debate and disagreement does not become personally hostile rather than constructive across the group, a method of dialectic resolution and synthesis will be explained by the facilitator, who will bring all conflict back to its core utility, which is to combine the most useful elements of conflicting ideas to create new ones. The dialectic methods to be used include the Socratic iteration of an idea until the maximum number of prohibitive factors have been removed from it; an advocacy model in which team members seek to persuade each other as a means of discovering strengths and weaknesses in their propositions; a Hegelian consideration of how the world might be changed to suit an idea (a precursor to considering what might be possible with legislative changes); and the resolution of thesis and antithesis by synthesising elements of both into a new thesis, possibly subject to further Socratic iteration (Nielsen, 1996, pp. 280-288; Spender, 2013, pp. 51-53). Dialectics are not the sole methods appropriate for reconciling conflicting ideas, and any alternative method devised or favoured by the team is equally appropriate if it meets the overall objectives of generating ideas and solutions. Guided high-pressure discussions conducted in this manner will demonstrate to participants directly how grappling with specific issues allows them to generate knowledge. Moreover, it will impress on them that the process is repeatable, subject to being carefully documented and adapted to specific purposes. The information product of the tiger team is a report detailing every aspect of its considerations, including its decision-making processes, a proposed project plan with timelines and an outline of resources required to realise the preferred option, and a method for auditing its own work. The elements of this report represent the formula for repeating the process to address other specific issues, or to approach a wider IKM strategy for the AEC, including, in its most complete expression, an organisational transformation from silo-based process orientation to cross functional knowledge orientation. The methods outlined here represent a bold proposal for addressing the need to innovate within an organisational structure that creates significant barriers to change. At each stage, this approach has carefully considered the AEC’s existing mission and strategic goals, with reference to its structure, funding, KPIs, and strategic challenges. To maintain that focus this report has proposed handing over the actual development of an IKM strategy to carefully selected AEC staff, led and championed by its senior management, and with an eye to embedding the intellectual capital of the effort in the organisation by means of a modularised, repeatable method. This approach limits any risk of individual project failure, or negatively disrupting the AEC’s normal operations and performance, at the same time as offering a path for a gradual, iterative and controlled roadmap to a wider organisational shift towards an IKM focus that will enable the AEC to more effectively meet its goals, targets and challenges in the coming decade. Although the approach described here is cautiously incremental, it has the potential to be ground-breaking and visionary in the right hands, leading to an IKM best-practice model not only for the Australian public service, but also for similar organisations around the world. Arling, P.A., & Chun, M.W.S., (2011). Facilitating new knowledge creation and obtaining KM maturity. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(2), 231-250. doi: 10.1108/13673271111119673 Australian Electoral Commission (2004). Behind the scenes: the 2004 election report including national election results. Retrieved from http://results.aec.gov.au/12246/pdf/BehindTheScenes.pdf Australian Electoral Commission (2009). Strategic Plan 2009 – 2014. Retrieved from http://www.aec.gov.au/About_AEC/Publications/Corporate_Publ ications/index.htm Australian Electoral Commission (2011, May 18). Australia's major electoral developments timeline: 1900 - present. Retrieved from http://election.aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_Histor y/Reform_present.htm Australian Electoral Commission (2012). 2011-12 Annual Report. Retrieved from http://www.aec.gov.au/About_AEC/Publications/Annual_Report s/index.htm Australian Electoral Commission (2013). About us. Retrieved on September 3, 2013, from http://www.aec.gov.au/About_AEC/index.htm Brent, P. (2012, November 19). Short history of the electoral roll. The Australian. Retrieved from http://blogs.theaustralian.news.com.au/mumble/index.php/theau stralian/comments/short_history_of_the_electoral_roll/ Buchanan, S., & Gibb, F. (2007). The information audit: Role and scope. International Journal of Information Management 27(3), 159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.01.002 Buchanan, S., & Gibb, F. (2008a). The information audit: Methodology selection. International Journal of Information Management, 28(1), 3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.10.002 Buchanan, S., & Gibb, F. (2008b). The information audit: Theory versus practice. International Journal of Information Management 28(3), 150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.09.003 Buckland, R. & Wen, R. (2012). The future of e-voting in Australia. IEEE Security & Privacy, 10(5), 25-32. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2012.59 Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Clth) s. 18-35. Retrieved from http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/cea1918233/ Chen, Y., Horstmann, I.J., & Markusen, J.R. (2012). Physical capital, knowledge capital, and the choice between FDI and outsourcing. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(1), 1-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5982.2011.01684.x Coyte, R., Ricceri, F., & Guthrie, J. (2012). The management of knowledge resources in SMEs: an Australian case study. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(5), 789-807. doi: 10.1108/13673271211262817 Davidson, J. (2009, February 25). With stimulus contracts, let’s avoid another Katrina. The Washington Post. Retrieved on October 12, 2013, from http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2009-0225/opinions/36773676_1_stimulus-package-private-contractorsworkforce Department of Finance and Deregulation (2012). Australian Public Service Information and Communications Technology Strategy 2012 – 2015. Retrieved on September 29, 2013, from http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/ict_strategy_2012_2015/ Department of Finance and Deregulation (2013). Portfolio Budget Statements 2013-2014. Retrieved on September 26, 2013, from http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/portfolio-budgetstatements/13-14/index.html Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Protecting Elector Participation) Act 2012 (Clth). Retrieved from http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2012A00111 Frické, M. (2009). The knowledge pyramid: A critique of the DIKW hierarchy. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 131-142. doi: 10.1177/0165551508094050 Gimbert, X. (2011). Think Strategically. Hampshire: UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Grant, R.M. (2013). Nonaka’s ‘dynamic theory of knowledge creation’ (1994: Reflections and an exploration of the ‘ontological dimension’. In In G. von Krogh, H. Takeuchi, K. Kase & C.G. Canton (Eds.), Towards Organizational Knowledge: The Pioneering Work of Ikujiro Nonaka (pp. 77-95). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Griffiths, P. (2010). Where next for information audit? Business Information Review, 27(4), 216-224. doi: 10.1177/0266382110388221 Griffiths, P. (2012). Information Audit: Towards common standards and methodology. Business Information Review, 29(1), 39–51. doi: 10.1177/0266382112436791 Guechtouli, W., Rouchier, J., & Orillard, M. (2013). Structuring knowledge transfer from experts to newcomers. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(1), 47-68. doi: 10.1108/13673271311300741 Henczel, S. (2001) The information audit as a first step towards effective knowledge management. Information Outlook, 5(6), 48-62. Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (2010). The 2010 federal election: Report on the conduct of the election and related matters. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Ho use_of_Representatives_Committees?url=em/elect10/report.ht m Kodama, M. (2007). Innovation through boundary management — a case study in reforms at Matsushita electric. Technovation, 27(1–2), 15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2005.09.006 Lambe, P. (2011). The unacknowledged parentage of knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(2), 175-197. doi: 10.1108/13673271111119646 Lopez-Nicolas, C., & Merono-Cerdan, A.L. (2011). Strategic knowledge management, innovation and performance. International Journal of Information Management, 31(2011), 502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.02.003 McLeod, J. & Childs, S. (2013). A strategic approach to making sense of the “wicked” problem of ERM. Records Management Journal, 23(2), 104-135. doi: 10.1108/RMJ-04-2013-0009 Nielsen, R.P. (1996). Varieties of dialectic change processes. Journal of Management Inquiry, 5(3), 276-292. doi: 10.1177/105649269653014 Orna, E. (2008). Information policies: yesterday, today, tomorrow. Journal of Information Science, 34(4), 547-565. doi: 10.1177/0165551508092256 Pavlak, A. (2004). Project troubleshooting: Tiger teams for reactive risk management. Project Management Journal, 35(4), 5-14. Peltokorpi, V. (2013). Governing knowledge processes in project-based organizations. In G. von Krogh, H. Takeuchi, K. Kase & C.G. Canton (Eds.), Towards Organizational Knowledge: The Pioneering Work of Ikujiro Nonaka (pp. 263-282). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Randles, T.J., Blades, C.D., & Faldalla, A. (2012). The knowledge spectrum. International Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(2), 65-78. Simons, S. & Jones, D.W. (2012). Internet voting in the U.S.. Communications of the ACM, 55(10), 68-77. doi: 10.1145/2347736.2347754 Snowden, D. (2005). From atomism to networks in social systems. The Learning Organization, 12(6), 552-562. Snowden, D.J. & Boone, M.E. (2007). A leader's framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68-76. Spender, J.C. (2013). Nonaka and KM’s past, present and future. In G. von Krogh, H. Takeuchi, K. Kase & C.G. Canton (Eds.), Towards Organizational Knowledge: The Pioneering Work of Ikujiro Nonaka (pp. 24-59). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Teece, D.J. (2013). Nonaka’s contribution to the understanding of knowledge creation, codification and capture. In G. von Krogh, H. Takeuchi, K. Kase & C.G. Canton (Eds.), Towards Organizational Knowledge: The Pioneering Work of Ikujiro Nonaka (pp. 17-23). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Teng, J.T.C., & Song, S. (2011). An exploratory examination of knowledge-sharing behaviors: Solicited and voluntary. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(1), 104-117. doi: 10.1108/13673271111108729 Zhang, Y, Zhou, Y., & McKenzie, J. (2013). A humanistic approach to knowledge-creation: People-centric innovation. In G. von Krogh, H. Takeuchi, K. Kase & C.G. Canton (Eds.), Towards Organizational Knowledge: The Pioneering Work of Ikujiro Nonaka (pp. 167-189). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

© Copyright 2026