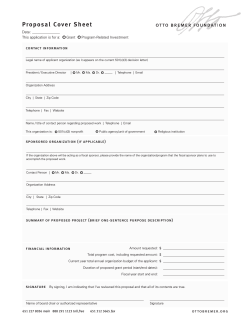

Document 257317