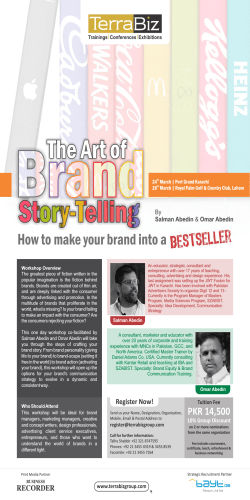

BRAND CONCEPT AND BRAND REACH: A DUAL