5 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological

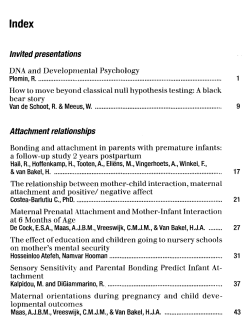

5 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Abstract Attachment theory predicts that early experiences with caregivers affect the quality of individuals’ later (romantic) relationships and, consequently, their mental health. The present study examined the role of intimacy in the current romantic relationship as a possible mediator of the relationship between adult attachment and psychological distress in a clinical and community sample. Results indicated that attachment security was positively, whereas attachment insecurity was negatively related to intimacy in the current romantic relationship. Furthermore, security of attachment was negatively related to loneliness and depression and positively to satisfaction with life. The reverse held for attachment insecurity. Mediational analyses revealed that intimacy in the current relationship only partially mediated the relationship between attachment and psychological distress. Although near perfect mediation was found for fearful attachment in the clinical sample and for preoccupied attachment in the community sample, the findings with regard to the other attachment styles were less clear-cut. Apart from the hypothesized indirect effect of attachment on psychological distress through intimacy, a direct effect of attachment on psychological distress remains. The implication of these findings and suggestions for future research are discussed. Pielage, S.B., Luteijn, F. & Arrindell, W.A. (2005) Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12, 455-464. Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Introduction A basic premise of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980) is that early experiences with caregivers affect one’s functioning in later (romantic) relationships. Repeated interactions with caregivers become internalized as mental models, or ‘internal working models of attachment’, that serve to guide social behaviour and expectations in subsequent relationships across the life span. According to attachment theory, consistent and sensitive parenting leads to the development of a secure attachment style, characterized by interpersonal trust and comfort with intimacy. In contrast, children with insecure attachment styles, whose bids for security have been either ignored or rebuffed (leading to avoidant attachments) or responded to inconsistently (leading to ambivalent attachments), will acquire models of others as rejecting or inconsistent (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters & Wall, 1978). As adults, secure individuals report having more intimate, satisfying and enduring relationships than their insecurely attached counterparts (Collins & Read, 1990; Feeney, 1999; Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Individuals with an insecure attachment style are characterized by a lack of confidence and trust in the supportiveness of significant others and are hampered in their support-seeking behaviour (Simpson, Rholes & Nelligan, 1992; Collins & Feeney, 2004). Indirect evidence supports the hypothesis that insecure childhood attachment constitutes a risk factor for later marital difficulties (Ricks, 1985; Birtchnell, 1993). For most individuals, a satisfying intimate relationship is the most important source of happiness and well-being (Veenhoven, 1987; Russell & Wells, 1994). Conversely, being in a distressed relationship constitutes a major risk factor for psychopathology (Burman & Margolin, 1992). According to attachment theory, individuals with an insecure attachment style risk meeting with unsatisfactory intimate relationships which increases their vulnerability to the development of psychological and physical complaints. As Bowlby puts it: "the psychology and psychopathology of emotion is found to be in large part the psychology and psychopathology of affectional bonds" (1980, pg. 40). Thus, in essence Bowlby put forward a mediational model where attachment influences psychological functioning through the quality of one’s affectional bonds (see Figure 5.1). 88 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Intimacy (Mediator) Adult attachment style (independent variable) Psychological distress (dependent variable) Figure 5.1: Mediational model where intimacy in the current romantic relationship mediates the relationship between attachment style and psychological distress Although a number of studies have demonstrated the predicted associations between attachment styles and relationship quality on the one hand, (for an overview see Feeney, 1999) and between attachment styles and psychological distress on the other hand (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Carnelly, Pietromonaco & Jaffe, 1994; Murphy & Bates, 1997), studies that report on the interplay between these variables are sparse. The present study was designed to examine these interrelationships in an effort to explore the mechanism underlying the link between attachment styles and psychological distress. Given that insecurely attached individuals tend to be more vulnerable to the development of psychological complaints, the goal of the present study was to examine the extent to which this could be accounted for by a lack of intimacy in their current romantic relationship. Specifically, the aims of the present study were to test three hypotheses regarding the interrelationships between attachment, intimacy and psychological distress in a clinical and community sample. First, it was predicted that security of attachment would be positively related to intimacy, whereas insecurity of attachment would be negatively related to intimacy in the current romantic relationship. Second, it was anticipated that security of attachment would be negatively related to psychological distress, whereas insecurity of attachment would be positively related to psychological distress. Third, it was hypothesized that intimacy in the current romantic relationship would function as a mediator in the attachment - psychological distress relationship. 89 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Method Participants and procedure The clinical sample consisted of 92 individuals in the process of psychotherapy who were recruited at several outpatient clinics in the North of the Netherlands. All patients agreed through a written informed consent to the use of their data for scientific purposes. Participating patients were requested to respond to a series of questionnaires regarding “close relationships”. In order to ensure that patients were involved in established relationships, they were required to have dated their partner for at least three months prior to participation. The clinical sample contained 65 women, 25 men, and two individuals who did not report their gender. The mean age was 36 years (SD=9.6); 51 (57%) were married, 17 (19%) were cohabiting and 22 (24%) were Living Apart Together (LAT-relationship). The duration of the current romantic relationship varied from 3 months to 32 years, with a mean duration of 11.4 years (SD=9.6). The educational level of the clinical sample was high: 5% had a primary school level, 33% a higher grade elementary or secondary school level and 62% had a higher educational level. The community sample consisted of 54 men, 65 women, and two individuals who did not specify their gender (N=121) from the general community who agreed to participate in a mail survey on “close relationships”. Participants were required to have dated for at least three months prior to participation. The mean age was 38.2 (SD=12.6) years; 78 (65%) were married, 19 (16%) were cohabiting and 23 (19%) had a LAT relationship. The duration of the current romantic relationship ranged from three months to 43 years with an average of 15.2 years (SD=12.2). The educational level of the community sample was as follows: 18% had a primary school level, 38% a higher grade elementary or secondary school level and 44% a higher education level. Measures To provide comprehensive assessment of adult attachment, two measures were employed. First, attachment was assessed with the Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Participants were requested to indicate on a 7point scale the extent to which each of the four attachment prototypes, secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful, applied to them. For example, the formulation of 90 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample the prototypical description intended to assess fearful attachment reads as follows: ‘I am uncomfortable getting close to others. I want emotionally close relationships, but I find it difficult to trust others completely, or to depend on them. I worry that I will be hurt if I allow myself to become too close to others’. Second, participants completed the Adult Attachment Scale (de Jonge, 1995), a 34item scale measuring secure (7 items), dismissing (14 items), preoccupied (8 items) and fearful (5 items) attachment. The items employ a 5-point response format, from 1= ‘not at all like me’ to 5 = ‘very much like me’. In view of differences in subscale length, Spearman-Brown corrections were used by increasing the number of scale items for each subscale to 20. Alpha reliability coefficients for the community sample were .73 for secure, .91 for the fearful, .93 for preoccupied and .98 for dismissing attachment. In the clinical sample alpha coefficients were .81 for secure, .80 for fearful, .86 for preoccupied and .98 for dismissing attachment. In both samples, intimacy was assessed with the Dutch version of the Waring Intimacy Questionnaire (WIQ; Waring, 1984; Luteijn, Arrindell, Huiskes, Kits, Lenters & Sanderman, 1993). An ‘Overall Intimacy score’ summarizes the degree of intimacy in the current relationship based on the scales’ 44 best discriminating items. The Cronbach's alpha reliability for the overall intimacy score was .87 in the clinical and .88 in the community sample. Current Psychological Distress Loneliness was assessed with the Loneliness Scale developed by de Jong-Gierveld and Kamphuis (1985). This scale has shown to have good psychometric qualities and contains 11 items, e.g., “I really miss a good friend” and "I have many people whom I can trust completely". The possible answers ranged from (1) completely agree to (5) completely disagree. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the loneliness scale was .89 in both the clinical and community sample. Depressive symptomatology was assessed with the Dutch version of Center for epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Schroevers, Sanderman, van Sonderen, & Ranchor; 2001; Radloff, 1979). This 20-item scale assesses current depressive symptoms in the general population. Subjects rate each item on a four-point scale ranging from (1) none of the time to (5) all of the time, indicating the degree to which 91 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample they experienced each symptom in the previous week. Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the CES-D was .92 in the clinical and .87 in the community sample. Satisfaction with life was assessed with the Dutch version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Arrindell, Meeuwesen & Huyse, 1991; Arrindell, Heesink, & Feij, 1999). This scale was designed to assess a person’s global judgement of life satisfaction. The scale consists of five items e.g. ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’ (Pavot & Diener, 1993). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the SWLS was .81 in the clinical and .85 in the community sample. Results Preliminary Analyses As a preliminary analysis, the potential influence of gender was examined. A Multivariate Analysis of Variance, with gender as the independent and the four attachment styles, intimacy in the current romantic relationship, depression, loneliness and satisfaction with life as dependent variables proved nonsignificant in both the clinical sample (F(12, 89) = 1.22; p = .29) and the community sample (F(12, 110) = .78; p = .67). The data for men and women were therefore analyzed jointly. Biographical variables, such as age, level of education and duration of the romantic relationship did not relate substantially to attachment, intimacy, depression, loneliness and satisfaction with life. Therefore, results will be reported for the entire sample. As a second preliminary analysis, differences between the clinical and community sample were analysed. A Multivariate Analysis of Variance, with ‘group’ as the independent and the 4 attachment styles, intimacy in the current romantic relationship, depression, loneliness and satisfaction with life as dependent variables proved highly significant (F(12, 214 ) = 5.65; p < .001). Means and standard deviations for both groups are reported in Table 5.1, as well as the differences between the groups. Compared to the community sample, the clinical sample was less securely and more insecurely attached. Patients experienced less intimacy in their current romantic relationship, they were more depressed and lonely and less satisfied with their lives. 92 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Table 5.1: Means and Standard deviations of the clinical and community sample Clinical sample Community sample M SD M SD F (12,204) RQ- secure 3.74 1.91 4.67 1.80 12.88** RQ- dismissing 3.01 1.74 3.10 1.81 .12 RQ- preoccupied 3.97 1.73 3.52 1.76 3.29+ RQ- fearful 4.58 1.94 3.53 1.88 15.27** AAS-secure 21.68 2.38 22.43 2.50 4.75* AAS-dismissing 33.35 8.11 28.66 7.45 18.59** AAS- preoccupied 18.46 4.02 17.15 3.71 5.48* AAS- fearful 13.63 3.10 11.54 2.57 27.91** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship 28.98 7.81 35.31 6.85 38.12** Loneliness 28.43 10.47 21.58 8.94 25.51** Depresssion 18.25 11.32 10.07 7.71 37.68** Satisfaction with life 21.13 6.90 27.50 6.07 49.38** Attachment N clinical sample = 92; N community sample = 113; * p < .05; ** p < .001; + p=.07 Furthermore, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed among all measures in the study. It should be noted that two attachment measures were included to provide a more complete picture of participant’s attachment styles and to assess the convergence among the attachment scales. As can be seen from Tables 5.2 and 5.3, convergence among the RQ and the AAS was generally modest, ranging from .04 for the dismissing attachment style in the clinical sample to .55 for the preoccupied style in the community sample. Interestingly, there was a very high correlation between the dismissing and fearful attachment styles. As researchers have recently begun to emphasize the importance of using multi-item dimensional scales to measure adult attachment (Brennan, Clark & Shaver, 1998; Fraley & Waller, 1998), and in view of several methodological reservations regarding the stability of the RQ across time and individuals (Pielage, Barelds & Gerlsma, 2006; Pielage, Gerlsma & Barelds, 2006), only results pertaining to the multi-item adult attachment scale will be reported here. As 93 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample expected, security of attachment was positively related, whereas insecurity of attachment was negatively related to intimacy in the current romantic relationship. Furthermore, attachment security was negatively related to both loneliness and depression and positively to satisfaction with life. The reverse was true for attachment insecurity. Table 5.2: Pearson Product moment correlations between adult attachment style (RQ and AAS), intimacy in the current romantic relationship (WIQ), depression (Ces-d), loneliness and satisfaction with life (SWLS) in the clinical sample (N=92) 1 2 3 4 5 - .04 -.15 - -.15 .11 .03 - .20 - 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Attachment 1. RQ – secure 2. RQ – dismissing 3. RQ – preoccupied 4. RQ – fearful 5. AAS – secure 6. AAS – dismissing 7. AAS – preoccupied 8. AAS – fearful -.64** .34** -.51** -.31** -.51** -.04 -.43** -.31** .13 -.29** .23* .55** .31** -.27** .29** .39** -.24* -.18 .67** .26* .42** -.29** .45** .35** -.25* - -.21* -.18 -.24* .36** -.42** -.27** .41** .50** -.54** .63** - .48** -.30** .29** - .00 .31** -.23* - -.24* .19 .16 -.40** .32** -.10 .29** .49** -.49** .47** -.38** .36** -.20 Intimacy 9. WIQ - -.68** -.53** .55** Current psychological functioning 10. Loneliness 11. Depression 12. Satisfaction with life - .56** -.60** - -.72** - N = 92; * p < .05; ** p < .001; + p=.07 94 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample Table 5.3: Pearson Product moment correlations between adult attachment style (RQ and AAS), intimacy in the current romantic relationship (WIQ), depression (Ces-d), loneliness and satisfaction with life (SWLS) in the community sample (N=113) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 -.28** .21* -.01 .28** 9 10 11 12 - .28** -.10 - -.01 -.34** -.16 -.34** .16 -.21* -.25** .06 .04 -.21* -.11 -.05 -.01 -.13 .09 - -.08 - -.17 .12 .27** .13 -.04 .07 .22* .04 -.19* .50** .13 - -.32** -.12 -.09 - .28** .45** -.56** .65** .59** -.43** .19* .38** Attachment 1. RQ – secure 2. RQ – dismissing 3. RQ – preoccupied 4. RQ – fearful 5. AAS – secure 6. AAS – dismissing 7. AAS – preoccupied 8. AAS – fearful - .27** -.31** .27** - .32** -.27** .29** -.38** -.33** .32** -.20* .10 -.34** .31** -.13 .37** -.36** Intimacy 9. WIQ - -.56** -.45** .53** Current psychological functioning 10. Loneliness - .43** -.55** 11. Depression - -.50** 12. Satisfaction with life - N = 113; * p < .05; ** p < .001; + p=.07 Mediational analyses Mediational analyses were conducted to investigate whether intimacy in the current romantic relationship could account for the relationships found between attachment and psychological distress. Given the strong overlap between the measures of psychological functioning (depression, loneliness and reverse satisfaction with life), the three variables were combined to form the sumscore ‘psychological distress’. It should be noted that reporting on the three variables separately would require reporting as many as twenty-four regression analyses. As all results pertaining to the combined sumscore ‘psychological distress’ were similar to the analyses done with each of the variables separately, and in view of clarity of presentation, we decided to report solely on the combined sumscore ‘psychological distress’. Following the method outlined by Baron & Kenny (1986), mediation is established when the following conditions are met: (1) a significant relationship is found between the independent variable (in this case attachment style) and the presumed mediator (intimacy in the current romantic relationship); (2) a significant relationship is found between the presumed mediator (intimacy) and the dependent variable (psychological 95 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample distress) and (3) a significant association between the independent (attachment style) and the dependent variable (psychological distress) is significantly reduced after statistically controlling for the presumed mediator. Conditions 1 and 2 were met in all cases. Therefore, four separate multiple regression analyses were conducted in both the clinical and community sample to test the mediational model for each case. In each regression analysis, psychological distress was regressed on one of the four attachment styles first. Subsequently, on the second step, intimacy in the current romantic relationship was added to the regression equation to investigate whether the amount of variance accounted for by attachment style would be reduced. The results are presented in Table 5.4 and Table 5.5. Table 5.4: Multiple regression statistics with psychological distress as the dependent variable in the clinical sample (N=92) R adj. R2 .38 .14 .70 .48 f2 F β R2 change Regression equation 1 Step 1 15.53** Secure attachment Step 2 -.38** .92 42.22** Secure attachment -.16* Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.62** .34** Regression equation 2 Step 1 .62 .38 .75 .55 57.43** Dismissing attachment Step 2 .62** 1.22 56.06** Dismissing attachment .36** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.49** .17** Regression equation 3 Step 1 .44 .18 .73 .52 21.56** Preoccupied attachment Step 2 .44** 1.08 49.23** Preoccupied attachment .26** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.60** .33** Regression equation 4 Step 1 .35 .11 .69 .46 12.57** Fearful attachment Step 2 Fearful attachment Intimacy in the current romantic relationship .35** .85 39.62** .09 .35** -.64** For the clinical group, when intimacy in the current romantic relationship was added to each of the regression equations, the following results were obtained: (1) The 96 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample relationships between secure, dismissing, preoccupied attachment and psychological distress were reduced but remained significant (2) The relationship between fearful attachment and psychological distress was reduced and became non-significant. Table 5.5: Multiple regression statistics with psychological distress as the dependent variable and attachment style and intimacy as independent variables in the community sample (N=116) R adj. R2 .42 .17 .69 .47 f2 F β R2 change Regression equation 1 Step 1 23.50** Secure attachment Step 2 -.42** .89 50.05** Secure attachment -.25** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.57** .30** Regression equation 2 Step 1 .67 .47 .76 .57 101.26** Dismissing attachment Step 2 .67** 1.32 76.31** Dismissing attachment .49** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.37** .09** Regression equation 3 Step 1 .25 .06 .66 .42 7.81** Preoccupied attachment Step 2 .25** .72 42.14** Preoccupied attachment .13 Intimacy in the current romantic relationship .37** -.62** Regression equation 4 Step 1 .42 .17 .68 .45 24.95** Fearful attachment Step 2 .42** .82 48.37** Fearful attachment .24** Intimacy in the current romantic relationship -.56** .28** The community sample showed the following results: (1) The relationships between secure, dismissing and fearful attachment and psychological distress were reduced but remained significant (2) the relationship between preoccupied attachment and psychological distress was reduced and became nonsignificant. The results indicate that intimacy in the current romantic relationship partially mediates the relationship between attachment and psychological distress. Although near perfect mediation was found for fearful attachment in the clinical sample, and preoccupied attachment in the community sample, the findings with regard to the 97 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample other attachment styles were less clear-cut, indicating that apart from the indirect effect through intimacy, attachment also has a direct, independent effect on psychological distress. Discussion A close, intimate relationship with a romantic partner is probably the most important attachment relationship in adult life. For most individuals, a satisfying romantic relationship is an important source of happiness and wellbeing and a supportive relationship may even protect individuals against the impact of adverse life-events (Brown & Harris, 1975; Russell & Wells, 1999). In contrast, being in a distressed relationship seems to be detrimental to a sense of well-being and psychological functioning (Burman & Margolin, 1992). Attachment theory suggests that insecurely attached individuals risk meeting with unsatisfactory close relationships and that this in turn may prove to be a risk factor for the development of psychopathology (Bowlby, 1980). In line with this hypothesis previous research has shown that insecure attachment is negatively related to relationship quality and positively to psychological complaints (Carnelly et al, 1994; Feeney, 1999; Murphy & Bates, 1997; Shaver & Brennan, 1992). However, studies reporting on the interrelationships between the three variables are sparse. In order to delineate the mechanism through which attachment is associated with the development of psychological distress, the present study addressed the question whether the association found between attachment and psychological distress could be accounted for by intimacy experienced in the current romantic relationship. Overall, the results of the present study replicate previous findings in the sense that security of attachment was positively related to intimacy in the current romantic and negatively related to psychological distress, whereas insecurity of attachment was negatively related to intimacy in the current romantic relationship and positively to psychological distress. However, contrary to the expectation, mediational analysis revealed that intimacy in the current romantic relationship only partially functioned as a mediator between adult attachment and psychological distress. Although near perfect mediation was found for fearful attachment in the clinical sample, and preoccupied attachment in the community sample, the findings with regard to the 98 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample other attachment styles were less clear-cut, indicating that apart from an indirect effect through intimacy, there is also a direct, independent effect of attachment on psychological distress. Furthermore, it is possible that other variables than intimacy in the current romantic relationship may influence the association between attachment and psychological distress. An asset of the present study was the inclusion of a clinical group. Most research on attachment and close relationships is limited by a so-called ‘restriction of range’; community samples are usually biased towards a secure attachment style as insecure individuals may avoid or be hampered in the establishment of a long-term close relationship. Indeed, the clinical sample was more insecurely and less securely attached than the community sample. Furthermore, patients reported less intimacy in their relationship, they experienced more loneliness and depression, and they were less satisfied with their life in general. Interestingly, the pattern of findings in both groups was similar, although they tended to be somewhat stronger for the clinical sample. A point that deserves attention concerns the measurement of adult attachment. In the present study, two self-report measures of adult attachment, the Relationship Questionnaire and the Adult Attachment Scale, were used. To our surprise the convergent validity was modest, with stronger relationships sometimes found between different attachment styles (i.e. fearful with dismissing) than similar styles (dismissing with dismissing). Furthermore, the associations found between the attachment styles and depression, loneliness and satisfaction with life, differed between the two attachment measures. For example, no association was found between loneliness and the dismissing attachment prototype on the RQ whereas the dismissing style of the AAS had the highest association with loneliness. Previous research has addressed the question of the validity of self-report measurement of adult attachment (for reviews see Bartholomew & Shaver, 1998; Crowell & Treboux, 1995; Crowell, Treboux & Shaver, 1999; Stein, Jacobs, Ferguson, Allen, & Fonagy, 1998). Recently, Fraley & Waller (1998) investigated the ‘typological model of attachment’ and found no evidence for four distinct attachment prototypes. According to these authors their data ‘indicate that the typological model traditionally favoured by attachment researchers does not capture the natural structure of attachment security. Rather, they indicate that adult attachment is a quantitatively distributed variable- a variable on which people differ in degree rather than in kind’ (p. 99 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample 108). Fraley and Waller (1998) strongly suggest abandoning the idea of so-called attachment styles and recommend that the latent structure of attachment styles (i.e. avoidance and anxiety) be used in analyses. Perhaps, if the two attachment measures that were used in this study would be compared on the latent dimensions of attachment, convergent validity would improve. Future research should benefit from current knowledge and use more sophisticated multi-item scales to measure adult attachment. Several limitations of the present study should be mentioned. First of all, as with all studies relying solely on the use of self-report methods, the extent to which systematic biases influenced participants’ responses is unclear. However, considering the fact that the results presented here showed patterns that are largely consistent with previous research, it is unlikely that general response styles affected the correlational pattern to a very large extent. Second, the use of a concurrent design, in which attachment style, intimacy in the current romantic relationship, and psychological distress were assessed simultaneously, rules out causal inferences. The results would be strengthened by longitudinal studies assessing the extent to which insecure attachment is an antecedent, concomitant, or consequent of adverse functioning in attachment relationships (see, for instance, Feeney, Noller & Callan, 1994; Laible & Thompson, 2000). Despite these limitations, the present study builds on previous research by exploring the mechanisms through which insecure attachment may lead to the development of psychological distress. Although attachment theory predicts that people who have unsatisfactory early experiences with parents experience difficulty establishing affectional bonds in later life, hardly anything is known about the interpersonal mechanisms that may be involved. As Birtchnell (1993, p. 336) points out: ‘Do people who were denied close involvements lack the capacity to form them, manifest an excessive later need for them, form only insecure and untrusting ones, or avoid them altogether? Do they select partners who resemble the frustrating parent or who are quite different; or do they perceive and relate to everyone as though they were the frustrating parent?’ Future research would benefit from the recognition of the complexity of the link between attachment, intimacy in relationships, and psychological distress. Identifying the specific behavioural patterns through which insecurely attached individuals 100 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample develop less satisfying intimate relationships, and consequently psychological distress, would not only contribute to our basic knowledge of attachment, it might ultimately be useful for the development of counselling techniques that would allow insecurely attached individuals to enjoy more satisfying and intimate relationships. 101 Adult attachment, Intimacy and Psychological Distress in a Clinical and Community Sample 102

© Copyright 2026