Teachers' in-service training needs in a sample of aided Title

Title

Author(s)

Teachers' in-service training needs in a sample of aided

secondary schools in Hong Kong: the implication

forschool administration

Kan, Lai-fong, Flora.; 簡麗芳.

Citation

Issue Date

URL

Rights

1987

http://hdl.handle.net/10722/51394

The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent

rights) and the right to use in future works.

-5

-5--

SS

_S_S

-

-

S-5

S.'

,/55

\

\-

-

p-_.-

S.S

:- -

.

- ___-.

-

-

55_SS

- -' -

-

--5-'S.

S

'S

-S5 -'

-_'-

s_-s

-.

S

-

SS

S

-

sS

S....

s

-

- -

-

- -

-5_SS

-

............

S-5

S

555-5

-05'-S-5.

y..-

-_

-

..

i:

'-:-

-.

5

SS__-

5.-

.

--S- --

.5.

5.55.,

_

j

._s

..

.

-

.

-

5_S

5_s

-

.5

5

55_S-

5_S

5-

:<'.:

SS_-SS

-

-S

'/-'VV

S---

- S__ 5S_

_\

S'

-

-_

- SS-5

5

'S_._5555SS_SS.___:S,S555 'SS.

...... SS-..-

- -

5-

5

__.

SS

-

.

.

-_

ThE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG

EDUCATION LIBRARY

Deposited by the Author

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ABSTRACT

..............................

CHAPTER I

....................

Background to the Study ................

In-Service Teacher Training and School Development

Statement of the Problem

..............

Purpose of the Study

................

Hypotheses

......................

Organization of the Dissertation

..........

Definition of Terms ..................

INTRODUCTION

.

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

..............

Introduction

....................

Definition ......................

Importance and Purpose of In-service Teacher

Training ......................

Teachers' In-service Training Needs ..........

Content of In-service Programmes and Delivery

....................

Machanism

Need Assessment ....................

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

........................

....................

Introduction

................

Designand Procedure

......................

Sample

..................

The Questionnaire

METHOD

i

i

8

9

il

11

12

13

14

14

14

16

21

24

29

31

31

31

34

The Pilot Study ....................

35

37

Data Gathering and Analysis ..............

Limitation of the Study ................

37

38

CHAPTER IV

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

39

.

....................

..............

Introduction

Description of Respondents

Teachers In-service Training Needs as Perceived

by Teachers and Principals in Selected Areas of

Professional Skills and Knowledge

........

Perceptions of Teachers on the 46 Items of Training

Needs

Perceptions of Principals on the 46 Items of

Training Needs

Analysing Respondents' Perceptions of Needs on the

Eleven Clusters

Perceptions of Purpose of Teacher Training

Teachers' Perceptions of Training Purposes

Principals' Perceptions of Training Purposes

Perceptions of Training Time

Hypotheses Testing

......................

..................

..................

86

....................

..............

Conclusions ......................

Recommendations ....................

APPENDIX 2

50

......

SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

.

Introduction

Summary of Major Findings

APPENDIX 1

45

............

..................

.

APPENDICES

45

65

71

72

72

72

74

......

......

CHAPTER V

39

39

............................

..............

Letter to Participants

................

THE Questionnaires

86

88

95

96

101

102

106

APPENDIX 3

T-Tests Table: Perceptions of Training Needs

.

.

122

APPENDIX 4

T-Tests Table: Purpose of Teacher Training

.

.

127

APPENDIX 5

Anova Table ....................

128

APPENDIX 6

Frequency Distribution Tables

..........

131

BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................

139

-1-

ABSTRACT

II:1&i1

This study examines some issues and practices regarding the

professional development of in-service teachers in a sample of aided

secondary schools in Hong Kong.

Specifically, the study attempts to

identify the in-service training needs of teachers in selected areas of

professional skills and knowledge as perceived by teachers and

principals.

Related issues like the perceived best ways of learning,

purposes of in-service teacher training and time of day teachers should

participate in training activities are also investigated.

OI*1Ik1

In this study, thirty aided secondary schools were selected to

comprise the sample.

Responses used in this research were obtained from

30 principals and 60 teachers.

The instrument consists of 46 items

representing varieties of professional skills and knowledge and focuses

upon

eleven

major categories:

(1)

planning skills

(2)

instructional/communication skills (3) implementation of media (4)

classroom/pupil management skills (5) evaluation (6) special needs skills

(7) interpersonal skills (8) extra-curricular skill s (9) administrative

skills (10) knowledge of the educational system (11) knowledge of the

theoretical foundations of educational practice.

MAJOR FINDINGS

In general, teachers and principals in this study perceived teachers

need moderate amount of training in all 46 items of corapetencies.

- 11 -

Teachers and principals identified skills related to 1counselling

as the greatest priority of needs while they perceived the least needs in

coinpetencies associated with presenting ideas in Chinese.

In regard to the ordering of in-service needs in terms of clusters'

overall importance,

principals did.

Principals,

skills'

'special needs

training.

teachers rated 'extra-curricular skills' higher than

slightly different from teachers, perceived

Both groups considered

needed training cluster.

skills teachers need

'interpersonal skills' as the least

as the most important

With respect to the degree of training needs in

all 46 items of competencies, principals rated all items somewhat higher

than teachers did.

consideration,

When purposes of teacher training are taken into

teachers tended to place higher priorities on individual

interests while principals/concerned more with school development.

Principals and teachers held similar ideas regarding the best ways

of acquiring all competencies.

Training courses provided by various

organizations were the most preferred way of learning, followed by

programmes offered by local universities and school-based training

activities.

Self-study programme

way of learning.

was considered as the least preferred

Both groups also perceived teachers should spend their

own time to participate in in-service training activities and weekends

were considered the most suitable time for teachers to update their

skills and knowledge.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

In-service teacher training is a very important activity by which

teachers skills and knowledge could be continually enhanced so that they

can educate children more effectively.

It has been recognized, however,

by many educators that the most effective and beneficial in-service

activities are those originating from the real needs of teachers to be

served.

Report by a Visiting Panel (1982, p.94) pointed out: "the most

common criticizms of in-service programmes which we heard from teachers

were: failure of the activities to meet the perceived needs of classroom

practitioners..."

This study is an attempt to identify teachers' in-service training

needs in a sample of aided secondary schools in Hong Kong.

Presently

this is a crucial issue particularly in a society which is developing

rapidly and in great need for well qualified teachers to upgrade the

quali,f'y of education.

As Judith Christensen (1981, p.81) said: "In any

rapidly changing society, the schools are often asked to be a vehicle for

assimilating and transmitting changes.

respond to the demands on skills,

Therefore, to help teachers

it is important to examine what

teachers' needs are."

Overthe past decade, expansion in secondary education in Hong Kong

has been tremendous.

In 17O, the provision of subsidized secondary

education was stepped up to 50% to the Forms I-III age group.

In 1974, a

White Paper affirmed the ultimate objective of a place for all children

of the appropriate age who qualified for and wanted a secondary school

education.

Eventually in 1978 universal free junior secondary education

was introduced.

In the provision of subsidized senior secondary

Page 2

educati on, the 1978 Whi te Paper poi nted out a major target of

quantitative improvement from 60% of the 15-year-old population in 1980

to more than 70% by 1986.

The continuing increase in pupil enrollment

According to the

inevitably requires an increase in number of teachers.

annual summary of the Education Department, the number of aided secondary

school teachers has been increasing rapidly.

Table 1:

Growth in the Number of Aided Secondary Schools, Pupils, and

Teachers in Hong Kong form 1963 to 1985.

Year

*No of Aided

Secondary Schools

No. of Pupils

No. of Teachers

1963

39

18,826

1,054

1968

60

36,753

1,549

1973

91

60,559

2,500

1978

129

99,027

4,194

1983

263

243,778

10,730

1985

276

251,529

12,181

Sources:

Education Department: Annual Summary 1963-1986

*include day secondary non-certificate of ed., secondary certificate of

ed.-grarnmar, secondary certificate of ed.-technical and vocational

Despite prodigious progress in the quantitative aspect of secondary

education in Hong Kong,

desired.

the qualitative aspect remains much to be

To this fact, the report by a Visiting Panel pointed out: "we

are convinced that comments about falling standards are really a

reflection of the rapid increase in participation rates...

Most of the

schools, however, leave something to be desired.

Facilities, teacher

qualifications, examination results and other indicators of quality rank

low." (1982, p.58)

The expansion in secondary education has intensified the need for

in-service teacher training.

A Visiting Panel indicated one feasible way

to upgrade the quality ofeducation: "Levelling-up could also focus on

improving teachers.

Schools with large numbers of minimally qualified

teachers could be provided with supplementary resources for in-service

training and for the opportunity for some staff to return to college or

university for an upgrading programme." (1982, p.59)

Teacher Training is directed towards obtaining better achievement

for the pupils and in turn, for the well-being of the whole society.

With respect to the provision of in-service teacher training courses,

formal qualification bearing courses at the graudate level are provided

by the two universities; non-graduate teachers are trained by the three

colleges of education (Northcote, Grantham and Sir Robert Black) and the

Hong Kong Technical Teachers' College.

Informal non-qualification

bearing in-service teacher training courses are provided by various

organizations.

For example, the Advisory Inspectorate and the Training

Unit under the administration of the Education Department, Department of

extra-mural studies in the two universities and Baptist College, various

teacher associations, individual schools etc.

They provide different

types of in-service training courses for teachers,

ranging from

workshops, seminars, lectures to conferences with different duration.

In fact, in-service teacher training has been receiving government's

attention since 1963 (the issue was first addressed by the Education

Commission).

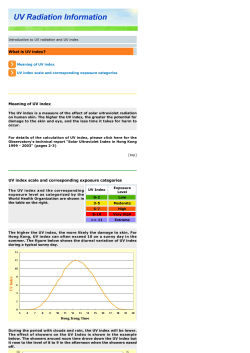

The quantitative expansion as shown in graph i well

illustrates this point.

It is worth noting that the number of trained

graduate teacher has increased from 32.8% in 1963 to 60.7% in 1986 and

Page 4

trained non-graduate teachers from 60.6% in 1963 to 81.9% in 1986

However, quantitative expansion in teacher training should be accompanied

by qualitative improvement so that teachers are able to respond

positively to changes imposed on them from the school setting or from the

community at large.

To this fact, the identification of teachers'

perceived in-service training needs is crucial and necessary as far as

improvement of the quality of education is concerned.

Page 5

Number of

teacher

Graph 1: Profile of Teacher Training in Hong Kong

(X 7006)

46

'f4

42

33

40

38

r

36

34

32

30

26

2+

22

L. C a tia I

20

-----------:6 -----

___1--

la

Trained non graudate teacher

61 1%

16

8%

14

35* 3%

12

32. 5%

10

60.6%

8

--

6

f

4

49.2%

--

Trajnedgraduateteacher-

---**--

2

28.8%

32.8%

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

7

71

72

73

74

is

76

17 ia

79

o

ai

a 83

84

Year

Adopted from Y.C. Cheng:

Function and Effectiveness of Education pg.39'f; being updated.

85

8

There are also a number of government reports which illustrate the

policy and planning of the government concerning in-service teacher

training in Hong Kong.

Report

Policy and Planning of In-service Teacher Training

1963 Report of

Education

Commission

Refresher courses for practising teachers and for

head teachers and those aspiring to promotion need,

co-ordination and development

1973 Green Paper

Report of the

Board of

Education on the

proposed

expansion of

secondary

education over

the next decade

- There should be regular review of policy regarding

professional training for graduate teachers

* The two universities should give serious

consideration to a greater expansion of their

graduate teacher education facilities

- Suitably constituted machinery should be

established under the auspices of the Board of

Education to study, and make recommendation on

all aspects of teacher education in Hong Kong.

1974 White

Paper: Secondary

education in

Hong Kong over

the next decade

In the face of expansion and improvement of

secondary education, teacher training should be well

planned.

1977 Green

Paper: Senior

secondary and

tertiary

education:- a

development

programme for

Hong Kong over

the next decade

- A systematic programme will be developed for the

in-service retraining of teachers who have been

some years in the schools.

- University graduates who enter the teaching

profession should take a course of teacher

1978 White

Paper: the

development of

senior and

tertiary

education

- New graduate entrants to the aided sector should

be required to undertake a course of teacher

training before they would be eligible for

promotion, as is already required in the

government sector.

- Introduce regular courses of refresher training

for serving teacher.

training.

Page 7

Report

Policy and Planning of In-service Teacher Training

1982 A

perspective on

education in

Hong Kong:

Report by a

visiting panel

- Formulate and publish a phase-in plan for

providing adequate in-service upgrading

opportunities for existing teachers.

- Improve the co-ordination mechanism of teacher

1984 Education

Commission

Report No. i

- Focus on non-graduate teacher training.

- Provide a new college of education to strengthen

both the quality and quantity of teacher

preparation.

- Set up regional teachers' centre to encourage

exchange of experiences, to promote continuous

professional development and enrichment and to

foster among teachers a greater sense of unity.

1986 Education

Commission

Report No. 2

- Expand part-time in-service training for

graduate teacher to 80% by 1994.

- In-service training for teachers of children with

special education needs be implemented in the

stages in 1987 and 1990 respectively.

training.

- Teachers in school should have an influential role

alongside college and university faculty. . . in

identifying in-service and pre-service needs and

in formulating means of meeting them.

The policy papers cited bear several characteristics.

Firstly,

in-

service teacher training is crucial for upgrading the quality of

education particularly in the face of rapid educational expansion.

Secondly, in-service teacher training programmes should be well coordinated to meet the perceived needs of practising teachers.

Thirdly,

in-service teacher training plays a crucial role to enhance teachers'

professionalism.

However, policy makers and educators tend to pay much

emphasis on the quantitative expansion of in-service training activities,

less attention is drawn to the crucial issues of the content of inservice programmes as well as effectiveness of such programmes.

For the

most beneficial and effective in-service training, needs assessment of

practising teachers should be conducted and programmes should be planned

Page 8

according to their perceived needs rather than being dictated by the

external agencs who are mostly removed from the practical classroom

experience.

IN-SERVICE TEACHER TRAINING AND SCHOOL DEVELOPMENT

In the school context, in-service teacher training has been closely

related with staff development programmes which contributes towards the

growth and improvement of the organization of which teachers are a part.

School administrators, responsible for organizational development, must

concern themselves with professional development of teachers so that

interests of the individual staff member and organization can be served.

"As a resource manager, he or she must work with and through people to

accomplish the purposes of the organizatíon.

(Knezevich, 1975, p.79)

Schools are part of the broader community, in the face of changing

circumstances in society, new problems and concerns emerge.

about the needs and perceptions of teachers are vital.

New data

Success in school

improvement, as pointed out by Neals et al: "depends on the availability

to school personnel of training opportunities specifically related to

changes being introduced..." (1981,

P.

197)

If human resources, the

staff of the organization, are critical for improvement, then their

perceived needs for in-service training is vital.

It has been recognized

that successful staff development depends on whether the programme has a

high possibility of meeting

teachers1

felt needs rather than as a given

prescription telling teachers what they ought to do.

As what Neale

Bailey and Ross (1981, P.63) pointed out: I*the extent to which individual

needs are satisfied within an organization has a crucial effect on the

morale and the productivity of individuals."

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

This research is an attempt to investigate the needs of a sample of

aided secondary school teachers for in-service training as perceived by

them and by the principals.

The responsibility of a secondary school teacher in Hong Kong is

both difficult and complex.

He or she deals with the development of

human minds and skills, and the translation of the society's morals and

values.

Their contribution to education is particularly crucial in this

critical transitional period to 1997 when Hong Kong becomes a Special

Administrative Region of the Peopl&s Republic of China.

Therefore,

to

enhance teaching effectiveness, not only do teachers need upgrading their

skills and knowledge but educational planners and school administrators

should also investigate the kinds of in-service training needs perceived

by teachers so that planning for in-service teacher training and staff

development can be done more effectively.

In Hong Kong, the initial preparation of teachers is inadequate to

cope with social and technological changes.

Therefore teachers now in

service need to acquire more skills and keep abreast of new developments

and changes in this field.

Rubin emphasized that:

"The professional development of teachers now in

service seems to be a central element for reforms in

education....

It is the teacher al ready i n the

school who must serve as the agent of reform.

Since

practitioners rarely adapt instantly to an

innovation, the evaluation of teaching must go hand

in hand with new developments in the process of

education." (1974, p.4)

Indeed, all along, the government has been stressing the importance of

in-service teacher training as cited in the various educational reports

earlier in this chapter.

However, it is only the report by a Visiting

Panel that has correctly pointed out the fatal criticism of in-service

programmes: they failed to meet the perceived needs of serving teachers.

Page 10

For maxima' effectiveness, p'anning for in-service programmes should

be based on comprehensive studies of the real needs perceived by teachers

and by those who are in immediate contact with them, such as principals,

rather than by the providing agencies since they might not be in a good

position to dictate what programmes would be best.

It is the teachers

and principals who face the challenges inside and outside the schools; it

is their responsibilities in educating the young, implementing the

curriculum and enforcing the reforms.

An investigation of teachers' in-service training needs in aided

secondary schools in Hong Kong is very much needed.

Firstly, a needs

assessment for in-service teacher training has not been conducted by the

government.

Secondly, a survey on in-service activities conducted by the

Hong Kong Association for Science and Mathematics Education Limited

(HKASME) in 1984 was confined to school-based and to members of the

association (only science and mathematics teachers).

Thirdly, a local

project on Teacher Induction and Development (TIAD) is presently carrying

out by Professor Cooke, B.L. and Pang, K.C. of the University of Hong

Kong.

In the first phase,

this project mainly investigates the

experiences and needs of beginning teachers.

It would be both necessary

and valuable if training needs of teachers, other than their first year

of service, can also be identified at the present time.

Therefore, in

the face of changing circumstances in society and schools, a better

understanding of the nature and extent of the needs of in-service

teachers is definitely valuable for educational planners and school

administrators to plan, co-ordinate and implement comprehensive inservice programmes for teachers.

Page 11

PURPOSES OF THE STUDY

The purposes of the study are as foflows:(1)

To identify teachers' in-service training needs as perceived by

teachers and principals in selected areas of professional knowledge

and skills.

(2)

To identify the relative importance principals and teachers give to

different areas of professional knowledge and skills.

(3)

To identify the effects of various variables such as year of

teaching experience, level of education, professional qualification,

age of school, subjects taught and post held in school on the

perceptions of teachers' in-service training needs in selected areas

of professional knowledge and skills.

(4)

To identify how principals and teachers rate the different purposes

of in-service teacher training.

(5)

To identify what principals and teachers perceived as best ways to

acquire selected areas of professional skills and knowledge.

(6)

To identify what principals and teachers perceived as the most

suitable time teachers should participate in in-service teacher

training activittes.

WVDTU

(1)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

andprincïpals in regard to teachers' in-service training needs in

selected areas of professional knowledge and skills.

(2)

There are no significant differences in the perception of principals

and teachers in regard to purposes of teacher training.

(3)

There are no significant differences among teachers with different

pre-service qualifications in regard to their perceptions of

teachers' in-service training needs in selected areas of

Page 12

professional knowledge and skills.

(4)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

with various degrees of experience in regard to teachers' in-service

training needs in selected areas of professional

skills and

knowledge.

(5)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

with different ranks in regard to teachers' in-service training

needs in selected areas of professional knowledge and skills.

(6)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

with different subjects to teach in regard to teachers' in-service

training needs in selected areas of professional knowledge and

skills.

(7)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

who work in sols with different years of establishment in regard

to

teachers' in-service training needs

in selected areas of

professional knowledge and skills.

(8)

There are no significant differences in the perception of teachers

who had Cert.Ed./Dip.Ed.

and those who had not in regard to

teachers' in-service training needs in

ected areas of professional

knowledge and skills.

ORGANIZATION OF THE DISSERTATION

The remainder of this dissertation consists of four chapters.

Chaper II is devoted to the review of the literature on in-service

teacher training, including an overview of definition, the importance and

purposes of in-service teacher training, teachers' in-service training

needs, content of in-service programmes and delivery mechanism, and needs

assessment.

Chapter III describes the methodology and procedures

Page 13

utilized in this study, including the sampling selection, questionnaire

design,

research.

data collection, treatment of data and limitation of the

Results of the study are reported in Chapter IV.

study is summarized in Chaper V.

Finally, the

Also, this chapter concludes the study

and includes recommendations for improvement of in-service teacher

training in Hong Kong, and recommendation for further research.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

For clarity of interpretation, the following terms which will be

used in this study are defined.

In-service teacher training - in-service teacher training will be used as

a synonym with in-service teacher education and in-service education

and training of teachers

(INSET).

interchangable in this study.

The three terms will

be

The definition put forth by Bol am

(1980, p.3) is most appropriate for this study: "Those education and

training activities engaged in by primary and secondary school

teachers and principals, following their initial professional

certification, and intended mainly or exclusively to improve the

professional knowledge, skills and attitudes in order that they can

educate children more effectively."

Need

- the discrepancy between "What is" and "What ought to be", or

between the existing situation and the desired outcomes.

Page 14

N41IDTI1

TI

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

INTRODUCTION

In-service teacher training has long been considered by educators as

an important vehicle to upgrade the quality of education.

Because of the

importance of the topic, the literature on in-service teacher training is

very ample and still growing.

As Wells (1978, p.16) maintained, the

vastness of in-service education made the task of reviewing the

literature on the subject a difficult one.

For the purpose of this

study, the following areas will be dealt with concisely:

(1)

Definition

(2)

Importance and purpose of in-service teacher training

(3)

Teachers

(4)

Content of in-service programmes and delivery mechanism

(5)

Needs assessment

in-service training needs

DEFINITION

Hass (1957, p.13) maintained that in-service training included all

activities engaged in by professional personnel during their service and

designed to contribute to improvement on the job.

conceptualization of the term 'in-service training'.

This is a broad

In the same vein,

Harris and Bessent (1969, p.2) declared that in-service training must

include all activities aimed at the improvement of professional staff

members.

Later, Harris tried to narrow the term in-service training to

mean:

Any planned programme of learning opportunities

afforded staff members of schools, colleges, or

other educational agencies for purpose of improving

the performance of the individual in already

assigned positions. (1980,

P.21)

Page 15

According to Harris, a planned programme is specified to contribute

to

the purposes of in-service training.

In prescribing planned

programmes, then one of the most important emphases is placed on

assessing needs.

Freidman et al

programme as a planned,

.

(1980,

P.162) defined in-service

co-ordinated series of activities which

contribute to professional development.

The preceding definitions deal mostly with in-service training in

general.

Since this study deals with the professional development of

practising teachers in schools, it is necessary to consider some of those

definitions pertinent to the task.

In the United Kingdom, the Department of Education and Science

(1970) has defined in-service training as "any activities which a teacher

undertakes after he had begun to teach, which is concerned with his

professional

workt1.

(Henderson,

1978,

p.11)

There is also narrower definition of in-service training such as

that described by the United States Department of Health,

Education and

Welfare (1965):

A programme of systematized activities promoted or

directed by the school system, or approved by the

school system, that contribute to the professional

or occupational growth and competence of staff

members during the time of their service to the

school system.

(Henderson,

1978, p.11)

There are two definitions that seem more appropriate and suitable

for thi s study.

Firstly, Orrange P.A. and Van Ryn M. gave the

definition:

In-service education is that portion of professional

development that should be publicly supported and

included a programme of systematically designed

activities planned to increase the competencies knowledge, skills, and attitudes - needed by school

personnel in the performance of theïr assigned

responsi bi i

ties.

(1975, p.47)

Page 16

Secondly, Bolam R. defined in-service education and training of

teacher as:

Those primary and secondary school teachers and

principals, following their initial professional

certification, and intended mainly or exclusively to

improve theirprofessional knowledge, skills, and

attitudes in order that they can educate children

more effectively.

(1980,

P.3)

Therefore, in this study, in-service teacher training is more

appropriately defined as those activities characterized by:

(1)

Design for teachers who have obtained their initial professional

certification.

(2)

Programmes are systematically planned to meet the perceived needs of

serving teachers.

(3)

Continuing education is directed towards individual professional

development and system (e.g.

school) development.

IMPORTANCE AND PURPOSE OF IN-SERVICE TEACHER TRAINING

In-service training is very essential for the professional

development of the practitioners in all fields.

It is even more

important for those who are involved with education of the young in

schools.

Harris and Bessent (1969, p.3-4) gave four reasons for the

importance of in-service training:

(1)

Pre-service preparation of professional staff members is rarely

ideal and may be primarily an

introduction to professional

preparation, rather than professional preparation as such.

(2)

Social and educational change makes current professional practices

obsolete or relatively ineffective in a very short period of time.

This applies to methods and techniques, tools and substantive

knowledge itself.

Page 17

(3)

Co-ordination and articulation of instructional practices requires

changes in people.

Even when each instructional staff rnetnber is

functioning at a highly professional level, employing an optimum

number of the most effective practices such as instructional

programme, might still be relatively un-coordinated from subject to

subject and poorly articulated from year to year.

(4)

Other factors argue for in-service education activities of rather

diverse kinds.

Morale can be stimulated and maintained through in-

service education,

and is a contribution to instruction in itself,

even if instructional improvement of any dynamic kind does not

occur.

According to Hass (1957, pJ4) there are a number of factors which

make clear the need for in-service training:

(1)

The continuing cultural and social changes which create need for

curricul um change.

(2)

Pre-service education cannot adequately prepare members of the

public school professional staff for their responsibilities.

(3)

Increase in pupil enrollment.

(4)

The present and continuing increase in the number of teachers.

(5)

The present and continuing shortages of adequately prepared

teachers.

(6)

The present and continuing need for improved school leaders.

The six points raised by Hass are most applicable to Hong Kong and

also justify the expansion of in-service teacher training in recent

years.

A British government committee, the Advisory Committee on the Supply

and Training of teachers (ACSTT 1974) suggested that the aims of INSET

are to enable teachers:

(1)

To develop their professional competence, confidence, and relevant

knowledge.

(2)

To evaluate their own work and attitudes in conjunction with their

professional colleagues in other parts of the education service.

(3)

To develop criteria which would help them to assess their own

teaching roles in relation to a changing society for which schools

must equip their pupils.

(4)

To advance their careers.

Though the ultimate goal of in-service teacher training is to

enhance teachers' skills, knowledge and attitude so that they can educate

pupils more effectively, it is also for the purposes of individual

development and school development that in-service teacher training sets

its value.

Bolam (1982,

p.11) in his final report on INSET distinguished

between five main purposes of continuing education for teachers:

(1)

Improving the job performance skills of the whole school staff or of

groups of staff (e.g. a school focused INSET programme).

(2)

Improving the job peformance skills of an individual teacher (e.g.

an induction programme for a beginning teacher).

(3)

Extending the experience of an individual teacher for career

development or promotion purposes (e.g. a leadership training

course).

(4)

Developing the professional knowledge and understanding of an

individual teacher (e.g.

(5)

a Masters degree in educational studies).

Extending the personal or general education of an individual (e.g. a

Masterts degree course not in education or a subject related to

teaching).

However, it has been recognized that in all organizations the

problem lies in the conflict between meeting the requirements and goals

of the organization and of satisfying the needs for self-fulfilments of

Page 19

the individual member of an organization.

Getzels and Guba (1957, p.423-

441) related this problem to the five purposes of continuing education

for teachers.

Table

System and Individual Need Factors and the Purposes of

1:

Continuing Education

>

System

.- Requirement

Individual Needs

Purpose 1:

Staff/Group

Performance

In

Purpose 2:

Individual

Job

Performance

table

Purpose 3:

Career

Development

Purpose 4:

Professional

knowledge

Purpose 5:

Personal

Education

1, while purpose i satisfies more the requirement of the

system than meets individual needs, purpose S is just the reverse.

According to Bolani (1982, p.12), the diagram illustrates Henderson's

(1979) point that a useful distinction can be made between the main and

incidental purposes and outcomes of an

INSET activity.

The Final Report

of Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) Project on

INSET, OECD, indicated the different perceptions of purposes of

can be summarized in the following table:

INSET and

Table 2:

Different Perceptions of Purposes of INSET, CERI, OECD

INSET Purpose

Purpose

Purpose

Purpose

Purpose

Purpose

i

2

3

4

5

+

o

o

4)

o

,

.

,

o

rø

u-o

>0

rl-4

4-o

1-4

4-)

.4

G)

)

.4

)

c,)4

Source

of

Support

o

0

E

4

o

u)

00

c

O

O.)

L)

Teacher

Principal

Teacher

Principal

All

All

Teacher

Universities

Professional

Association

Universities

Professional

Assocíation

INSET

purpose

as

viewed

from

OECD

member

Many

Many

A few

coun-

tries

In-service teacher training has been conceived as an important

vehicle to enhance staff development.

efcei

INSET,

For the most beneficial and

interests of both the individual staff member and the

organization must be taken into consideration in order to avoid conflict.

In summary, review of the literature on importance and purpose of

in-service teacher training highlights the beliefs that it has the

potential for stimulating professional development of teachers, enhancing

school development, and may assist in implementing social change.

Page 21

TEACHERS' IN-SERVICE TRAINING NEEDS

Many researchers have addressed themselves to the important question

of teachers' in-service training needs.

While sorne educators have

identified a number of typical training needs of teachers, others survey

self-reported needs in relation, for instance,

to the teaching of

particular subjects and to the management of schools.

In another aspect,

a lot of research projects have been carried out to study teachers' needs

at different career stages.

In 1957, Hass (p.21) identified some typical

training needs of teachers, summarized below:

(1)

Maintenance of familiarity with new knowledge and subject matter.

(2)

Human growth and learning.

(3)

Improved knowledge of teaching methods.

(4)

Increased skill in providing for the individual differences among

students.

(5)

Improved attitudes and skills involved in cooperative action

research.

(6)

Greater skills in using resources and in working with adults.

(7)

How to learn a new job.

(8)

The development and refinement of common values and goals.

(9)

The building of professionalism and high morale.

Apparently, Hass was more in concern with those training needs

directly related to classroom teaching.

In

the United Kingdom, the National Foundation for Educational

Research completed a study called 'In-service Training - A study of

Teachers' Views and Preferences.'

The study was reported by Brian Cane

in a volume published by the Foundation in 1969.

An important part of

the survey was concerned with establishing the topics that teachers

considered should form the content of future in-service training

programmes.

The following nine topics were listed as the most needed

Page 22

topics by teachers:

(1)

(p.21)

Learning difficulties that any child might have, and methods of

dealing with them.

(2)

Pros and cons of new methods of school/class organization.

(3)

Operation and application of new apparatus and equipment, with

practice opportunities.

(4)

Start courses on most recent findings of educational research in

teachers' areas of teaching.

(5)

Planning and developing syllabi in detail so that content relevant

to the most child are arranged in teachable units.

(6)

Description and demonstration of methods of teaching tacademic'

subjects to 'non-academic' children.

(7)

Methods of dealing with large classes of varied abilities with

little equipment or space.

(8)

Practical details and aims of recently introduced schemes of work

and discussion of teaching results and demonstrations.

(9)

Construction,

marking and interpretation of school exams and

assessment tests.

The nine topics all dealt with professional skills and knowledge.

They included: planning skills, implementation of media, classroom

management skills, evaluation, and special needs skills.

In studying the perceptions of elementary teachers professional

concerns and in-service needs, Wells (1q78, p.99) identified the top

priorities for in-service education topics as seen by each professional

group.

They were:

Superintendents

- Individualizing instruction

Motivation of pupils

Metric education

Classroom management

Page 23

In-service Coordinators - Individualizing instruction

Teaching reading

Utilization of test data

Motivation of pupils

Teachers

- Individualizing Instruction

Slow learners in the classroom

Motivatftn of pupils

Effective teaching and learning were the prime concern of each group

which indicated they paid more attention to job-specific needs for inservice teacher training.

The Final Report of CERI Project on INSET, OECD (1982, p.18) quoted

Fullers (1970) in-service training needs of teachers in relation to

career development.

I

II

Early phase

O Concerns about self (non-teaching concern)

Middle phase

i Concerns about professional expectations and

acceptance.

2 Concerns about one's own adequancy: subject matter

and class control.

3 Concerns about relationships with pupils.

III Late phase

4 Concerns about pupils learning what is taught.

5 Concerns about pupils' learning what they need.

6 Concerns about one's own (teacher's) contribution

to pupil change.

According to Fuller, throughout the middle and late phase of a

teacher's career,

in-service training is much needed in accordance with

his/her concerns.

Similarly, an attempt was made by a national committee for INSET in

England and Wales to devise an INSET needs framework based upon the

likely career patterns of teachers.

Report on INSET,

OECD (1982,p.18)

Table 3 is adapted from the final

Page 24

Table 3:

INSET Needs Framework in Relation to the Likely Career Patterns

of Teachers

Year of Teaching

INSET needs

Induction year

4 - 6

a consolidation period, during which teachers would

attend short, specific courses

6 - 8

a reorientation period which could involve

a secondent for a one term course and a change in

career development

8 - 12

a period of further studies, in advanced seminars

to develop specialist expertise

12 - 15

at about mid-career, some teachers would benefit

from advanced studies programmes of one year or

more in length, possibly to equip them for

leadership

a minority would need preparation for top

After mid-career

management roles while the majority would need

regular opportunities for refreshment

The literature on teachers' in-service training needs indicates

teachers in-service needs are great and varied.

While some educators

identify a list of typical in-service needs, other researchers suggest

job development and career patterns be used as yardsticks to measure

teachersin-service training needs.

effective and beneficial,

In order to make INSET more

in-service teacher training programmes should

be planned in response to assessed needs.

CONTENT OF IN-SERVICE PROGRAMMES AND DELIVERY MECHANISM

Edefelt (1981, p.115) in his observation of in-service progress over

the past six years, contended that "niost programmes are short-term.

They

Page 25

usually address specific problems (mainstrearning, multicultural and/or

bilingual education, teacher stress and burnout, improving basic skills,

etc.)

Very often they are three-hour, one-shot activities.

Teachers get

together to learn the use of manipulative materials in Mathematics, a new

approach to discipline, or better ways to make and use tests.

In 1967 Ashers research suggested that the content of in-service

programmes should concentrate on four areas: information gathering,

attitude change, self-improvement, and skill training.

Nicholson's research (1976, p.15-20) of in-servi ce education

revealed that in-service programmes had focused on five areas:

(1)

Job-embedded, in which in-service programmes are directed to

teacher's immediate needs in their current teaching positions.

(2)

Job-related, in which in-service programmes are closely related to

the job, but does not take place while teaching is going on.

For

example, a team of teachers can take an after-school workshop on

team teaching.

(3)

Credential-oriented, in which in-service emphases are placed on

meeting teachers' needs for certificates or professional

advancement.

(4)

Professional organization related, in which programmes generally

have one of the two purposes: they are channeled towards teachers'

needs as members of a specific discipline or they focus on

teachers1

needs as employees of school systems.

(5)

Personal,

in which in-service activities facilitate personal

development which may or may not be job related.

According to Nicholson's research, in-service training programmes

are designed to meet individual needs as well as school needs.

In regard to in-service delivery system, Bolam (1982, p.26) in the

Page 26

Final Report of CERI Project on INSET, OECD, illustrated different INSET

courses in the limited kingdom as shown in Table 4.

Table 4:

School-Focused Inset Compared with Long and Short Courses

Long Course

Charateristics

Short Course

eg. (In-service);

e.g. 10 weekly sessions

at a teachers centre

on subject teaching

B.Ed,, Advanced

Dioloma, and M.Ed.

School-Focused

e.g. Day conference

and follow-up group

meetings

Aims

Individuai professional/

personal development

Individuai vocational

development

Group/School (Le. system)

development

Location

Centre (i.e. off-site)

Mainly centre

Mainly school (i.e. on

site)

Participants

Individual teachers from

different scnoois

Mainly individual teachers

from different schools

Individuals and groups

mainly from one school

Off-the-job/course

emoedded

Job related and sometimes

on-the-job! job-emoedded

J

Context

Off-the-job/course

emoeadea

Length

Up to 3 years

Up to 12 weeks

Usually short term

Staffing

Centre/external

Mainly centre/external

School and external

InitiatorfDesigner

Centre

Centre (usually)

School/Group/Teacher

Knowledge of theory,

research and suoject

discipline

General, practical,

knowledge and skills

Job specific, proolem-

Content

Typical methods

Lectures, tutorials and

discussion groups

Workshops, films and

simulations

School visits, classroom

observations and job

rotation

Accreditation/Awards

Yes

Sometimes

Very rarely

Follow-up

Rarely

Sometimes

Usually

Evaluation

Rarely

Sometimes

Sometimes

I

5oing, practical

knowledge and skills

Page 27

Edefelt (1975,

p.1) identified several types of in-service delivery

system, among them are: courses, workshops, seminars, curriculum

development projects, conferences, teacher centres and clinics,

sabbaticals, institutional visitings, educational travel, exchange

programmes, minicourses, micro-teachi ng, independent study, tutorial

sessions, simulations, role playing. videotaping and television lessons.

As to the dimension of time for in-service activities to take place,

the James Report (1972) recommended that all teachers might have some

entitlement to regular release for in-service education.

He suggested

one term every seven years leading eventually to one term every five

years.

According to the study by Copeland W. and Kingsford S. (1981, p.38)

"Most teachers clearly indicated that in-service training without release

time was totally ineffective because it occured after a full day's

teaching, thereby at a time when the energy level of the staff was at a

low point.

Research findings from Nicholson et al. (1976), McLaughlin and Marsh

(1978), and Yarget et al. (1980) have revealed that teachers prefer inservice activities conducted at schools,

related to the teachers

in school time, and be closely

responsibilities.

The James Report (DES, 1972,

Section 2.21) also recognized the importance of school-based in-service

teacher training: "In-service training should begin in the school.

It is

here that learning and teaching take place, curricula and techniques are

developed and needs and deficiencies revealed.

Every school should

regard the continued training of its teachers as an essential part of its

task, for which all members of staff share

responsibility.0

As a matter of fact, in many parts of the would, programmes have

been devised and put forward as a contribution to the development of

school-based in-service teacher training,

among the others,

the

Page 28

influential works include: the DES Regional Programme on School Centred

In-service Education, the OECD INSET Project and case studies of school-

based INSET collected in the world Yearbook of Education 1986.

The

findings revealed school-based in-service is the most effective teacher

training activity as far as needs of the individual teacher and school,

and evaluation of course are concerned.

on INSET, OECD (1982, p.59) stated:

The Final Report of CERI Project

niore effective INSET can be achieved

if teachers can contribute collaboratively to decisions about general

INSET policies and progranirnes at all stages - planning, implementation,

evaluation and follow-up.'

In this respect, school-based in-service is

the most feasible way to allow teacher participation in decision making

concerning training programmes.

Schmuck (1974, in David Hopkins ed. 1986, p.289) indicated: "Indeed,

organization development gains strengths as it is coupled with special

inservice education programmes."

Apparently school-based training

activities are more appropriately geared to needs of the school.

In regard to local examples, the INSET working party organized by

the Hong Kong Association for Science and Mathematics Education Limited

(HKASME) reported a few 1 ocal case studies on school based i n-service

teacher training, all of which demonstrate the practicability,

feasibílïty and effectiveness of school-based training programmes.

case study at Wu Chung College revealed (HKASP4E 1985,

A

p.82-83):

"definitely, INSET at the school level facilitated the development of our

school and its staff. This was especially important to a young school

such as ours."

Similarly, another case study carried out in

St.

Benedict's Secondary Technical School indicated (HKASME 1985, p.117):

"instead of teachers going on an in-service course, the course should go

to the teachers in their own school.

In fact, the idea of S-B INSET was

Page 29

acceptable to 72% of the respondents.

The literature on content of in-service programmes and delivery

mechanism indicates that teachers need continuous in-service training on

job-embedded and job-related areas such as knowledge of subject matters,

teaching skills and classroom management.

While teachers should be given

time release to attend in-service training courses, school-based training

is found to be the most effective in-service activity.

NEEDS ASSESSMENT

The major purpose of this study deals with teachers in-service

training needs in a sample of aided secondary schools in Hong Kong.

Specifically,

the objective is to determine in what areas of skills and

knowledge Hong Kong teachers need in-service training.

In order to reach

the goal of this endeavor, a needs assessment procedure will be utilized

mainly through the written format.

It is appropriate at this point to

examine the idea and procedures of the needs assessment concept.

The most common interpretation of the word 'needs

in needs

assessment is the discrepancy between 'what is' and 'what ought to be'

(Berne, 1976, p.4).

Sometimes, these needs are obvious and readily

observable; other times these needs are hidden and not able to be

perceived without fine instrumentation (Spitzer, 1979, p.4).

Therefore

needs assessment is a systematic procedure by which educational needs are

identified and ranked in order of priority.

Needs assessment is an

important element in educational planning particularly when it is

employed as

a continuous process - planning

- development -

implementation - evaluation - revision cycle of a programme. Berne

(1976, p.2) declared that if the needs assessment process is internalized

by the local school personnel, there are essentially no limits to the

benefits that can be derived.

Better planning, increased involvement,

and communication among different societal groups; better information for

decision making, more meaningful feedback and evaluation; closer

coordination; better definition of district, building, classroom and

individual goals; and much more could result from a 'properly' done needs

assessment.

The literature reveals that needs assessment procedures are

important for successful in-service programmes.

It should be an integral

component of a framework within which in-service programmes can be built

and modified to meet the perceived training needs of teachers.

rWI1DrEø TTT

INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes the procedures used in this study.

are discussions of the sample and sampling methods.

Included

Also described is

the instrument used in collecting the data - its construction and pilot

testing - the process of collecting the data and finally,

the data

analysis.

DESIGN AND PROCEDURE

This study is in the form of a descriptive survey.

The sample

consists of 30 principals and 60 teachers from 30 aided secondary schools

in Hong Kong.

It has been decided that the data will be collected

through postal questionnaire.

The rationale in the investigation of these principals and teachers

as the sample of the study are as follows:

(1)

Principals are in immediate contact with teachers, and are the ones

who may be expected to express the needs with accuracy.

A better

understanding of both principals and teachers perception of in-

service teacher training is certainly valuable to educational

planners and school administratíons to plan training programmes.

Programmes thus formulated can contribute to satisfying needs of the

individual teachers while meeting goals of the school.

(2)

Teachers are directly responsible for educating the young.

An

investigation of their perceived in-service training needs can

enhance the quality of education particularly in the face of

educational expansion.

The information is useful for school

administrators to arrange, organize and plan staff development

Page 32

activities.

(3)

With the limitation of time set for this study, it is impossible to

investigate all principals and teachers.

In order that the sample

is at a managable and reasonable size, the study has to be limited

to the sample of 30 aided secondary schools, excluding government

and private schools.

Since aided schools constitute more than 75%

of the secondary schools in Hong Kong, samples drawn from this type

of schools are more representative than government and private

schools.

On the other hand,

in regard to resources and

administration, both government and private schools are quite

different from aided schools.

As a result, teachers' in-service

training needs among the three types of schools might be totally

different.

Therefore in the present study, samples are only drawn

from aided secondary schools.

(4)

The study aims at finding out principals and teachers perceptions of

teachers

in-service training needs,

and does not intend to

generalize the results to all principals and teachers.

The rationale for the collection of data through using postal

questionnaire are as follows:

(1)

The postal questionnaire is the most feasible and convenient

instrument to collect data.

It is particularly appropriate in the

present research because the study is essentially fact-gathering,

counting a representative sample and makes inferences about the

population as a whole.

Data collected will contribute significantly

to the planning and designing of training activities.

questionnaire is probably the simplest and most

Therefore the

straightforward

instrument than other method of investigation.

(2)

With regard to cost, the postal questionnaire permits wide coverage

Page 33

of sample for minimum increase in expense.

The expense mainly

relates to processing and analysing data as well as the

required in the study,

rnateriaF

for example, printing or duplicating,

providing stamps and self-addressed envelopes for the return.

When

the researcher hopes to obtain more accurate data through covering a

much larger sample, only a modest increase in cost can bring about

the desired outcome.

(3)

The postal questionnaire affords wider geographic contact.

The

sample of aided secondary school principals and teachers can be

drawn throughout the territory.

Apparently,

the greater the

coverage, the more representative the sample would be; the larger

the sample, the greater validity and reliability the result would

become.

In fact, extensive coverage of sample is a unique advantage

of using postal questionnaire in the present study.

(4)

With respect to questions and answers, postal questionnaire permits

more considered answers when respondents identify teachers' inservice training needs in selected areas of professional knowledge

and skills.

With the absence of the influence of the interviewer,

greater uniformity can be achieved in the manner in which questions

are posed.

At the same time, respondents are given a sense of

privacy when answering the question.

This point is particularly

imporùnt in the present study since issues of teachers' in-service

training needs may lead to certain kinds of sensitivity on

individual

teachers and anonymous postal

questionnaires can

certainly lessen the psychological burden and embarrassment of the

respondents so that a higher response rate can be secured.

Page 34

rur CItAflI t

The sample consisted of 30 principals and 60 teachers from 30 aided

Schools were selected from three

secondary schools in Hong Kong.

sources:

(1)

Students of the Cert.Ed. course, 1986-1987, University of Hong Kong.

(2)

Students of the M.Ed. course, 1g86-1987, University of Hong Kong.

(3)

Randomly selected from the school list of Hong Kong Subsidized

Secondary Schools Council.

One principal, one non-graduate teacher and one graduate teacher

were drawn from each school,

principals and 60 teachers.

making up a total population of 30

Sample schools were classified in the

following tables:

Table 1:

Classification of Schools by Location

Location

Number of schools

Hong Kong Island

10

Kowloon

New Territories

Table 2:

6

14

Classification of Schools by Sex Type

Sex type of school

Number of schools

Boys

2

Girls

5

Co-education

23

Page 35

Table 3:

Classification of Schools by Age

Age of school

Number of schools

i - la years

12

11 - 30 years

11

over 30 years

7

I

THE QUESTIONNAIRE

Prior to the construction of the questionnaire, informal interviews

were held with a few aided secondary school principals and teachers to

solicit a realistic picture of teachers' in-service training needs in

Hong Kong.

References from the literature were also made before the

completion of the provisional draft of the questionnaire.

Related

references include: Survey of Teacher Education Objectives (Singapore

Journal of Education, March 1981), Needs Assessment Survery (Lincoln

Intermediate Unit No.

R.W.

12, New Oxford,

Pennsyl/van9,a, collected in Rebore

Personnel Administration in Education, 1982, p.184-186),

Identification of typical training needs by Hass (1957, p.21), In-service

Training - a study of teachers' views and preferences (National

Foundation for Educational Research, 1969),

In-service training needs of

teachers and career development by Fuller (1970) etc.

Two sets of questionnaires were designed, one for principals, the

other for teachers.

Other than the first section which required

different personal data,

(See Appendix 1)

the two sets of questionnaires were identical.

In the first section, questions were designed to

collect data regarding respondents' general characteristics.

Information

relating to respondents' gender, age, level of education, years of

Page Ja

experience, post hei d, serving school (sex type, age) and professional

training were collected as independent variables which tuight have had an

effect on the respondents perception of teachers' in-service training

In the second section, 46 items on selected areas of professional

needs.

skills and knowledge were constructed to identify the needs of aided

secondary school teachers for in-service training.

In the same section,

respondents were also asked to identify the best way to acquire such

skills

and knowledge.

Altogether there were eleven areas of skills and

knowledge listed.

skills - 5

(1)

Planning

(2)

Instructional/communication skills - 9 items.

(3)

Implementation of Media - 4 items.

(4)

Classroom /pupil management skills - 4 items.

(5)

Evaluation - 2 items

(6)

Special needs skills - 3 items.

(7)

Interpersonal

(8)

Extra-curricular skills - 3 items.

(9)

Administrative skills - 4 items.

items.

skills -

4 items.

(10)

Knowledge of the educational system - 4 items.

(11)

Knowledge of the theoretical foundations of educational practice 4 items.

Respondents were asked to indicate firstly the degree of needs for

in-service training in the specified areas on a Likert Scale (a 5-point

scale, "1" represented no training need, "5" represented much training

needs).

Secondly, they were also required to indicate, among the four

ways ("A" represented activities organized by staff in school,

"B"

represented in-service training programmes in a university,

"C"

represented courses/seminars/workshops/conferences organized by various

Page 37

organizations, "D" represented self-study programmes) the best way to

acquire such skills and knowledge.

In the final section, respondents

were asked to rank in order of importance, the different areas and

purposes of in-service teacher training.

Their perceptions of delivery

mechanism (time of participating in training activities) were also

enquired in the last two questions.

THE PILOT STUDY

A pilot study was conducted to test the reliability, validity and

feasibility of the questionnaire.

In particular, this pilot work

contributed to fruitful ideas such as the clarity of items,

questions,

sequence of

the applicability of skills and knowledge to teaching

practices in Hong Kong,

the approximate completion time etc.

The

questionnaires were distributed to two principals, two non-graduate

teachers and two graduate teachers, all serving in aided secondary

schools in Hong Kong.

The result of the pilot testing indicated that

problems existed in the following areas: the wordings of the questions,

the format and comprehensiveness of the questionnaire,

With

modifications and refinements, the finalized quesionnaire was then sent

off for the actual survey.

DATA GATHERING AND ANALYSIS

Two covering letters (see Appendix 2) were attached to each

questionnaire, explaining the purpose of the research and seeking cooperation.

A total of 150 sets of questionnaires were sent to 50 aided

secondary schools in Hong Kong.

For each school, the questionnaires were

distributed to the principal, one non-graduate teacher and one graduate

teacher.

In early April the questionnaires were sent out and follow-up

supplementary copies of questionnaires were sent out in mid-May.

The

Page 38

final returns were received by the last week of May with 62% response

rate.

Data collected for this study were first coded and translated into

computer programmes sheets before they were computed on a SPSS-X system

for data processing.

LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

When interpreting the findings of this study, the following points

should be taken into account.

(1)

The conclusion and recommendations appear in Chapter V are based on

results of survey response only.

(2)

Teachers

in-service training needs are identified according to the

perceptions of a sample of aided secondary schools principals and

teachers.

Although the findings may have applications to principals

and teachers in government and private schools, the conclusions were

not generalized to include the larger population.

(3)

Population sampling was a limitation since participants in the study

were mainly from students of the M.Ed. course.

CHAPTER IV

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

INTRODUCTION

The primary purpose of this research is the assessment of teachers

in-service training needs in a sample of aided secondary schools, by

identifying selected areas of professional skills and knowledge perceived

by teachers and principals, as important for continued professional

development.

In this chapter, findings are reported in six

sections.

The first

section describes the respondents who participated in the study in terms

of their distributions among the variables of gender, age, level of

education, years of experience, post held, and professional training.

The second section reports findings regarding the respondentts

perceptions of in-service training needs.

The third section reports

findings related to the respondents' perceptions of needs in the eleven

clusters.

Perceptions of the best ways to acquire selected areas of

professional skills and knowledge are reported in section four.

The

fifth section presents findings regarding respondents' perceptions of the

purposes of teacher training and time preference in participating in

training activities.

Differences between teachers and principals on

perceptions are reported in the sixth and final section.

Also, in this

section, findings resulted from hypotheses testings are presented.

DESCRIPTION OF RESPONDENTS

The first part of the instrument used for this study consists of a

set of questions designed to obtain some specified personal information

about the respondents.

150 questionnaires were distributed to 50 aided

secondary schools, with one principal, one non-graduate teacher and one

I!T:1I

graduate teacher drawn from each school.

responses was 93 or 62 percent.

The number of returned

One response or 1.1 percent of the total

returns was found to be unusual, and therefore was discarded.

In order

that three respondents can be drawn from each sample school, the other

two responses from the same school were eliminated too.

The total number

of usuable response was 90 or 60 percent of the total number distributed.

Table 4.1 showed male subjects were slightly in the majority.

Distribution by Sex

Table 4.1:

Teachers

SexN

Principals

______ ______ _____

Z

N

Male

32

53.3

18

60

Female

28

46.7

12

40

Total

60

30

100

100

Page 41

The majority of subjects were in theiryouth, between 31-40 years old,

indicated in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2:

Distribution by Age

-

Teachers

Age Group

Principals

________ _____ ______

N

Z

Z

N

20-30

28

46.7

0

0

31-40

29

48.3

6

20

41 - 50

3

5.0

18

60

over50

O

O

6

20

60

100

30

100

Total

Table 4.3 and Table 4.4 indicated the number of years of experience of

teachers and principals.

Table 4.3:

Distribution by Years of Experience in Teaching

Experience in Teaching

N

Z

Years

27

45.0

6 - 10 Years

12

20.0

11 - 15 Years

11

18.3

Over 15 Years

10

16.7

Total

60

1 - 5

100

Page 42

Table 4.4:

Distribution by Years of Experience as an Aided Secondary

School Principal

Experience as An Aided Secondary School Principal

i - s

Z

N

Years

10

33.3

6 - 10 Years

12

40.0

11. - 15 Years

4

13.3

Over 15 Years

4

13.3

Total

30

99.9

Nearly half of the teachers, 45 percent, had between 1-5 years of

teaching experience.

For principals, 40 percent had 6-10 years of

experience as an aided secondary school principal.

The findings revealed among the graduate teachers 22 or 73.3 percent

obtained Cert.Ed. oi

Dip.Ed. from the local universities.

Nearly half of

the teachers, 45.5 percent got the professional qualification between

1981-1987 as shown in Table 4.5.

Page 43

Table 4.5:

Distribution by Year of Obtaining Professional Qualification

Teachers

Year of Obtaining Cert.Ed./Dip.Ed.

N

Before 1970

1

4.5

1971 - 1975

6

27.3

1976 - 1980

5

22.7

1981 - 1987

10

45.5

Total

22

100

In regard to principals,29 or 96.7 percent obtained the professional