Document 299792

Provincial

Hospice

Palliative Care

Volunteer Resource

Manual

Provincial Hospice Palliative

Care Volunteer Resource Manual

Sandi Jantzi, Sandra Murphy, Judy Simpson and The Hospice

Palliative Care Volunteer Project Team

June 2003

© Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, 2003

May be reprinted with permission from Cancer Care Nova Scotia (1-866-599-2263).

Table of Contents

Preamble

Table of Contents

Introduction........................................................................................................................................ i

Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................ iii

How to Use the Resource Manual...................................................................................................... v

Section I

Making the Case for Volunteers ........................................................................................................

Making the Case for Manager of Volunteers.....................................................................................

Universal Declaration on Volunteering .............................................................................................

Universal Declaration on the Profession of Leading and Managing Volunteers ...............................

1

4

7

11

Section II

Volunteer Program Standards, Policies and Practice Introduction ....................................................

Principles ...........................................................................................................................................

Principle I...........................................................................................................................................

Principle II .........................................................................................................................................

Principle III ........................................................................................................................................

Principle IV........................................................................................................................................

Principle V .........................................................................................................................................

Principles and Standards for Volunteers in Palliative Care ...............................................................

Sample Policies..................................................................................................................................

Volunteer Resource Management Definitions...................................................................................

16

19

21

41

53

80

90

117

122

127

Section III

Orientation of Volunteers .................................................................................................................. 130

Section IV

Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Training Program .......................................................................

Module I: Introduction to Hospice Palliative Care ............................................................................

Module II: Communication Skills......................................................................................................

Module III: Psychosocial Elements of Dying ....................................................................................

Module IV: Spiritual Issues ...............................................................................................................

Module V: Pain and Symptom Management .....................................................................................

Module VI: The Process of Dying .....................................................................................................

Module VII: Grief and Bereavement .................................................................................................

Module VIII: Family Centered Care..................................................................................................

Module IX: Caring for Yourself ........................................................................................................

Module X: Legal Issues in Palliative Care.........................................................................................

Module XI: Funeral Planning ............................................................................................................

Palliative Care Definitions .................................................................................................................

Certificate of Participation .................................................................................................................

160

165

202

227

248

277

305

327

360

382

400

402

408

436

Section V

Bibliography and References ............................................................................................................. 438

i

INTRODUCTION

Historically, hospice palliative care programs and services within Nova Scotia have

developed based on available local resources and to meet community needs, which has

led to considerable province-wide diversity. At the June 2001 Palliative Care Roundtable

hosted by Cancer Care Nova Scotia (CCNS) it was identified that volunteers, and the

clients and families they serve, would benefit from some standardization in training and

support. In addition to the lack of a standardized evidence-based core curriculum, it was

noted that there was inconsistency in terms of volunteer management and policies or

guidelines governing the involvement of volunteers throughout the province.

Just as the hospice palliative care community has been working to develop a more

consistent approach to care, we are also working to develop a more consistent approach

to hospice palliative care volunteer development. To that end, in 2002 CCNS and the

Nova Scotia Hospice Palliative Care Association (NSHPCA) entered into a partnership to

support a provincial volunteer development project to ensure that hospice palliative care

volunteers receive training and education and are supported in their efforts. Both

organizations recognize the centrality of volunteers to the delivery of excellent hospice

palliative care.

Sandra Murphy, a consultant with expertise in volunteer development, was hired to work

with CCNS and NSHPCA to facilitate the development of a manual covering issues such

as screening, education, policy development, recruitment and retention.

Over a nine-month period beginning in September 2002 a group of individuals with

hospice palliative care volunteer content expertise, representing the nine District Health

Authorities and the IWK, worked together as a project team. The team utilized past work

and built on the successes of current hospice palliative care volunteer programs

throughout the province and in Canada in order to develop:

• a Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual, which encompasses

all aspects of the volunteer development cycle from recruitment to training and

support as well as evaluation;

• a recognized Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Training Program;

• a dissemination and training strategy for the project.

Team members are very enthusiastic about the potential of this project. They feel that

setting provincial standards will provide basic assistance in the increasingly specialized

area of hospice palliative care volunteerism, and serve as a benchmark against which

programs can be measured. This project will result in the establishment of a provincewide core curriculum for the training of hospice palliative care volunteers as well as a

more consistent approach to volunteer management and policies governing the

involvement of volunteers in Nova Scotia.

A provincial certificate of participation will be issued to all volunteers who participate in

the new Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Training Program after its official

launch at the 14th Annual NSHPCA Conference and Annual General Meeting that was

held in May 2003.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

ii

CCNS and the NSHPCA recognize current and past volunteers who have previously

participated in training that meets the standards for the new provincial program as

volunteers who have equivalent training. The certificate of participation received from

previous training is deemed equivalent to the new provincial certificate of participation.

The project team would like to express their gratitude to the following

organizations/programs for their support and/or use of their resource material:

• British Columbia Hospice Palliative Care Association, “The Caring Community: A

Field Book for Hospice Palliative Care Services” 1999;

• Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, “A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative

Care: Based on National Principals and Norms of Practice” March 2002;

• Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association and Canadian Association for

Community Care, “Training Manual for Support Workers in Palliative Care” 1998;

• Cape Breton Health Care Complex Palliative Care Service;

• Circle of Care, “Palliative Care Visiting Homemaker Training Program” 1992;

• Colchester/East Hants Palliative Care Program;

• Eastern Shore Palliative Care Association;

• Lunenburg and Queens Palliative Care Program;

• Northwoodcare Incorporated;

• Pictou County Health Authority;

• QEII Health Science Centre Palliative Care Program;

• Strait Richmond Hospice Program;

• Victoria Hospice Society, “Palliative Care for Home Support Workers” 1995.

• Victorian Order of Nurses – Annapolis Valley Branch;

• Volunteer Canada, “Volunteer Management Intensive” 1999. (In particular materials

from the program, which came from the Community Service Council, Volunteer

Centre of Newfoundland and Labrador.)

In closing, CCNS and the NSHPCA wish to acknowledge all project team members and

thank them for their dedication to this very important work. The team worked well

together, shared and learned from each other’s experience. Both organizations are

optimistic that their joint efforts will advance volunteer development and management

within the hospice palliative care community in Nova Scotia.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

iii

Acknowledgements

Cancer Care Nova Scotia and the Nova Scotia Hospice Palliative Care Association

would like to thank the numerous individuals and organizations who generously provided

financial support, assistance with content, encouragement and guidance with formatting

and layout of the training program and development of this Hospice Palliative Care

Volunteer Resource Manual. Without their support, this manual would not have been

possible. We have tried to be as inclusive and accurate as possible. Any omission is

purely an error.

Project Partners

Cancer Care Nova Scotia

Judy Simpson, Project Manager

Nova Scotia Hospice Palliative Care Association

Sandi Jantzi, NSHPCA Board Representative

Project Consultant

Sandra Murphy, Researcher, Team Facilitator and Writer

Production Team

Cavell Ferguson, Typing, Layout and Graphic Design

Lisa Houghton, Copy Editor, Printing and Compiling

Organizations/Programs

British Columbia Hospice Palliative Care Association

Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, Ottawa, Ontario

Canadian Association of Community Care, Ottawa, Ontario

Cape Breton Health Care Complex Palliative Care Service

Circle of Care, North York, Ontario

Colchester/East Hants Palliative Care Program

Eastern Shore Palliative Care Association

Lunenburg and Queens Palliative Care Program

Northwoodcare Incorporated

Pictou County Health Authority

QEII Health Science Centre Palliative Care Program

Strait Richmond Hospice Program

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

iv

Victoria Hospice, Victoria, British Columbia

Victorian Order of Nurses – Annapolis Valley Branch

Volunteer Canada, Ottawa, Ontario

Project Team

Rose Anderson - Cape Breton District Health Authority

Sharon Barron - Cape Breton District Health Authority

Nancy Cameron - Guysborough Antigonish Strait Health Authority

Krista Canning - Colchester East Hants Health Authority

Janet Carver - South Shore Health

Lillian Cochrane - Annapolis Valley Health

Louise Coutreau - Annapolis Valley Health

Sheila D’Eon - South West Health

Catherine Doucet - South West Health

Elaine Finlay - South Shore Health

Gerry Helm - Cumberland Health Authority

Debbie Horne - Guysborough Antigonish Strait Health Authority

Dennis MacDonald - Pictou County Health Authority

Carol McKeen - Cape Breton District Health Authority

Linda Mills - Capital Health

Elinor Mullen - South West Health

Karen Newton - Capital Health

Melanie Parsons-Brown - Capital Health

David Sanford - Annapolis Valley Health

Maxine Thibault - Capital Health

Kimberley Widger - IWK Health Centre

Lynn Yetman - Colchester East Hants Health Authority

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

v

HOW TO USE THE

RESOURCE MANUAL

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

vi

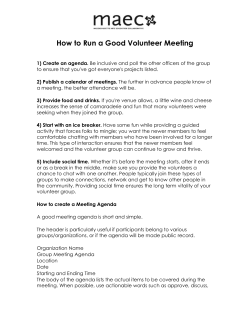

HOW TO USE THE RESOURCE MANUAL

The Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual has been developed

as a tool for use by Hospice Palliative Care Programs across Nova Scotia and more

particularly for the member of the Care Team who has responsibility for managing or

coordinating volunteers.

It is laid out in a manner that will enable the user to access it as a reference tool,

particularly on issues relating to the management of volunteers. It is also structured so

different sections; forms, resource sheets, etc. can be removed and copied and or adapted

for easy use or distribution. Some of the material has been repeated and put in different

formats for the varying usages to which it might be put. For example: The Standards of

Volunteer Management are integrated throughout the section on Principle, Standards,

Policies and Procedures, but there is also a section, which lists them all together for easy

reference.

Because almost every section of the resource manual has a different target audience, the

following is a brief overview of how each section can be used.

Making the Case for Volunteers in Hospice Palliative Care/Making the Case for the

Manager of Volunteer Resources as part of the Hospice Palliative Care Team:

Who should use this section?

This is a tool for the Coordinator of Hospice Palliative Care or the person within the

Hospice Palliative Care Team who involves and supports volunteers to use to make the

argument for the centrality of volunteers in the care of the dying. It also makes the

argument for a paid member of the team designated to work with those volunteers.

How is this section structured?

This section is laid out as a fact and information sheet for easy usage.

Who is the audience?

The audience for this material are the persons in decision-making positions around

program structure, and financial and human resource allocations. It can also be used in

situations where others are questioning the need for or the importance of volunteers to the

system.

How can it be used?

The materials here can be handed out or circulated at staff meetings; sent to CEO’s, board

members, government officials and politicians as an educational tool; or attached to a

budget submission. The Case for Volunteers can also be included in the volunteer

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

vii

manual or given to volunteers at orientation to underline their importance to the Care

Team

Principles, Standards, Policies and Procedures for Volunteers in Hospice Palliative

Care

Who should use this section?

This section is meant almost solely for the use of the person responsible for developing

and managing the volunteer component of the hospice palliative care program.

How is this section structured?

This section moves from general statements of principle to the practical procedures for

the volunteer program. Supporting five overriding principles for volunteers in hospice

palliative care are proposed program standards, with supporting policies and procedures.

Each procedure has a separate two or three page overview of basic information drawn

from standard writings and thinking on volunteer resource management. These are

backed up with a number of easy-to-use resource sheets, which include checklists, forms,

etc.

At the end of the section there is a compilation in list form of the principles and

standards, a compilation of sample policies, and a list of helpful definitions, which

include hospice palliative care volunteer programs from around the province.

Who is the audience?

The information in this section is initially directed at the Manager of Volunteer

Resources but it will be helpful for other team members as well. Ultimately, it should

have an impact of the program volunteers and the people they serve.

How can it be used?

The information can be used in developing a volunteer program that is grounded in firm

principles and standard,s and is set in a strong policy framework. Much of the material is

very practical in nature and will help managers save time by using an existing tool

instead of having to develop their own.

The policy section of the document is not meant to be adopted as is, however, but only as

a guide to policy issues which may need to be addressed in each program.

It is hoped that this section will lead to standardization in hospice palliative care

volunteer programs across Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotia Hospice Palliative Care

Association had previously approved the Standards, which have been used and adapted.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

viii

An Orientation for Volunteers in Hospice Palliative Care

Who should use this section?

This section is meant as a tool for the Manager of Volunteer Resources to use as they

prepare an orientation for their new volunteers.

How is the section structured?

The orientation is laid out in workshop format with ideas for content, helpful exercises

etc. Each manager will need to bring their own program specific information to this

session, but where the information is general to the role of volunteers in hospice

palliative care, materials, resources, exercises and handouts are provided.

Who is the audience?

The information in the orientation is ultimately directed at the volunteer.

How can it be used?

The Manager of Volunteer Resources can use the orientation overview, as it is, to

orientate their volunteers. The material can also be made available to others who may be

involved in the orientation of new volunteers. Orientation is always specific to a

particular setting and program-specific, so material will need to be fully integrated into

the session.

Provincial Training Program for Volunteers in Hospice Palliative Care in Nova

Scotia

Who should use this section?

This section is aimed at the person responsible for planning and organizing the training of

new volunteers in hospice palliative care and the individuals who may be recruited to

present the curriculum material.

How is the information structured?

This section is laid out in nine separate modules - each representing from 1 ½ hours to 3

hours of training - on topics agreed to as being necessary for the volunteer in hospice

palliative care in Nova Scotia. Facilitators offering components will get a general

information sheet for facilitators and presenters, a specific overview sheet for each

module, an outline of the materials for presentation, copies of transparencies and

handouts, and extra resource materials either for their own use or for distribution. Each

module has an evaluation sheet, which can be copied for the use at the end of each

section. In addition, there are extra resources included around each topic, which may or

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

ix

may not be used. The facilitators may use the materials as they are presented or adapt it

to their own training style, as long as the key components of each module are covered.

In addition to the nine modules, two-resource sheets for information sessions on legal

issues and funeral planning are included.

At the end of the modules is a list of definitions, which should be copied for distribution

to the participants. There is also an evaluation form that can be used for follow up

evaluation of the program after the volunteer has served for approximately six months.

Who is the audience?

The material in the Provincial Training Program is directed entirely at people who wish

to become volunteers in hospice palliative care and is therefore aimed at their level.

How can it be used?

This material can be used as is, by Managers of Volunteer Resources and the facilitators,

and the resource people they recruit to help train the volunteers. The topics and the

content have been reviewed and accepted by a project team composed of hospice

palliative care coordinators and managers of volunteer resources in hospice palliative

care from across Nova Scotia. Volunteers who complete the program will be entitled to

receive a provincial certificate of participation.

Many programs may not be at a stage where they can deliver the program fully but

having the curriculum should make it easier to introduce and will also provide a standard

to which all programs can strive.

Other sections

In addition to the sections mentioned, the resource manual will provide extra support

material, including stories, poems, quotes, prayers, jokes etc. which can be used in a

variety of ways. It also provides a list of available print, audio and video resources which

would be helpful in a hospice palliative care volunteer program, and around the

management of volunteers.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

1

MAKING THE CASE FOR VOLUNTEERS

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

2

VOLUNTEERS IN HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE INITIATIVE

Making the Case for Volunteers

We all face the death of people important in our lives [loved ones] and we hope for quality end

of life care for them, and eventually for ourselves. Society, therefore, requires excellent hospice

palliative care services. An essential component of that service is the involvement of ordinary

citizens as volunteers.

“He listened to my frustration and just let me talk.”

“You are wonderful people, you were so good to her and the family. There are no words to

describe the good you do.”

Values statement:

“Volunteering is a fundamental building block of civil society....{it} is the way in which:

human values of community, caring and serving can be sustained and strengthened”

Universal Declaration on Volunteering, International Association for Volunteer Effort,

2001.

The involvement of volunteers in hospice palliative care programs is central to the

philosophy and principles of the hospice palliative care movement. Volunteers are the way

in which the community is involved at the most personal level in the care and support of the

dying.

In many cases volunteers were the first in their communities to recognize the need for

hospice palliative care services, to advocate for it and to develop the resource base and

structure for its implementation. The delivery of many hospice palliative care services

continue to function and thrive because of community based voluntary groups and their

volunteers.

Volunteers are an essential component of the hospice palliative care team. Through their

involvement, they make concrete the desire and the commitment of Nova Scotian society and its

citizens to quality end of life care.

By their involvement hospice palliative care, volunteers:

Provide consistency for clients, families and paid staff

Provide commitment to quality treatment and end of life care

Build relationships with clients and families which support them through difficult times

Enhance flexibility in the system of care

Provide a supplement to existing services

Advocate on behalf of the individual client and service

Undertake tasks which enhance quality of life for clients and their families

Work with the professional team to identify the needs of clients and families.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

3

Bring the community perspective to the service

Enhance resources for service delivery

Provide the invaluable “gift of time”

VOLUNTEERS ARE A VITAL PART OF THE HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE TEAM

Volunteers in hospice palliative care need to be supported and recognized. It is important

that the centrality of volunteers to hospice palliative care be acknowledged by everyone and

every structure that has anything to do with service delivery. These include:

Policy makers

Government departments/federal /provincial

Funders

District Health Authorities

Community Health Boards

Administrators of service providers

Professional staff members and teams

Clients and families

Supporting volunteers in hospice palliative care involves:

Development of an appropriate policy framework

Allocation of sufficient program funds and resources

Designation of a specific Manager of Volunteer Resources

Provision of adequate and standardized training

Recognizing volunteers in hospice palliative care involves:

Reflection of their importance in the organizational chart

Inclusion in a meaningful way on the hospice palliative care team

Acknowledgment publicly of their contribution

Provision of adequate and standardized training

VOLUNTEERS GIVE THE FREE GIFT OF TIME, BUT THEY AREN’T FREE!

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

4

MAKING THE CASE FOR THE

MANAGER OF VOLUNTEER RESOURCES

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

5

VOLUNTEERS IN HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE INITIATIVE

Making the Case for the Manager of Volunteer Resources

To ensure that hospice palliative care volunteer services are of the highest quality, volunteers

must be properly educated and trained, supported, recognized and protected. A designated

Manager of Volunteer Resources is an essential component of the hospice palliative care team.

Values statement:

As the international professional association for volunteer leadership, the Association for

Volunteer Administration envisions a world in which the lives of individuals and communities

are improved by the positive impact of volunteer action.

“This vision can best be achieved when there are people who make it their primary

responsibility to provide leadership in the management of volunteer resources, whether in the

community or within organizations.” Universal Declaration On the Profession of Leading and

Managing Volunteers. Association for Volunteer Administration 2001.

The involvement of volunteers is central to the philosophy and principles of the hospice

palliative care movement. Best practices in volunteer management require that there be a

designated Manager of Volunteer Resources in order that the hospice palliative care volunteer

program be effective and provide quality service to the dying and their loved ones.

In order for the Manager of Volunteer Resources to serve effectively he/she in turn must be

properly trained, supported, recompensed and recognized.

By their involvement in hospice palliative care, Managers of Volunteer Resources:

Develop volunteer programs that work for the benefit of clients, families of clients, and

the hospice palliative care program

Ensure that the appropriate policy framework and procedures are in place to protect the

program clients, the organization and the volunteer

Recruit appropriate volunteers to the program

Ensure the volunteers are properly screened and prepared for work with dying people

and their families

Help build the motivation and commitment of volunteers

Facilitate understanding and cooperation between paid staff and volunteers

Provide adequate supervision, feedback and support for volunteers

Maintain appropriate records

Ensure regular and appropriate recognition for the volunteer

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

6

THE MANAGER OF VOLUNTEER RESOURCES IS A VITAL PART OF

THE HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE TEAM

Managers of Volunteer Resources in hospice palliative care need to be supported and

provided with the resources they need to do their jobs well. They need this support to come

from:

Boards

Senior Management in Organizations

Budget Managers

Funders

Other professionals in the field

The community

Clients of the service

Supporting the Manager of Volunteer Resources for work in Hospice Palliative Care

involves:

Hiring a person specifically trained for the role

Budgeting of adequate program resources

Provision of resources and opportunities for training and development

Recognizing the Manager of Volunteer Resources in Hospice Palliative Care involves:

Ensuring a salary commensurate with the job responsibilities

Positioning appropriately on the organizational chart

Acknowledgment publicly of their importance to the volunteer program

INVESTING IN VOLUNTEER EFFORTS BUILDS PROGRAM CAPACITY

TO PROVIDE QUALITY CARE FOR THE DYING!

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

7

UNIVERSAL DECLARATION ON VOLUNTEERING

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

8

Universal Declaration on Volunteering

Volunteering is a fundamental building block of civil society. It brings to life the noblest

aspirations of humankind ---the pursuit of peace, freedom, opportunity, safety, and justice for

all people. In this era of globalization and continuous change, the world is becoming smaller,

more interdependent, and more complex. Volunteering - either through individual or group

action - is a way in which:

-

Human values of community, caring, and serving can be sustained and strengthened;

Individuals can exercise their rights and responsibilities as members of communities,

while learning and growing throughout their lives, realizing their full human potential;

and,

Connections can be made across differences that push us apart so that we can live

together in healthy, sustainable communities, working together to provide innovative

solutions to our shared challenges and to shape our collective destinies.

At the dawn of the new millennium, volunteering is an essential element of all societies. It

turns into practical, effective action the declaration of the United Nations that "We, the

Peoples" have the power to change the world.

This Declaration supports the right of every woman and child to associate freely and to

volunteer regardless of their cultural and ethnic origin, religion, age, gender, and physical,

social or economic condition. All people in the world should have the right to freely offer

their time, talent, and energy to others and to their communities through individual and

collective action, without expectation of financial reward.

We seek the development of volunteering that:

-

Elicits the involvement of the entire community in identifying and addressing its

problems;

Encourages and enables youth to make leadership through service a continuing part of

their lives;

Provides a voice for those who cannot speak for themselves;

Enables others to participate as volunteers;

Complements but does not substitute for responsible action by other sectors and the

efforts of paid workers;

Enables people to acquire new knowledge and skills and to fully develop their personal

potential, self-reliance and creativity;

Promotes family, community, national and global solidarity.

We believe that volunteers and the organizations and communities that they serve have a

shared responsibility to:

-

Create environments in which volunteers have meaningful work that helps to achieve

agreed upon results;

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

9

-

Define the criteria for volunteer participation, including the conditions under which the

organization and the volunteer may end their commitment, and develop policies to guide

volunteer activity;

Provide appropriate protections against risks for volunteers and those they serve;

Provide volunteers with appropriate training, regular evaluation, and recognition;

Ensure access for all by removing physical, economic, social, and cultural barriers to

their participation.

Taking into account basic human rights as expressed in the United Nations Declaration on

Human Rights, the principles of volunteering and the responsibilities of volunteers and the

organizations in which they are involved, we call on:

All volunteers to proclaim their belief in volunteer action as a creative and mediating force

that:

-

Builds healthy, sustainable communities that respect the dignity of all people;

Empowers people to exercise their rights as human beings and, thus, to improve their

lives;

Helps solve social, cultural, economic and environmental problems; and,

Builds a more humane and just society through worldwide cooperation.

The leaders of:

-

All sectors to join together to create strong, visible, and effective local and national

"volunteer centers' as the primary leadership organizations for volunteering".

Government to ensure the rights of' all people to volunteer, remove ally legal barriers

to participation, to engage volunteers in its work, and to provide resources NGOs to

promote and support the effective mobilization and management of volunteers;

Businesses to encourage and facilitate the involvement of its workers in the community

as volunteers and to commit human and financial resources to develop the infrastructure

needed to support volunteering;

The media to tell the stories of volunteers and to provide information that encourages

and assists people to volunteer;

Education to encourage and assist people of all ages to volunteer, creating

opportunities for them to reflect on and learn from their service;

Religion to affirm volunteering as an appropriate response to the spiritual call to all

people to serve;

Non Government Organizations to create organizational environments that are

friendly to volunteers and to commit the human and financial resources that are required

to effectively engage volunteers.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

10

The United Nations to:

-

Declare this to be the "Decade of Volunteers and Civil Society" in recognition of the

need to strengthen the institutions of free societies; and,

Recognize the "red V" as the universal symbol for volunteering.

International Association for Volunteer Effort challenges volunteers and leaders of all sectors

throughout the world to unite as partners to promote and support effective volunteering,

accessible to all, as a symbol of solidarity among al1 peoples and nations, IAVE invites the

global volunteer community to study, discuss, endorse and bring into being this Universal

Declaration on Volunteering.

Adopted by the international board of directors of IAVE - The International Association for

Volunteer Effort at its 16th World Volunteer Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, January

2001, the International Year of Volunteers.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

11

UNIVERSAL DECLARATION ON THE PROFESSION

OF LEADING AND MANAGING VOLUNTEERS

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

12

Universal Declaration on the Profession of Leading and Managing Volunteers

As the international professional association for volunteer leadership, the Association for

Volunteer Administration envisions a world in which the lives of individuals and communities

are improved by the positive impact of volunteer action.

This vision can best be achieved when there are people who make it their primary responsibility

to provide leadership in the management of volunteer resources, whether in the community or

within organizations.

These "leaders of volunteer resources"* optimize the impact of individual and collective

volunteer action to enhance the common good and enable humanitarian benefit. These leaders

are most effective when they have the respect and support of their communities and/or their

organizations, appropriate resources and the opportunity to continually develop their knowledge

and skills.

With the growth of volunteering worldwide there is recognition that the time and contribution of

volunteers must be respected, and that their work must benefit both volunteers and the causes

and organizations they serve.

Thus, we affirm and support the Universal Declaration on Volunteering adopted by IAVE - The

International Association for Volunteer Effort -, which states "Volunteering is a fundamental

building block of civil society. It brings to life the noblest aspirations of humankind - the pursuit

of peace, freedom, opportunity, safety and justice for all people.... At the dawn of the new

millennium, volunteering is an essential element of all societies." (The complete text is available

at www.iave.org.)

As volunteering has expanded globally, the need has emerged for strong leadership and

management of volunteers. Increasingly, this is recognized as a professional role.

*This phrase applies equally to terms like administrators, managers, coordinators and

directors of volunteers. For this declaration, the term "Director of Volunteers" was selected

to represent these many terms.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

13

Value and Contribution of Directors of Volunteers

Directors of Volunteers promote change, solve problems, and meet human needs by mobilizing

and managing volunteers for the greatest possible impact.

Directors of Volunteers aspire to:

•

Act in accordance with high professional standards.

•

Build commitment to a shared vision and mission.

•

Develop and match volunteer talents, motivations, time availability and differing

contributions with satisfying opportunities.

•

Guide volunteers to success in actions that are meaningful to both the individual and the

cause they serve.

•

Help develop and enhance an organizing framework for volunteering

Role

Directors of Volunteers mobilize and support volunteers to engage in effective action that

addresses specified needs.

As Directors of Volunteers we strive to:

-

Be innovative agents for change and progress.

-

Be passionate advocates for volunteering.

-

Welcome diverse contributions and ideas.

-

Develop trusting and positive work environments in which volunteers and other resources are

effectively engaged and empowered.

-

Ensure the safety and security of volunteers.

-

Develop networks and facilitate partnerships to achieve desired results.

-

Be guided by, and committed to the goals and ideals of the cause/mission towards which we

are working and to continually expand our knowledge and skills.

-

Communicate sensitively and accurately the context, rationale, and purpose of the work we

are doing.

-

Learn from volunteers and others in order to improve the quality of our work.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

14

Core Beliefs

As Directors of Volunteers, we hold these beliefs and seek to demonstrate them in our

actions:

We believe in the potential of people to make a difference.

We believe in volunteering and its value to individuals and society.

We believe that change and progress are possible.

We believe that diversity in views and in voluntary contribution enriches our effort.

We believe that tolerance and trust are fundamental to volunteering.

We believe in the value of individual and collective action.

We believe in the substantial added value represented by the effective planning, resourcing

and management of volunteers.

We also believe that we share the responsibility:

To manage the contributions of volunteers with care and respect.

To act with a sense of fairness and equity.

To ensure our services are responsible and accountable.

To demonstrate the practices of honesty and integrity.

The complexity of the problems the world faces reaffirms the power of volunteering as a way

to mobilize people to address those challenges.

In order for volunteering to have the greatest impact and to be as inclusive as possible, it must be

well planned, adequately resourced and effectively managed. This is the responsibility of

Directors of Volunteers.

They are most effective when their work is recognized and supported. Therefore, we call on

leaders in:

-

Non-governmental and civil society organizations, to make volunteering integral to

achieving their missions and to elevate the role of volunteer directors within the

organization.

Government at all levels, to invest in the sustainable development of high quality volunteer

leadership and to model excellence in the management of volunteers.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

15

-

Business and the private sector, to understand the importance of volunteer management

and to assist volunteer-involving organizations in developing this capacity

Funders and donors, to support the commitment of resources to build the capacity of

volunteer management.

Education, to provide opportunities for leaders of volunteers to continually expand

their knowledge and skills.

We call upon Directors of Volunteers worldwide to accept this Declaration, to integrate and

embody it in our shared work, and to promote and encourage its adoption.

While we recognize that all countries in the world do not approach volunteer development in the

same way, this Declaration is intended to encourage all those concerned with the advancement of

this profession, to aspire to these statements.

Developed by the International Working Group on the Profession

Convened by the Association for Volunteer Administration Toronto,

Ontario Canada 2001

With representation from:

Argentina, Bangladesh, Canada, England, Hungary, Israel, Maurtius, Mexico,

Nepal, New Zealand, Scotland, United States

Association for Volunteer Administration

AVA

P.O. Box 32092 Richmond, VA 23294 USA Phone: 804-346-2266 Fax: 804-346-3318

E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.avaintl.org

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

16

VOLUNTEER PROGRAM

PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, POLICIES

AND PRACTICE

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

17

VOLUNTEER PROGRAM

PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, POLICIES, AND PRACTICE

Introduction:

This section of the resource kit is meant as a tool for Managers of Volunteers in Nova Scotia to

develop an effective hospice palliative care volunteer program. It draws on the work that was

done in developing standards of practice by the Nova Scotia Hospice Palliative Care Association.

These were previously endorsed by the Association’s members, reviewed and endorsed again

with some suggestions for revisions by the project team for the Volunteers in Palliative Care

Initiative.

The section also draws on the excellent work done by the British Columbia Hospice and

Palliative Care Association (BCHPCA) around Standards development for volunteer programs in

hospice palliative care and documented in its book The Caring Community: A Field book of

Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Services, 1997. This work grows out of the CHPCA

Standards and is the basis for current work being done on a national level around standards for

hospice palliative care volunteer programs.

In line with the rest of this Resource Kit, the emphasis is not so much on reinventing the wheel

but on organizing the material for the use of hospice palliative care volunteer programs in Nova

Scotia in a manner that will make it user friendly, practical and will assist with its acceptance and

utilization in the diverse programs across the province. This in turn, will lead to a

standardization of practice while still allowing for flexibility to reflect local realities and needs.

How to Use This Section:

The section will start with a sheet of general principles (taken from the BCHPCA’s Caring

Community field book) then standards which grow out of the principles will be outlined starting

with more general standards and policies around volunteer program management and moving to

more specific standards and policies around practice. Each section will be laid out as follows,

although not all standards will require each element.

Statement of Principle and Standard

Policy Implications from the Principle

- The Principles are presented as framework policies for the hospice palliative care

volunteer program.

Sample Policy(s) which relates to the Standard

- These will be samples only and should not be adopted by local programs without

involving all interested parties and making them reflect your own reality. They

will, however, serve to show where you may need to develop policy.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

18

-

Actions, which should flow out of the standard.

A brief general overview sheet on practice that flows out of the standard and

policy.

Resource sheets of forms check lists, etc. related to practice.

A separate listing for quick reference of the principles, standards, and sample

policies.

Definitions.

This section should give the person who is managing volunteers in hospice palliative care in

Nova Scotia a very quick reference tool for use in developing and maintaining an effective

volunteer program which is rooted in national and provincial standards, firmly grounded in a

policy framework, and includes the basics of sound practice. It will by no means be

comprehensive, but direction will be given for users to seek out other sources of assistance.

It should be noted that everyone who is working as a Manager of Volunteer Resources in

Hospice Palliative Care in Nova Scotia should have completed at minimum a basic training

program in volunteer resource management.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

19

PRINCIPLES

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

20

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE

VOLUNTEER SERVICE IN NOVA SCOTIA

PRINCIPLE I: Volunteer Services are an essential component of the hospice palliative

care programs in Nova Scotia.

PRINCIPLE II: Volunteer services are an essential component of the hospice palliative

care interdisciplinary team, providing unique resources for patient, family and team

members, and representing one form of the community’s response to the program.

PRINCIPLE III: The hospice palliative care organization provides resources for

volunteer support.

PRINCIPLE IV: Volunteers who are directly involved in patient/family hospice

palliative care complete a comprehensive and standardized training program.

PRINCIPLE V: The volunteer program operates in a framework of quality assurance

and quality improvement.

The principles are derived from the general principles of hospice palliative care and are adapted

from the Victoria Hospice Association’s Caring Community field book’ Principles for Volunteer

Service in Palliative Care.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

21

PRINCIPLE I

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

22

PRINCIPLE I:

VOLUNTEER SERVICES ARE AN ESSENTIAL COMPONENT OF THE

HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE PROGRAMS IN NOVA SCOTIA.

STANDARD 1: The hospice palliative care volunteer program is reflected clearly in the

organization’s budget.

STANDARD 2: The hospice palliative care volunteer program is positioned appropriately in

the organizational chart.

STANDARD 3: The hospice palliative care volunteer program is adequately supported with

paid staff and a specifically designated Manager of Volunteer Resources.

STANDARD 4: The hospice palliative care volunteer program is carefully planned and

developed within the context of the organization’s own plan and to externally recognized

standards of management of volunteers.

Please note:

Standards 1, 2 and 3 are developed by and directed primarily at the board and senior

management of the organization. They are framework policies.

Standard 4 was developed by board and senior staff and the Manager of Volunteer

Resources. This is an operation policy.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

23

POLICY

PRINCIPLE I:

VOLUNTEER SERVICES ARE AN ESSENTIAL COMPONENT OF THE

HOSPICE PALLIATIVE CARE PROGRAMS IN NOVA SCOTIA.

Policy implication: If this principle was adopted by concerned provincial organizations,

district health authorities and the boards of organizations, which deliver hospice palliative care

services, it is in effect a policy that encapsulates “the principles, values and beliefs of the

organization.” Graff 1999.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

24

STANDARD 1:

The hospice palliative care volunteer program is reflected clearly in the

delivery organization’s budget.

Sample policy statement: The

insert name of program shows its commitment to the hospice

palliative care volunteer program by budgeting appropriate financial resources.

ACTION: The board and senior management of the delivery agency has budgeted adequately

for the volunteer program and this is reflected in the budget in a manner that is consistent with

other program budgets within the organization.

ACTION: The Coordinator of the Hospice Palliative Care Program should be able to break out

the costs for the volunteer component of the program to reflect the true cost of operations.

Included in these calculations should be:

Personnel Costs: Including salary of the Manager of Volunteer Resources, and portion of

other staff salaries dedicated to the volunteer program, including that of the coordinator.

Operating Costs: Including space, equipment, supplies, out of pocket expenses, training

costs, insurance, recognition costs.

ACTION: The Coordinator of the Hospice Palliative Care Program and/or the Manager of

Volunteer Resources should be able to state in monetary terms, to board, senior management and

funders, the value of the time given to the palliative care delivery system by volunteers. (Please

note that this is only one of the means of showing the value of the volunteer program and should

never be used as the main justification.)

STANDARD 2:

The hospice palliative care volunteer is positioned appropriately in the

organizational chart.

Sample policy statement: None needed.

ACTION: The board and senior management have reviewed all organizational charts, and if

the volunteer component is not included or is not adequately positioned in the chart, ensures that

changes are made.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

25

STANDARD 3:

The hospice palliative care volunteer program is adequately supported with

paid staff and a specifically designated Manager of Volunteer Resources.

Sample policy statement: The

insert name of program underlines its commitment to excellence

and clients and program standards by ensuring that a designated Manager of Volunteer

Resources is part of the hospice palliative care team.

ACTION: The board and senior management of the organization is educated about the

importance of the role of Manager of Volunteer Resources and the unique and demanding set of

criteria for this position. They commit themselves to the need for this role in their program and

seek resources to fund it on a permanent basis. Introducing them to the Canadian Code for

Volunteer Involvement would be a means of education.

See the Advocacy Section of the Resource Kit “Making the Case for the Manager of

Volunteer Resources”

STANDARD 4:

The hospice palliative care volunteer program is carefully planned and

developed within the context of the organization’s own plan and to externally

recognized standards of management of volunteers.

Sample policy statement: In line with its commitment to providing quality hospice palliative

care service the insert name of program ensures that the volunteer component is properly planned.

ACTION: See the following Planning Overview and resources, the Policy Development for

Volunteer Programs Overview and resources and Job Design Overview and resources, which

follow.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

26

PRACTICE

Planning

IA Planning a Volunteer Program

Resource Sheets

1. The Planning Process

2. Planning Checklist

Formatted: Bullets and

Numbering

IB Policy Development For Volunteer Programs

Resource Sheets

3. Policy Development for Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Programs

Formatted: Bullets and

Numbering

IC Position Design and Description

Resource Sheets

4. Sample Position Description

5. Position Description

6. Volunteer Position Description

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

Formatted: Bullets and

Numbering

June 2003

27

OVERVIEW SHEET IA

Planning

Planning a Volunteer Program

The need for volunteer programs to be carefully planned cannot be over emphasized. This focus

on planning is particularly important to programs such as hospice palliative care where

volunteers are being called on to play a very important role with a clients group, which is

particularly vulnerable. It is only through careful planning that a volunteer program can be well

integrated into the hospice palliative care team structure and the quality of program delivery can

be assured and assessed.

Careful planning helps to ensure the following:

That the program will be consistent with the mission, goals and objectives of the

organization.

That the program is fully accepted by professional paid staff and clients and their families.

That clearly defined outcomes are in place against which the program can be monitored and

assessed.

That the program is set in the appropriate policy framework.

That the program has the resources it needs to be effective.

That the program will be realistic about what is possible within its resource limitations.

That appropriate risk management structures are in place to protect the clients and their

families, the delivery organization and the volunteers themselves. (Screening issues.)

When should planning occur?:

Planning should take place when a new volunteer program is being considered or developed by

the hospice palliative care program. Planning should also take place if the organization is trying

to regularize, formalize, change or restructure an existing program. Planning should be an

ongoing process informed by program evaluation.

Planning should be undertaken by:

Involving the people who will be affected by the volunteer program is the best possible way to

ensure its full acceptance in the organization. The responsibility for the final plan will probably

lie with the Coordinator of the Hospice Palliative Care Program and/or the Manager of Volunteer

Resources. If it is a new program, a small committee could be formed to oversee the planning.

Approval of the plan may lie at a higher level in the organization.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

28

The elements of the planning process are:

Assessment

Resource preparation

Program objectives and operational plan development

Program implementation

Program monitoring

Outcome assessment

(See Resource Sheet 1 for a complete overview of the planning cycle.)

Key issues for the planning process:

During planning, whether it is for a new hospice palliative care program, or an existing one, the

development of the policy framework and the design of volunteer positions are crucial in terms of

risk management and screening issues. Therefore, this section on planning has separate resource

sheets and materials devoted to these.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

29

RESOURCE SHEET 1

The Planning Process

Assessment:

To ensure that the proposed hospice palliative care volunteer program is consistent with the

overall mission and goals of the program and delivery organization.

To find out if the organization, paid staff and clients will benefit from the program and will

welcome and support it if it is introduced or restructured.

To identify the existing assets/resources that can be built on and if they are sufficient to ensure

the success of the program.

Revisit organizational and program goals and proposed outcomes

Describe target population and programs to be provided

Determine if proposed/revised program will fill a gap (clients)

Assets review

Describe the support available from powers that be

Describe other available assets - time, money, space, existing volunteers, etc.

Determine assets limitations

Resource preparation:

This is the stage at which the person(s) who needs to be involved (the champion for the program)

and get others involved.

Select who is to be primarily involved in the program (and how) e.g. – staff person, staff

committee, or volunteer committee

Train any staff/volunteers who will be involved in the program, on management of

volunteers within the hospice palliative care context

Orientate hospice palliative care team members on the proposed program

Allocate program resources and facilities

Program goals, outcomes and operational plan development:

Describe what the program hopes to achieve in terms of outcomes and how these will be

accomplished.

Establish expected program outcomes (include time lines, indicators of success)

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

30

Determine program activities and sequences

Develop policy framework for the program

Determine volunteer roles

Determine paid staff activities vis-à-vis the volunteer program

Develop volunteer positions and write job descriptions

Develop program monitoring and evaluation system

Develop volunteer manual

Develop localized structure for delivery of the Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer

Training Program

Program implementation:

Recruit volunteers

Interview and do intake screening on volunteers

Orientate and train volunteers

Place/match volunteers

Recognize volunteers

Program monitoring:

Supervise and support volunteers

Evaluate and give feed-back to volunteers

Identify need for additional resources/training, etc.

Take corrective action

Maintain program records

Prepare report on the program

Outcome assessment:

Assess the extent that proposed outcomes were achieved

Assess the effectiveness of the program in meeting its goals

Assess the impact of the program on the clients of hospice palliative care program

Assess the impact on the volunteers

Final report

Process starts again….

Adapted from Making the Most of Volunteer Resources training program of the Community

Services Council Volunteer Centre, St. John’s NL and as used in the Volunteer Management

Intensive Program of Volunteer Canada.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

31

RESOURCE SHEET 2

Planning Checklist

Ask yourself the following when planning your program. You may decide some are not relevant

in your situation, but at least make that decision intentional rather than an oversight!

Have we considered.........?

Yes

No

Support from the powers that be

How many volunteers we'll need

When we'll need them to volunteer

Coordinator - who?

Risk management issues

Written policies

Policy on volunteer involvement

Position descriptions

Budget

Recruitment strategy

Interview and placement procedure

System for checking references, etc.

Written volunteer/agency agreement or letter of understanding

Monitoring and evaluation system

Orientation session

Orientation manual

Who will do the training

Probationary period for volunteers

Evaluation meetings

System for tracking volunteer hours

Reimbursement of volunteer expenses

Necessary space

Necessary supplies

Storage of information

Formal volunteer exit interview

Annual volunteer recognition event

What information is needed to evaluate the program

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

______

It looks daunting, doesn't it? But resist the impulse to quickly initiate a volunteer program operate on the principle "Do it right the first time - it's easier than having to do it over again".

And remember, there is something in this toolkit to help you with all of the above.

From – Volunteers, A Growing Need, Community Access Program Manual

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

32

OVERVIEW SHEET IB

Planning

Policy Development for Volunteer Programs

The importance of having a policy framework at every level to support and define the work of

organizations has never been more important than it is today. Policy defines what is important in

an organization on a philosophical and values basis, reinforces important and acceptable

behavior and proscribes unaccepted and prohibited actions in an organization. Organizations,

and programs within organizations, which are not supported by policy are like a rudderless ship,

which will eventually be driven by sea and wind to founder on the rocks.

The values around delivery of hospice palliative care services by volunteers and the vulnerability

of the clients of the service makes it imperative that this program be supported by carefully

developed policies. The Manager of Volunteer Resources will play an important role in

advocating for appropriate policy for the hospice palliative care volunteer program and in its

development.

Some of the reasons for policy:

To clarify values and beliefs both internally and externally

To ensure continuity for the program

To ensure fairness and equity

To communicate expectations

To support consistency in service delivery

To specify standards

To state rules

Policies can be directed externally so that those outside the organization understand that quality

and excellence are important to the hospice palliative care volunteer program. Sound policies

directed externally can help garner community support for the program. They will make the idea

of being involved with your program more attractive to potential volunteers, community partners

and funders.

Policies directed internally will serve as educational tools for volunteers in learning the values

and beliefs in which their actions and service as volunteers should be grounded. They will serve

as a clear framework against which they can make decisions around their actions in the program

and clarify what they can and cannot do. Policies will provide assurance that the program is well

run and that they are supported in what they are doing.

A strong policy framework is the basis of your program’s risk management efforts.

A strong policy framework supports quality volunteer programs.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

33

What is policy?

A principle in which a position is taken

A plan of action which states specific steps and procedures

Something that applies to everyone in the organization/program

A rule that states a boundary

A rule that implies consequences if broken

Policy can be implicit because of tradition and long-term approaches in an organization, but in

this day and age it is important for volunteer programs to have written policies.

“The matter of policy development for volunteer services has become urgent. The formula is

quite simple: the greater the degree of responsibility of volunteer work itself, the greater the need

for guidelines to ensure safety; the greater the need for policies.” Graff, Management of

Volunteer Services in Canada, 1999.

This section draws heavily on the work of Linda Graff.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

34

RESOURCE SHEET 3

Policy Development for Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Programs

How to write policy:

Be concise: Keep the policy as short as possible without compromising meaning.

Be clear: Make certain that what is meant is stated and that it is understood by the audience

for which it is intended. Use clear language and scrap the jargon.

Be directive: Tell people clearly what is expected. Don’t equivocate. The most important

policies should be the most strongly worded.

Be polite: Even when wording policies, firmly remember you audience is volunteers not

criminals. Don’t word them as if you expect the volunteers to want to ignore them.

Be positive: Design policies, whenever possible, to be motivational and inspiring. Emphasize

the scope for action within the policy rather than what lies outside the policy boundaries.

Be creative: Use pictures, diagrams, graphs and other tools to make your policy manual

attractive and to reinforce the material for the volunteer.

Adapted from: “ Policies for Volunteer Services” from Management of Volunteer Services in

Canada, 1999 and By Definition 1993, both by Linda Graff.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

35

OVERVIEW SHEET IC

Planning

Position Design and Descriptions

One of the essential elements of risk management for any volunteer program is to design

volunteer positions with the view to eliminating, reducing or controlling risk. In hospice

palliative care the volunteer is involved in direct contact, often in unsupervised settings, with

clients and their family members who are extremely vulnerable because of their circumstances.

Increasingly, position design is seen as a powerful tool for volunteer motivation and retention.

This happens when positions have the right elements of challenge, achievement, responsibility

and internal reinforcement or recognition.

Position design is not the same as developing position or job descriptions. Position design is an

exercise that the Manager of Volunteer Resources and others involved in the planning of the

volunteer program must undertake to help guarantee the integration of the volunteer work into

that of the rest of the hospice palliative care team. Lines of responsibility and reporting are made

realistic and workable, the identification of potential risks is done with a view to appropriate risk

management, and that the position is tailored to reinforce volunteer motivation.

The position description grows out of the process of position design and will define for the

volunteer and for those he/she works for and with activities, expectations around the position,

level of responsibility, reporting structures, etc.

Position design is:

-

A pre-requisite for successful integration of the volunteer

A risk management tool

Means of reinforcing motivation and assuring retention

A position description includes:

-

Position title

Purpose/function/rationale

Specific duties in terms of expected results - qualifications/skills/interests

Time commitments

Training/orientation requirements - lines of responsibility

Authority for decision making - location of the activities

Special conditions/parameters/risk management directives

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

36

A position description is a tool that helps determine:

-

Who and where to recruit

Screening concerns around intake

What training is necessary

What level of supervision is needed

What will be addressed in the performance review

What should be recognized

A position description is a tool for use by:

-

The manager of volunteer resources

The volunteer

Staff who interact with the volunteer

Clients of the service

A position description can also be used as a contract between the agency and the volunteer. This is

increasingly recognized as a part of appropriate management of volunteers. It should be recognized

that not all programs are comfortable with this.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

37

RESOURCE SHEET 4

Sample Position Description

Title: Patient and Family Support Volunteer

Purpose: To be with patients who are terminally ill and their families to provide an atmosphere

of caring and support.

Duties:

Listen to or converse with patient or family. Sometimes just to be with the patient in

silence.

Read to the patient, write letters, sing for or with the patient, listen to music, arrange for

videos or games.

Take patients for walks, or to another floor (beauty salon, smoking room, lounge).

Do errands for patients, accompany discharged patients, or go with them to other

departments.

Assist staff with special requests.

Assist with organizing special events---birthdays, anniversaries, and bereavement teas.

Take care of "coffee corner" for patients.

Perform small services for patients, hair care, manicure, hand massage, foot massage, back

massage.

Be with patient at time of death if family is not available.

Time commitment: Four hours a week for one year.

Qualifications: Mature, stable personality, good listening skills, dependable, sense of humour,

able to work as a team member with family and staff.

Training and Skills Development: Must attend the standardized provincial hospice palliative

care volunteer training program in Nova Scotia, and additional in-service as recommenced by the

Manager of Volunteer Resources.

Lines of responsibility: To the Manager of Volunteer Resources and the palliative care team.

Authority for decision-making: The volunteer can make decisions within the framework of the

duties outlined above. Any other requests for service, advise or support from patients, family

members or other staff should be taken to the Manager of Volunteer Resources. If the volunteer

has any doubts about any duty this should also be discussed.

Location: The volunteer will generally work within the confines of the hospice palliative care

unit of the Insert name of program. The patient should only be taken off the unit at the request of the

appropriate staff person. Any planned excursions outside the hospital will be discussed and

arranged in advance with the Manager of Volunteer Resources.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

38

Parameters: The volunteer will maintain confidentiality around their work with patients,

families and within the hospice palliative care unit. The volunteer will follow other guidelines

around the position as provided.

Other: Meal passes will be provided for the volunteer if they are in the hospital over a

mealtime. Parking passes are provided for the volunteer.

Position approval:

Date:

Volunteer's signature:

Manager of Volunteer Resources signature:

Further guidelines attached

Refer to Volunteer Manual for further information

Adapted and compiled from: BCHPCA, Caring Community, 1997; and: Volunteer Canada, A

Matter of Design, 2001.

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

39

RESOURCE SHEET 5

Position Description

Title:

Purpose:

Duties:

Parameters around position:

Skills/Qualities required:

Lines of responsibility:

Time required:

Other requirements (references, training, etc.):

Other (location, benefits, conditions, etc.):

N.S. Provincial Hospice Palliative Care Volunteer Resource Manual

June 2003

40

RESOURCE SHEET 6

Volunteer Position Description

Title/Position:

Goal of position:

Sample activities:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Timeframe:

Length of commitment:

Estimated total hours:

Scheduling:

At discretion of volunteer

Needed ___________________________________________________________________

Worksite:

Qualifications sought:

1.