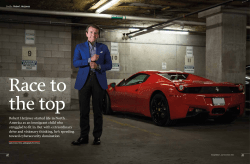

R Reading Strategies