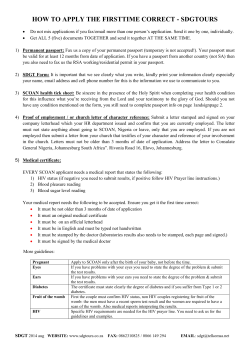

HIV/AIDS LEGAL ASSESSMENT TOOL www.abarol.org ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY MANUAL