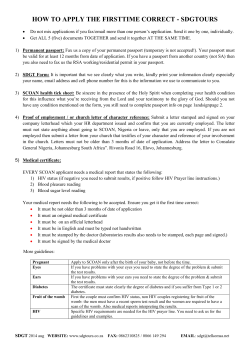

Supporting the HIV Response: A Manual for Civil Society Organizations Injecting Drug Users