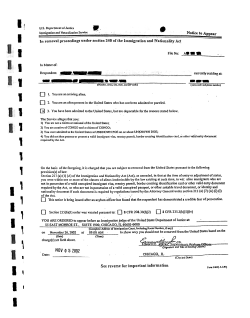

MANUAL FOR CONDUCTING ADMINISTRATIVE