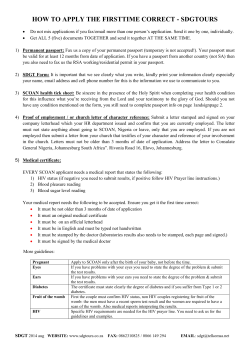

STRUGGLE FOR MATERNAL HEALTH BARRIERS TO ANTENATAL CARE