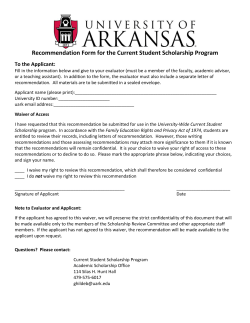

Document 32309