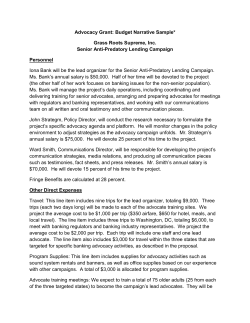

Neutral Citation Number: [2014] EWCA Civ 0417