Essay Structure Review: A Personal Writing Workshop ENG 131 By Sue Stindt

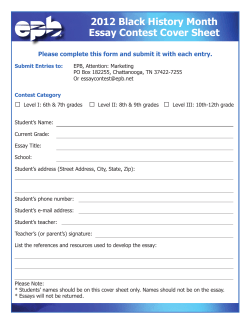

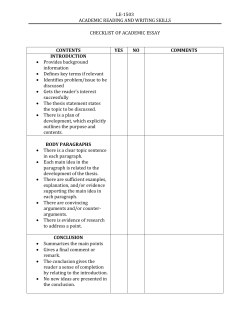

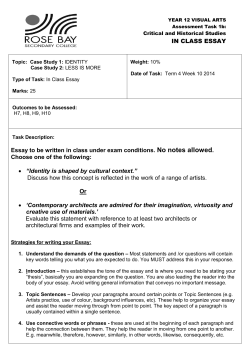

Essay Structure Review: A Personal Writing Workshop ENG 131 By Sue Stindt How to complete this workshop… Thank you for participating in “Essay Structure Review.” This workshop is intended to help you develop and improve organization and structure in your personal (and informative) essays and to apply those skills to academic writing across the curriculum. This workshop is a tutorial and requires your participation. To receive full credit for this two-hour workshop: •Scroll through the slides one by one •Read the information thoroughly, giving each point thought and consideration. Unlike other workshops, the workshop activity, here, comes at the end. The information on the discussion slides is crucial to successfully completing the assignment and will be used as evaluation criteria. At the very end is a final reflection for you to complete. •Complete all of the activity and the reflection. You do not have to complete this workshop in one sitting. You can work through it at your own pace as time allows. •Turn your work in to your instructor for credit when finished In the world around us, most manmade structures and objects have a purpose or a function. If we analyze the structures, we realize that the design and parts support the purpose. Structure and Function (or Purpose) Questions for Thought and Analysis What is the purpose of a windmill? What are the parts of a windmill? How do these parts support its purpose? Structure and Function (or Purpose) What is the purpose of a lighthouse? What are the parts of a lighthouse? How do these parts support its purpose? Essays need structure, too… Any coherent, meaningful piece of writing must have a clear purpose and solid organization and structure. The Structure or Parts of the Essay Support its Purpose… An essay writer must have a reason or purpose for telling a personal story or writing about an experience or character. A writer must make meaning of his or her life experience. Meaning is sometimes revealed as, or even after, the writer writes about a life experience. Using this strategy, the writer may jump right into the story, without a formal introduction. But, the writer must then focus on clearly weaving the theme or meaning into the essay, reinforcing it in the revision process. PURPOSE An essay must convey meaning or purpose by organizing the details of the essay around a theme, a universal experience, or an abstract idea. The theme is the “relevant” idea… what the story, event, or character mean to the writer and what readers can learn from the essay. The theme should be woven throughout the story or essay; it should be evident in each section of its structure– beginning, middle and end. The theme or meaning should emphasize the author’s view or interpretation of a lesson learned, an insight, an understanding, or an abstract idea connected to the event, experience or relationship of the character to the writer. Theme, Meaning or Purpose… A personal essay must have a theme or meaning, a purpose for sharing the story or personal experience. To convey meaning, a writer must… •Discuss an abstract idea (the beauty of love, the harshness of learning justice, the rewards of hard work, the disillusionment of love, the satisfaction of justice, coping with failure despite hard work) that is essential to (that “fits”) his or her story •Convey a lesson learned (I now know that…What this experience made me realize is…This experience gave me an understanding of…) •Share his or her perspective of a universal experience (peer pressure, first kiss, coping with stress, the loss of a loved one, learning the hard way) See the workshop “Writing with Meaning” for many more techniques and ideas for developing meaning. FORM & STRUCTURE The process of constructing an essay includes defining the purpose for a piece (the central idea), crafting a structure for it, and creating the connections. An essay is made of three main sections and smaller parts. The form or design and structure of sections, paragraphs, sentences, and words support the essay’s meaning or purpose. An essay has three large sections--the introduction (beginning), body (middle), and conclusion (end)-made of smaller parts--paragraphs, sentences, transitions, and details, for example. This is true of any academic essay, personal or expository, for English class or any other class. After choosing the story (plot) an essay writer must… Introduce the meaning, purpose or theme in the introduction Weave the theme or idea throughout the body of the essay. All the sub-stories and details contained in the story must support the main or “revelant idea.” A story generally builds to a peak or climax near the end of the body. Re-focus, re-assess, expand on, or discuss the theme or idea in the conclusion Photo: http://www.chihuly.com/installations/early/weaving01.html Let’s take a closer look at the STRUCTURE of an essay by examining the parts… • • • • Introduction Body Conclusion Transition Sentences The Introduction… The introduction is often called “the lead.” A good lead must have a “hook” or a “grabber” – a strong statement that “grabs” the readers’ attention or “pulls readers in.” Most importantly, an introductory paragraph must define the essay’s meaning or theme. The purpose of the essay must be clear. A lead may be one single paragraph or may extend to several paragraphs. Source: http://web.anglia.ac.uk/stu_services/essex/learningsupport/OL-EssayWrting1.htm The Introduction… A solid introduction will: •Arouse the reader’s interest •Set the scene--provide background or context •Reveal tension or conflict •Interpret an experience (briefly) •Identify the theme or idea that the writer will explore The Body… The body consists of the bulk of the story, the paragraphs that tell the story and develop the theme through examples and detailed experiences that build upon each other. The details a writer includes are often called the “supporting details,” details that support the theme or main idea, details that are relevant to the story. The final body paragraph should contain the most poignant information, reaching a peak or a climax. The Conclusion… A conclusion widens the lens and wraps up the essay (draws everything together) without summarizing or repeating what has already been written. A conclusion resolves the tension or conflict. A conclusion discusses, re-frames (puts in perspective) or reflects on the universal theme, idea or life lesson. A conclusion lets the reader know what the writer knows “now” that he/she didn’t know “then” (before the experience). Transition Sentences… A writer must create connections between paragraphs. As you already know, the first sentence of a paragraph is the “topic sentence,” which guides the content of the entire paragraph. The last sentence of each paragraph is just as important. It is a transition sentence and must “urge readers on” to the following paragraph. Transition Sentences… The last sentence of each section of the essay— the introduction, body and conclusion– has a special role: •The last or near last sentence of the introduction should reveal the theme. •The last or near last sentence of the body should be the climax or peak of your story. •The last or near last sentence of the conclusion should reflect on the meaning. A Final Pointer… The ideal essay expands beyond the writer to show readers how they might apply what the author learned or to show readers how they might connect to the writer’s experiences by acknowledging similar experiences. I like to tell students, “This essay is bigger than you.” And ask them, “What can others learn from your experience? How can readers identify with your piece? I urge students to, “Connect to your readers (show and tell) through your essays.” If a writer does the above smoothly and subtly, then he or she will have a terrific essay. Sample Essay Read the essay that follows. Read critically, as described in Chapter 2 of your textbook. Focus your attention on the structure, the content of each section, the transition sentences, and most of all, the meaning. A Sample Essay… Source of Sample Essay: http://students.berkeley.edu/apa/personalstatement/sampleessay.html The Introduction Just six days into army basic training, three hundred and fifty unsuspecting soldier trainees are headed for the gas chamber after lunch. I didn’t eat. I am better off having an empty stomach anyway. It wouldn’t be the first time this week that I would revisit the previous meal during some so called training exercise. I believe the term training exercise means “see if you can make them puke” in drill sergeant language. Just yesterday, my battle buddy, that’s what you call the person you share your bunk with, had to drink two full canteens of water then log roll down a fifty foot hill outside our barracks as a training exercise. She threw up and I’m not sure what type of training she got out of that experience. We are definitely learning quickly that we are not in charge. The gas chamber is just another training exercise. The proper care and usage of a gas mask is very important if you ever find yourself in an area less friendly than Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. Unfortunately, we are learning the important stuff after we learn hose important gas masks are—the hard way. (theme; relevant idea) First Body Paragraph Topic/Transition Sentence Outside the gas chamber, we are all standing in one single file line that extends three hundred and fifty people long from a door that holds my destiny. Development of ideas related to the topic sentence This soldier worm-wiggled with a type of nervousness many of us have never experienced before. They won’t let me die. I figure if I keep repeating these words to myself the trembling fear surging through my body in tempo with my heartbeat would being to subside, but it doesn’t. In groups of four, the drill sergeant sends us to our fate. I’ve had nightmares of dying in combat but none of them ever involved friendly fire of this kind. They won’t let me die, I think again, and again. I begin to shiver, not because I am cold, but because I can no longer register any more comprehendible fears. I can’t run away, some poor schmuck had tried that three days ago and was caught and thrown in jail. I can’t pretend I am sick, that hasn’t worked for anyone so far. I have to do it. Eventually one has to face her fears. My time is today, in approximately eight minutes. End Sentence I will become a new person, alive or dead. Second Body Paragraph Topic/Transition Sentence The soldier-worm wriggles toward the destiny door sooner than I would like, but I am filled with new confidence. Development of ideas related to the topic sentence: (Signpost question addressed-- evidence of responsibility) Two-hundred soldiers have gone before me, now it is my turn. Bring it on. I approach the door and begin to cough. We are instructed to put on our gas masks and enter. I seal the mask around my sweating face and take one last deep, long breath and enter the small building. With my eyes closed, I take three steps forward and bump into the person in front of me. I open my eyes quickly while still holding my breath. The room is very small and perfectly square with only what looks like a drain on the floor in front of us. It is spewing a fog that has filled the room. There is an observation window that spans across one corner of the room.. End sentence What a cruel way to spend your days, watching poor trainees gag in a fog of fears. Continuing Body Paragraphs Topic/Transition sentence A voice comes from the control window instructing us to unmask. Development of ideas related to the topic sentence: (Signpost question addressed-- accomplishment) The time has come. I obey the command given by the voice from above and take one last quick breath and lose the safety of my gas mask. At first I don’t notice a thing. Then it hits me, the feeling of drowning in midair. I can breathe in, but nothing is leaving my lungs. A feeling of fullness burns like wildfire in my chest. Each breath gets shorter and shorter, quicker and more painful. All four of us in the gagging haze have to say our name, rank and serial number. Producing words is unthinkable, but I get to go first. “Private First Class Sara Luciani, 366924321, sir.” The words sputter from my lips. I can’t hear anything else. Three more names follow mine, but I can only concentrate on the feeling of the world getting smaller around me. I’m getting dizzy from the lack of oxygen. My nose is running like a faucet. My skin is burning almost as painfully as my lungs now. I can’t see anything around me. I think I’m going blind. I want to scream, but I can’t breathe. Oh God, please don’t let me die. He can’t hear me either. The others finally cough the words we need to hear and out the door we go on the opposite side of the room from the entry. I can’t see anything because my eyes are burning from the crystals that float in the gas. When I rub my eyes it feels like grinding glass shards into my retinas. My nose is still running profusely, my skin still burns, my lungs are still paralyzed. They won’t let me die, I tell myself as I flap my arms like a bird to force the air back into my lungs . End sentence After a few minutes in the fresh air I slowly retain my eyesight and air returns to my lungs, but my skin will itch and burn for a few more hours. Conclusion Widen the lens beyond the topic at hand and tie up the essay They didn’t let me die, not that day or any of the days in the remaining thirteen weeks of training I endured at that dreadful place. That afternoon we learned the proper way to care for, assemble, wear and store an army issued gas mask. I would go on to learn hand to hand combat, marksmanship with a variety of firearms, bayonet fighting, drill and ceremony, and the proper way to fold my socks, all the skills I needed to be a good soldier. But I also learned courage, honesty, and integrity. Mostly, I learned to be brave. What doesn’t kill you really does make you stronger. Before the gas chamber I didn’t think you could teach people things like bravery and courage. Now I know you can. I spent the following six years as an active duty soldier. I was promoted five times, stationed in three countries, five states, and went through two more advanced training schools. After becoming a veteran of two foreign wars as a combat field medic, I still remember exactly where I was on August 4, 1997. Activity… A Critical Reading Workshop 1. Print a copy of your personal narrative. 2. In the left margin, bracket each section – intro, body, conclusion and label them. 3. Review the contents of each part. Is there a hook? Is the theme or idea clear? Does the introduction make your peers want to read on? Do you reflect at the end? Is your theme developed throughout? Use the slides as guides. Make additions or revisions. 4. Circle the sentence in the intro that declares your theme and label it. 5. Double underline the hook in your lead or intro. 6. Underline the sentences that discuss or return to the theme in the body of your piece. 7. Place a squiggly line under the sentences that discuss or reflect on the theme in your conclusion. 8. Check your topic sentences—in a word or two (in the margins) summarize the topic of each paragraph. 9. Check your topic and transition sentences – write a brief comment near each explaining why that sentence (the first) makes readers want to continue or how it (the last of each paragraph) smoothly connects to the next paragraph. 10. Place a star at the start of any sentence that you think will help readers connect to your topic or ideas. The Final Steps… While critically reading your essay, you probably noticed weak spots and areas that need development. Maybe you noticed editing errors. Revise and make corrections. Note those changes by writing a brief paragraph about what you changed, added, deleted and why, or by highlighting the changes in your essay. Hand in your essay, the one with all the markings on it and the revised copy if you made revisions and corrections. Credit for this workshop is based on completing the above (this slide and previous) and the reflective evaluation on the next slide. Workshop Evaluation Essay Structure Review A WORKSHOP OF THE JCC LANGUAGE, LITERATURE & ARTS DEPARTMENT Now that you have spent some time in this workshop, answer the following questions: What new ideas were presented or what ideas were useful reminders (since this should be a review for most students)?? What information or strategies did you find most helpful and why? What do you want to learn more about? How will you use specific information presented here to revise and edit your upcoming papers? This evaluation, along with your activities from this workshop serve to verify that you completed the workshop Essay Structure Review. Please include this evaluation along with the work from the activity in this workshop and turn in to your writing instructor as proof of completion.

© Copyright 2026