Cardiometabolic Syndrome & Dr Dhafir A. Mahmood Dr. Nabil Sulaiman

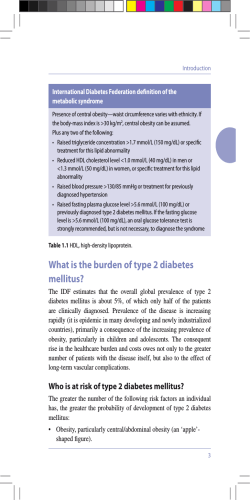

Cardiometabolic Syndrome Dr. Nabil Sulaiman HOD Family and Community Medicine, Sharjah University and University of Melbourne & Dr Dhafir A. Mahmood Consultant Endocrinologist Al- Qassimi & Al-Kuwait Hospital Sharjah Agenda • • • • • • • • • History & Definition Clustering component of Metabolic Syndrome Cardiovascular disease worldwide Global cardiometabolic risks Abdominal obesity prevalence ( National & International ) Intra Abdominal Adiposity & associated risks Targeting Cardiometabolic Risk factors Multiple Risk Factor management A Critical Look at the Metabolic Syndrome Metabolic Syndrome (History) • • • 1923 - Kylin first to describe the clustering of hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperuricemia 1936 - Himsworth first reported Insulin insensitivity in diabetics 1965 - Yalow and Berson developed insulin assay and correlated insulin levels & glucose lowering effects in resistant and non-resistant individuals Metabolic Syndrome History (cont.) • • • 1988 - Reaven in his Banting lecture at the ADA meeting coined the term Syndrome X and brought into focus the clustering of features of Metabolic Syndrome Reaven now prefers the name, InsulinResistance Syndrome - feels insulin resistance is the common denominator for Metabolic Syndrome Literature now extensive Other Names Used: • • • • • • • • Syndrome X Cardiometabolic Syndrome Cardiovascular Dysmetabolic Syndrome Insulin-Resistance Syndrome Metabolic Syndrome Beer Belly Syndrome Reaven’s Syndrome etc. Clustering of Components: • • • • • Hypertension: BP. > 140/90 Dyslipidemia: TG > 150 mg/ dL ( 1.7 mmol/L ) HDL- C < 35 mg/ dL (0.9 mmol/L) Obesity (central): BMI > 30 kg/M2 Waist girth > 94 cm (37 inch) Waist/Hip ratio > 0.9 Impaired Glucose Handling: IR , IGT or DM FPG > 110 mg/dL (6.1mmol/L) 2hr.PG >200 mg/dL(11.1mmol/L) Microalbuninuria (WHO) Necessary Criteria to Make Diagnosis • WHO: • • Impaired G handling + 2 other criteria. – Also requires microalbuminuria Albumen/ creatinine ratio >30 mg/gm creatinine IDF: – Require central obesity plus two of the other abnormalities NCEP/ATP III: – Require three or more of the five criteria What is cardiometabolic risk?* • • • Global cardiometabolic risk represents the overall risk of developing type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease (including MI and stroke), which is due to a cluster of modifiable risk factors/markers These include classical risk factors such as smoking, high LDL, hypertension, elevated blood glucose and emerging risk factors closely related to abdominal obesity (especially intra-abdominal adiposity), such as insulin resistance, low HDL, high triglycerides and inflammatory markers Cardiometabolic risk is based on the concept of risk continuum * working definition MI: myocardial infarction; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein Global cardiometabolic risk* * working definition Gelfand EV et al, 2006; Vasudevan AR et al, 2005 Despite therapeutic advances, CV disease remains the leading cause of death (USA) Data for 2002 No. of deaths (left axis) 400 300 Male Female % of all deaths (right axis) 200 100 0 Heart disease and stroke Cancer Accidents Chronic lower resp. disease 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 % All deaths (male + female) Number of deaths (thousands) 500 Diabetes National Center for Health Statistics, 2004 Substantial residual cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients The MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study % patients 30 Placebo Statin 20 Risk reduction=24% (p<0.0001) 19.8% of statin-treated patients had a major cardiovascular event by 5 years 10 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Year of follow-up Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group, 2002 Abdominal obesity has reached epidemic proportions worldwide Prevalence of abdominal obesity by region •US1 •South Europe2 •South Korea3 •Australia4 •South Africa5 •North Europe2 Men (%) Women (%) Total (%) 36.9 55.1 46.0 33.2 43.8 38.5 21.0 42.4 32.5 26.8 34.1 30.5 9.2 42.0 27.3 22.8 25.9 24.4 1. Ford ES et al, 2003; 2 Haftenberger M et al, 2002; 3. Kim MH et al 2004; 4. Cameron AJ et al, 2003; 5. Puoane T et al, 2002 Targeting Cardiometaboilc Risk Defining cardiometabolic Risk • • What is Abdominal Obesity ? Can be defined by Waist Circumference; ATP- III IDF Male: > 102 Cm. (> 42 Inch ) Male : > 94 Cm. ( > 37 Inch ) Female : > 88 Cm. (> 35 Inch ) Female : > 80 Cm. ( > 31.5 Inch ) Fat Topography In Type 2 Diabetic Subjects Intramuscular Subcutaneous Intrahepatic Intraabdominal FFA* TNF-alpha* Leptin* IL-6 (CRP)* Tissue Factor* PAI-1* Angiotensinogen* Abdominal obesity is linked to multiple cardiometabolic risk factors Patients with abdominal obesity often present with one or more additional cardiovascular risk factors (NCEP ATP III criteria) Cardiovascular risk factor Increased waist circumference Parameters Men Women Elevated LDL- Cholesterol Elevated triglycerides ≥102 cm (40 in) ≥88 cm (35 in) > 2.6 mmol/L (> 70 mg/d ) 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL) Low HDL- Cholesterol Men Women <1.03 mmol/L (<40 mg/dL) <1.30 mmol/L (<50 mg/dL) Hypertension BP 130/80 mm Hg Elevated fasting glucose 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL) HDL: high-density lipoprotein; BP: blood pressure National Cholesterol Education Panel/ Adult Treatment Panel III, 2002 Targeting Cardiometaboilc Risk Defining cardiometabolic Risk 86% 24% At least 1 additional CM risk factor 2 or more additional CM risk factors Abdominal obesity and increased risk of cardiovascular events The HOPE study Adjusted relative risk Waist circumference (cm): 1.4 Tertile 1 Men <95 Women <87 Tertile 2 Tertile 3 95–103 >103 87–98 >98 1.29 1 0.8 1.27 1.17 1.2 1 1.16 1 CVD death 1.35 1.14 1 MI All-cause deaths Adjusted for BMI, age, smoking, sex, CVD disease, DM, HDL-cholesterol, total-C; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MI: myocardial infarction; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol Dagenais GR et al, 2005 Abdominal obesity increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes 24 Relative risk 20 16 12 8 4 0 <71 71–75.9 76–81 81.1–86 86.1–91 91.1–96.3 >96.3 Waist circumference (cm) Carey VJ et al, 1997 Abdominal obesity is linked to an increased risk of coronary heart disease Waist circumference has been shown to be independently associated with increased age-adjusted risk of CHD, even after adjusting for BMI and other cardiovascular risk factors 3.0 Relative risk 2.5 p for trend = 0.007 2.31 2.44 2.06 2.0 1.5 1.27 1.0 0.5 0.0 <69.8 69.8<74.2 74.2<79.2 79.2<86.3 86.3<139.7 Quintiles of waist circumference (cm) CHD: coronary heart disease; BMI: body mass index Rexrode KM et al, 1998 Diabetes in the new millennium Interdisciplinary problem Diabetes Diabetes in the new millennium Interdisciplinary problem OBESITY Diabetes in the new millennium Interdisciplinary problem DIAB ESITY Targeting Cardiometabolic Risk Linked Metabolic Abnormalities: • Impaired glucose handling/ insulin • • • • • • • resistance Atherogenic dyslipidemia Endothelial dysfunction Prothrombotic state Hemodynamic changes Proinflammatory state Excess ovarian testosterone production Sleep-disordered breathing Resulting Clinical Conditions: • Type 2 diabetes • Essential hypertension • Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) • Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease • Sleep apnea • Cardiovascular Disease (MI, PVD, Stroke) • Cancer (Breast, Prostate, Colorectal, Liver) Multiple Risk Factor Management • Obesity • Glucose Intolerance • Insulin Resistance • Lipid Disorders • Hypertension • Goals: Minimize Risk of Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Glucose Abnormalities: • • • IDF: – FPG >100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol. L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes WHO: – Presence of diabetes, IGT, IFG, insulin resistance ATP III: – FBS >110 mg/dL, <126 mg/dL (6.1-7.1 mmol/L ) – (ADA: FBS >100 mg/dL [ 5.6 mmol/L ]) Hypertension: • • • IDF: – BP >130/85 or on Rx for previously diagnosed hypertension WHO: – BP >140/90 NCEP ATP III: – BP >130/80 Dyslipidemia: • • • IDF: – Triglycerides - >150mg/dL (1.7 mmol /L) – HDL - <40 mg/dL (men), <50 mg/dL (women) WHO: – Triglycerides - >150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) – HDL - <35 mg/dL (men), >39 mg/dL) women ATP III: – Same as IDF Screening/Public Health Approach • • Public Education Screening for at risk individuals: – Blood Sugar/ HbA1c – Lipids – Blood pressure – Tobacco use – Body habitus – Family history Life-Style Modification: Is it Important? • • Exercise – Improves CV fitness, weight control, sensitivity to insulin, reduces incidence of diabetes Weight loss – Improves lipids, insulin sensitivity, BP levels, reduces incidence of diabetes • Goals: Brisk walking - 30 min./day 10% reduction in body wt. Smoking Cessation / Avoidance: • • • A risk factor for development in children and adults Both passive and active exposure harmful A major risk factor for: – insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome – macrovascular disease (PVD, MI, Stroke) – microvascular complications of diabetes – pulmonary disease, etc. Diabetes Control - How Important? • • • • • • For every 1% rise in Hb A1c there is an 18% rise in risk of cardiovascular events & a 28% increase in peripheral arterial disease Evidence is accumulating to show that tight blood sugar control in both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes reduces risk of CVD Goals: FBS - premeal <110, postmeal <180. HbA1c <7% Overcome Insulin Resistance/ Diabetes: • • Insulin Sensitizers: – Biguanides - metformin – PPAR α, γ & δ agonists – Glitazones, Gltazars Rosiglitazon, Pioglitazon – Can be used in combination Insulin Secretagogues: – Sulfonylurea - glipizide, glyburide, glimeparide, glibenclamide – Meglitinides - repaglanide, netiglamide BP Control - How Important? • • • MRFIT and Framingham Heart Studies: – Conclusively proved the increased risk of CVD with long-term sustained hypertension – Demonstrated a 10 year risk of cardiovascular disease in treated patients vs non-treated patients to be 0.40. – 40% reduction in stroke with control of HTN Precedes literature on Metabolic Syndrome Goal: BP.<130/80 Lipid Control - How Important? • Multiple major studies show 24 - 37% • reductions in cardiovascular disease risk with use of statins and fibrates in the control of hyperlipidemia. Goals: LDL <100 mg/dL (<3.0 mmol /l) (high risk <70 mg/dL- <2.6 mmol/L) TG <150 mg% (<1.7 mmol /l) HDL >40 mg% (>1.1 mmol /l) Medications: • • • Hypertension: – ACE inhibitors, ARBs – Others - thiazides, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, alpha blockers – Central acting Alfa agonist : Moxolidin Dylipidemia: – Statins, Fibrates, Niacin Platelet inhibitors: – ASA, clopidogrel A Critical Look at the Metabolic Syndrome • • • Is it a Syndrome?* “…too much clinically important information is missing to warrant its designations as a syndrome.” Unclear pathogenesis, Insulin resistance may not underlie all factors, & is not a consistent finding in some definitions. CVD risks associated with metabolic syndrome has not shown to be greater than the sum of it’s individual components. *ADA & EASD A Critical Look at the Metabolic Syndrome • “Until much needed research is completed, • clinicians should evaluate and treat all CVD risk factors without regard to whether a patient meets the criteria for diagnosis of the ‘metabolic syndrome’.” The advice remains to treat individual risk factors when present & to prescribe therapeutic lifestyle changes & weight management for obese patients with multiple risk factors. Individual metabolic abnormalities among Qatari population according to gender (Musallam et al 08) Men (n = 405) Women (n=412) Variable n(%) ATP III n(%) p-Value Abdominal obesity 227(56.0) 308(74.8) <0.001 Hypertension 143(35.3) 156(37.9) 0.448 Diabetes 77(19.0) 107(26.0) 0.017 Hypertriglyceridemia 113(27.9) 83(20.1) 0.009 Low HDL 95(23.5) 121(29.4) 0.055 Individual metabolic abnormalities among Qatari population according to gender No of components of ATP III Men (n = 405) Variable n(%) n(%) Women (n=412) p-Value None 88(21.7) 74(18.0) – One 103(25.4) 100(24.3) Two 125(30.9) 111(26.9) – Three or more 89(22.0) 127(30.8) – 0.033 Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with Metabolic Syndrome according to (ATP III criteria) Age Female gender Odds ratio 95% CI p-Value 1.07 1.05–1.09 <0.001 1.86 1.30–2.67 0.001 Body Mass Index 1.05 1.02–1.07 <0.001 Fam his of DM 1.66 1.12–2.44 0.011 Smoking 3.27 1.63–6.55 0.001 Prevalence of MeS in different Countries Country Year Sample Prevalence (%) Arab Americans 2003 542 23 Oman 2001 1419 21 Jordan 2002 1121 36 Saudi Arabia 2004 2250 20.8 Palestine 1998 Qatar 2007 817 27.6 Turkey 2004 1637 33.4* Iran ? 10368 33.7 * Crude rates 17* Mussallam et al. Int J Food Safety and PH 2008 Prevalence of MeS in different Countries Country Year Sample Prevalence (%) USA 2005 2002 34* Greece 2005 1419 21 South Australia 2005 4060 15.3 S. Korea 2001 40,698 6.8 China 2000 2776 10.2* Turkey 2004 1637 33.4* Chennai India 2003 475 41* Qatar 2001 817 27.6 * Crude rates Mussallam et al. Int J Food Safety and PH 2008 Determinants and dynamics of the CVD Epidemic in the developing Countries • • • • • Data from South Asian Immigrant studies Excess, early, and extensive CHD in persons of South Asian origin The excess mortality has not been fully explained by the major conventional risk factors. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance highly prevalent. (Reddy KS, circ 1998). Central obesity, ↑triglycerides, ↓HDL with or without glucose intolerance, characterize a phenotype. genetic factors predispose to ↑lipoprotein(a) levels, the central obesity/glucose intolerance/dyslipidemia complex collectively labeled as the “metabolic syndrome” Determinants and dynamics of the CVD epidemic in the developing countries Other Possible factors • Relationship between early life characteristics and susceptibility to NCD in adult hood ( Barker’s hypothesis) (Baker DJP,BMJ,1993) – Low birth weight associated with increased CVD – Poor infant growth and CVD relation • Genetic–environment interactions (Enas EA, Clin. Cardiol. 1995; 18: 131–5) - Amplification of expression of risk to some environmental changes esp. South Asian population) - Thrifty gene (e.g. in South Asians) CVD epidemic in developing & developed countries. Are they same? • • • • • Urban populations have higher levels of CVD risk factors related to diet and physical activity (overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes) Tobacco consumption is more widely prevalent in rural population The social gradient will reverse as the epidemics mature. The poor will become progressively vulnerable to the ravages of these diseases and will have little access to the expensive and technology-curative care. The scarce societal resources to the treatment of these disorders dangerously depletes the resources available for the ‘unfinished agenda’ of infectious and nutritional disorders that almost exclusively afflict the poor Burden of CVD in Pakistan Coronary heart disease • • Mortality statistics Specific mortality data ideal for making comparisons with other countries are not available Inadequate and inappropriate death certification, and multiple concurrent causes of death Central obesity: a driving force for cardiovascular disease & diabetes Front Back “Balzac” by Rodin Developing A New Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome: IDF Objectives Needs: • To identify individuals at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease (and diabetes) • • To be useful for clinicians To be useful for international comparisons International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Consensus Definition 2005 The new IDF definition focusses on abdominal obesity rather than insulin resistance Why people physically inactive? • • • • Lack of awareness regarding the of physical activity for health fitness and prevention of diseases Social values and traditions regarding physical exercise (women, restriction). Non-availability public places suitable for physical activity (walking and cycling path, gymnasium). Modernization of life that reduce physical activity (sedentary life, TV, Computers, tel, cars). Insulin Resistance: Associated Conditions Prevalence (%) Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome Among US Adults NHANES 1988-1994 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Men Women 20-29 30-39 Ford E et al. JAMA. 2002(287):356. 40-49 50-59 60-69 > 70 Age (years) 1999-2002 Prevalence by IDF vs. NCEP Definitions (Ford ES, Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2745-9) (unadjusted, age 20+) NCEP : 33.7% in men and 35.4% in women IDF: 39.9% in men and 38.1% in women Prevention of CVD • There is an urgent need to establish appropriate research studies, increase awareness of the CVD burden, and develop preventive strategies. • Prevention and treatment strategies that have been proven to be effective in developed countries should be adapted for developing countries. • Prevention is the best option as an approach to reduce CVD burden. • Do we know enough to prevent this CVD Epidemic in the first place. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Consensus Definition 2005 The new IDF definition focusses on abdominal obesity rather than insulin resistance International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Consensus Definition 2005 Central Obesity Waist circumference – ethnicity specific* – for Europids: Male > 94 cm Female > 80 cm plus any two of the following: Raised triglycerides > 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality Reduced HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in males < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in females or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality Raised blood pressure Systolic : > 130 mmHg or Diastolic: > 85 mmHg or Treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension Raised fasting plasma glucose Fasting plasma glucose > 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or Previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes If above 5.6 mmol/L or 100 mg/dL, OGTT is strongly recommended but is not necessary to define presence of the syndrome. Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome: 2005 Stop smoking Oral hypoglycaemics Insulin Statins & Fibrates ACEI &/or A2 receptor blockers Diet, Exercise, Lifestyle change Aspirin CB1 Receptor Blocker Antihypertensives Recommendations for treatment Primary management for the Metabolic Syndrome is healthy lifestyle promotion. This includes: • moderate calorie restriction (to achieve a 5-10% loss of body weight in the first year) • moderate increases in physical activity • change dietary composition to reduce saturated fat and total intake, increase fibre and, if appropriate, reduce salt intake. Management of the Metabolic Syndrome • Appropriate & aggressive therapy is essential for reducing patient risk of cardiovascular disease • Lifestyle measures should be the first action • Pharmacotherapy should have beneficial effects on – – – – Glucose intolerance/diabetes Obesity Hypertension Dyslipidaemia • Ideally, treatment should address all of the components of the syndrome and not the individual components Summary: new IDF definition for the Metabolic Syndrome The new IDF definition addresses both clinical and research needs: provides a simple entry point for primary care • physicians to diagnose the Metabolic Syndrome providing an accessible, diagnostic tool • suitable for worldwide use, taking into account ethnic differences establishing a comprehensive ‘platinum • standard’ list of additional criteria that should be included in epidemiological studies and other research into the Metabolic Syndrome Lifestyle modification • • • • Diet Exercise Weight loss Smoking cessation If a 1% reduction in HbA1c is achieved, you could expect a reduction in risk of: • • • 21% for any diabetesrelated endpoint 37% for microvascular complications 14% for myocardial infarction However, compliance is poor and most patients will require oral pharmacotherapy within a few years of diagnosis Stratton IM et al. BMJ 2000; 321: 405–412.

© Copyright 2026