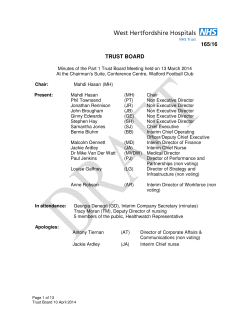

Best Practices for Community Health Needs Assessment and Implementation Strategy Development: