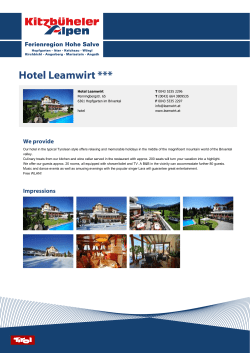

TOURISMOS reviewed) journal aiming to promote and enhance research in all... tourism, including travel, hospitality and leisure. The journal is published