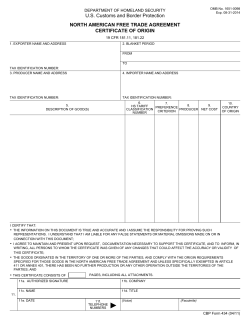

THE UNITED STATES-CENTRAL AMERICA- DOMINICAN REPUBLIC FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (CAFTA):