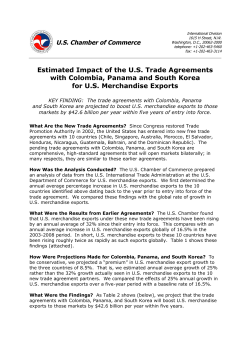

CRS Report for Congress The Dominican Republic-Central America-United