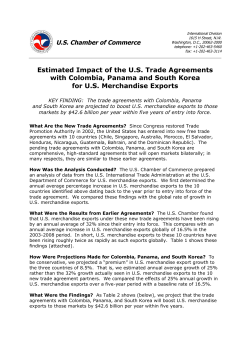

Document 42925