HanDeL soCietY of DaRtMoUtH CoLLege artistic director with

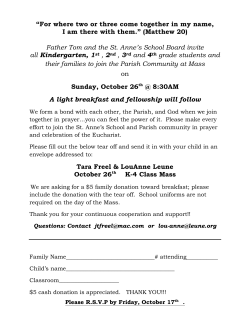

presents HANDEL SOCIETY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE Robert Duff artistic director and conductor with Elissa Alvarez soprano Erma Mellinger mezzo-soprano These performances are made possible in part by generous support from the Choral Arts Foundation of the Upper Valley (choralartsuv.org), the Gordon Russell 1955 Fund, the Glick Family Student Ensemble Fund and Friends of the Handel Society. Tuesday, November 18, 2014 • 7 pm Spaulding Auditorium • Dartmouth College program Schicksalslied, Op. 54 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Rhapsodie, Op. 53 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Gesang der Parzen, Op. 89 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Ave Maria, Op. 12 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) • intermission • Annelies James Whitbourn (b. 1963) 1. Introit-prelude 2. The capture foretold 3. The plan to go into hiding 4. The last night at home and arrival at the Annexe 5. Life in hiding 6. Courage 7. Fear of capture and the second break-in 8. Sinfonia (Kyrie) 9. The Dream 10. Devastation of the outside world 11. Passing of time 12. The hope of liberation and a spring awakening 13. The capture and the concentration camp 14. Anne’s meditation program notes Schicksalslied, Opus 54 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Johannes Brahms was born in Hamburg, Germany on May 7, 1833, and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. He composed Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny) around the same time as Alto Rhapsodie, completing it in May 1871; it was premiered in Karlsruhe on October 18 the same year. In addition to the mixed chorus, the score calls for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Late in the summer of 1868, after taking his father to Switzerland for a mountain holiday, Brahms visited his friends the Dietrichs in Oldenburg. While there, he specifically asked if they could visit the great shipbuilding works at Wilhelmshaven. Curiously, Brahms was fascinated by ships though he could rarely be induced to board one. On the morning scheduled for the visit, Brahms found himself awake before the rest of the family. Among the Dietrich family’s books, he found a volume of poems by Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1825), which he began reading. He told his hosts that he had been deeply moved by a poem entitled Hyperion’s Song of Destiny. Years later, in a memoir recalling his friendship with Brahms, Albert Dietrich wrote: “When, later in the day, after having wandered about and seen everything of interest, we sat down by the sea to rest, we discovered Brahms at a great distance, sitting alone on the beach and writing. These were the first sketches for Schicksalslied.” The text, reenacting the Classical fatalism of the Greeks, spoke to some central element in the composer’s own soul. Yet, despite the immediate reaction to the poem and the instant musical sketch, Brahms was unable to bring the work to completion until May 1871, nearly three years later. The problem may have lain in the structure of Hölderlin’s grim text: the poem is written in two parts—the first depicting the tranquil, eternal bliss of the gods in their abode of light, and the second contrasting it with the torments of humanity, driven by a blind destiny. However, Brahms did not want to end the music in such a negative mood. He considered simply repeating the opening words at the end, but was dissuaded from that course by the conductor Hermann Levi. Instead, Brahms concluded the piece with a tranquil orchestral statement of the opening music, thus rounding it off musically with a hint of consolation, while retaining the text’s original form. The music of the gods is luminous, sharply contrasted with the hard driven torments of mankind, especially the dramatic depiction of “water thrown from crag to crag,” followed by a sudden silence. The chorus ends on a note of resignation, but a shift from C minor to C major brings reconciliation. Rhapsodie, Opus 53 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Brahms composed Rhapsodie (Alto Rhapsody) in the autumn of 1869; the first performance took place in Jena on March 3, 1870. The score calls for a solo alto voice, four-part men’s chorus, and orchestra consisting of pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns, plus strings. On May 11, 1869, Clara Schumann had happy news to share with her good friend Brahms when he visited her in Baden-Baden: her 24-year-old daughter Julie had just become engaged. Brahms choked out a few words and, to Clara’s surprise, promptly disappeared. Perhaps only now did she understand some of the composer’s behavior during the previous half-dozen years. Described as an ethereal beauty, Julie evidently captivated Brahms as early as 1861, when he dedicated to her his Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 23. At the time Clara evidently regarded it simply as homage to her program notes CONTINUED family, because Robert, before his death, had been the young Brahms’ best friend and strongest proponent. Julie was a beautiful but frail angel, who often suffered from illness. Brahms felt a deep and growing affection for her, but his reaction was complicated by his role in helping to care for the family after Robert’s death. He became a kind of surrogate father to Julie, and his warm friendship with Clara—twenty years older than he—made her a cross between a mother figure and a fantasy lover. Combined with these emotional complexities was the fact that Brahms’ early experiences playing the piano in the brothels of Hamburg led him to view the sexual side of human relations as something essentially sordid. Julie herself occasionally felt some discomfort from the evident fervor of Brahms’ interest in her well-being, though he never let her know his feelings explicitly. have on his Psalter “a single tone perceptible to his ear,” which might “revive his heart.” Surely Brahms offered that prayer for himself. Goethe’s poem spoke to him with unusual directness, and he responded to it with shattering, personal music. Out of his sadness at realizing he had lost her, Brahms found words that perfectly expressed his emotional condition and set them to music in one of his most moving scores. He presented the work as an expression of his own struggle with loneliness. A week after Julie’s wedding on September 22, 1869, Brahms visited Clara and played for her the work he called his “bridal song.” Clara’s response (in her journal): “It is long since I remember being so moved by a depth of pain in words and music.” Gesang der Parzen, Opus 89 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Brahms composed the Gesang der Parzen (Song of the Fates) in 1882. In addition to the sixpart chorus (SAATBB), the score calls for two flutes (the second doubling piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and strings. The text that Brahms chose for what became one of his most personal expressions comprises the central part of a difficult poem of Goethe’s, Harzreise im Winter (Winter Journey Through the Harz Mountains). Of the poem’s 88 lines, Brahms set only about one quarter of the whole. Goethe’s poem was written after a 1777 visit to the Harz Mountains, where he met a correspondent of his, a misanthropic young fellow named Plessing, who had withdrawn from the world into the solitude of nature. Goethe’s poem describes one who goes “off apart,” praying that the Father of Love may The orchestral introduction shivers in its chilly Cminor depiction of the winter scene, interrupted by the alto soloist, who notices the solitary wanderer; she enters suddenly, as if overheard in the middle of a thought. A central section, actually an aria, describes the one who, having been scorned, now scorns all in return. The harmonic and rhythmic agitation of this section yields magically at the entrance of the men’s voices and a turn to a consoling C major and a warmly ardent melody praying for the reconciliation of the wanderer. Brahms completed Gesang der Parzen in 1882, at the age of 50, and never again returned to the medium of chorus and orchestra. He chose a strongly classicizing poem by the greatest master of German lyric, Goethe (it is, in fact, drawn from his poetic drama Iphigenia auf Tauris). Like his earlier setting of Hölderlin’s Schicksalslied, this text treats the gulf between the gods in the heights and mankind below, hapless victims of the Fates. As befits the darkness of the poem’s mood, Brahms creates a dark-colored choral sound in six parts, dividing the altos and basses into two parts each. The six-part chorus naturally falls into semi- program notes CONTINUED choruses of women’s or men’s voices, and Brahms exploits the possibilities of echoing one group against the other. The work is ascetic in its musical approach, avoiding showy florid passages and an easy consolation. Indeed, at the beginning of the final stanza of the text we expect, for a moment, the kind of turn to the major key that brings reconciliation in the Schicksalslied or the Alto Rhapsody—but here it does not happen. Brahms ends the final stanza resolutely in a dark and despairing close. Ave Maria, Op. 12 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Brahms composed Ave Maria in Detmold during the summer of 1858, for four-part women's voices with an accompaniment for either organ or orchestra. It premiered in a concert by Karl Grädener's ”Akademie" in Hamburg in December 1859. The orchestral alternative called for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons and horns, plus strings. As a young man, Brahms composed works for women's voices—whether chorus or solo voices often sung by choruses—for ensembles in towns where he lived and visited. These works were performed with delight by the female groups, and he eventually became the conductor of one such ensemble, greatly enriching the repertory for women's voices. Of all composers of the 19th-century, Brahms undertook the most detailed and extensive study of earlier music, studying in detail composers from at least the 16th-century onward, comparing editions, reading books on music theory and history, and comparing points in which they disagreed. He may fairly be regarded as the first significant composer who also showed great ability as a musicologist, a field that was just beginning to take its place in the world of music, though there were as yet no formal academic requirements for it. The lovely Ave Maria offers an homage to the flowing lines of Renaissance choral music, though no one would confuse it for actual 16th-century music. Its harmonies are entirely tonal, with modulations scarcely guessed at 300 years earlier, and the lightly contrapuntal lines are by no means as thorough-going as in the counterpoint of the earlier period. Its cool and gentle cantabile character shows that Brahms was already entirely at home laying out music for groups of voices, suggesting his future as one of the half dozen greatest composers for chorus of the entire romantic era. Steven Ledbetter Annelies James Whitbourn (b. 1963) Libretto by Menaie Challenger based on Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. Whitbourn composed Annelies during 2004 and 2005; the first performance occurred at the National UK Holocaust Memorial Day in Westminster Hall, London, on January 27, 2005. The full orchestration calls for solo soprano voice, mixed chorus, flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, two horns, three trombones, timpani, percussion, piano and strings. The following notes are provided by the composer: “If Anne could be with us tonight, I know she would shed tears of joy and pride, and she would be so happy—happy the way I remember when I saw her last.” These words were spoken by Bernd Elias, Anne Frank’s first cousin, before the first performance of Annelies. His is a remark that stops you in your tracks, because it is easy to forget that Annelies (Anne’s full name) was a real person, with friends and family, and not just a historical figure. She was a happy person, and a hugely talented girl. Today, she would be in her 80s had she lived. In her room in hiding, she had a photograph on her wall of Princess Elizabeth, now Queen Elizabeth II, one of the famous people she loved to admire. It is sobering to remember that the British monarch is several years her senior and program notes CONTINUED at the time of tonight’s concert still carries out her royal duties. Anne Frank should have been a younger contemporary of hers. Yet Anne Frank did not grow up. Her death has kept her an eternal child, and her diary continues to speak directly to children and adults today. She was a highly intelligent human being, full of perception and maturity, and her diary is a brilliant piece of writing in its own right. The fact that it sits within a story of such horror as the Holocaust makes its brilliance so painful. But at the time of writing the diary, Anne had not experienced the Holocaust first hand, though she was much more aware of it than her companions-in-hiding realized. By all accounts, she was always full of questions. One of the helpers, Miep Gies, who kept the supply of food to the Annexe flowing, recalls that Anne (whom she adored) used to follow her down the stairs at the end of each day’s visit and ask about what was really happening in the outside world. For example, she wanted to know the fate of the Jews she saw rounded up and arrested on the streets below. “I told her the truth,” Miep said. Anne knew what was happening. Yet none of the housemates, not even her own parents, realized the depth of her understanding. The side of her character she called her “better side” was hidden from sight and reserved only for the pages of her diary. It is these penetrating observations that form the basis of Melanie Challenger’s libretto. In Melanie, I saw qualities that reflect Anne Frank’s character, especially her penetrating understanding of other people. The idea for a choral work came from Melanie at a time when she had been working on a music project with children from war-torn Bosnia. She approached me with the idea, and we worked intensely together for almost three years. From the outset, we were clear that it was those remarkable observations that were to form the basis of this work. Squabbles within the Annexe, teenage romantic encounters and the like were all put aside, and the diary distilled into this sequence of beautiful, spiritually-charged texts. Melanie skillfully made a translation suitable for me, as a composer, to set to music. Rarely have I found a text so compelling and the inspiration for so much, simply as a document in its own right. But as time went on, and as I worked on the score, I also became more aware of Anne Frank as a contemporary person. Eventually, I came to meet her cousin Bernd, and later one of her school friends, of whom she speaks so often in the diary. These personal family links influenced the kind of piece it was destined to be, and at times it felt as though I were putting together the music for the family’s memorial event. It was to be a commemorative work, not only for Anne Frank, but for those by whose side she lived, those she watched with penetrating eyes, and those voiceless millions who shared her fate. Annelies Marie Frank died in the Bergen-Belsen camp, along with her sister Margot, having previously been held at Auschwitz. By that time, she assumed her mother was dead, and she believed her father was dead too. In fact, he survived, and Anne’s friend Hannah Goslar—the last person we know to have seen her alive— always wondered whether Anne would have found the strength to live had she known her beloved father was not dead. The legacy of her death has been remarkable. Anne always intended to publish her diary, and that wish has been fulfilled in a way she cannot have imagined. It has been a privilege to work on these texts. The world premiere in London—in the original orchestral version—was beautifully conducted by program notes CONTINUED the American conductor Leonard Slatkin. Three movements of the work were performed at the UK’s National Holocaust Day event for the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. It was given in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, whose face Anne Frank had gazed at on the wall of her little attic room all those years ago, and of five hundred survivors of the Holocaust, their families, and several hundred others. The setting was Westminster Hall, an enormous eleventh century hall within the Houses of Parliament in London. It was a cold January day, and the hall was appropriately cold for the occasion. The work was introduced by Anne’s school friend, Hannah Gosler. It is my hope that, in the end, it is the text itself that finds a way to leave the indelible mark of that young girl whose wisdom and perception can teach us all. James Whitbourn text and translations Schicksalslied Friedrich Hölderlin Ihr wandelt droben im Licht, Auf weichem Boden, selige Genien! Glänzende Götterlüfte Rühren euch leicht, Wie die Finger der Künstlerin Heilige Saiten. You walk above in the light on soft ground, blessed spirits! Glistening divine breezes Touch you lightly, just as the fingers of the fair artist play the sacred harpstrings. Schicksallos, wie der schlafende Säugling, atmen die Himmlischen; Keusch bewahrt In bescheidener Knospe Blühet ewig Ihnen der Geist, Und die seligen Augen Blicken in stiller, Ewiger Klarheit. Free from fate, like the sleeping infant, celestial spirits breathe; chastely protected in modest buds, their spirit blooms forever, and their blessed eyes gaze in calm, eternal clarity. Doch uns ist gegeben Auf keiner Stätte zu ruhn; Es schwinden, es fallen Die leidenden Menschen Blindlings von einer Stunde zur andern, Wie Wasser von Klippe Zu Klippe geworfen, Jahrlang ins Ungewisse hinab. Yet we are given no place to rest; we suffering humans vanish and fall blindly one hour to the next, like water flung from cliff to cliff endlessly down into the unknown. text and translations CONTINUED Gesang der Parzen Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Es fürchte die Götter Das Menschengeschlecht! Sie halten die Herrschaft In ewigen Händen, Und können sie brauchen, Wie’s ihnen gefällt. Mankind should fear the gods! They hold dominion in their eternal hands, and can use it as they please. Der fürchte sie doppelt Den je sie erheben! Auf Klippen und Wolken Sind Stühle bereitet Um goldene Tische. Any whom they exalt should fear them doubly! On cliffs and clouds thrones stand ready around golden tables. Erhebet ein Zwist sich, So stürzen die Gäste, Geschmäht und geschändet In nächtliche Tiefen, Und harren vergebens, Im Finstern gebunden, Gerechten Gerichtes. If dissension arises, the guests are hurled down, despised and disgraced, into the nocturnal depths, waiting there in vain, bound in darkness, for just judgment. Sie aber, sie bleiben In ewigen Festen An goldenen Tischen. The gods, however, continue the eternal feasts at the golden tables. Sie schreiten vom Berge Zu Bergen hinüber: Aus Schlünden der Tiefe Dampft ihnen der Atem Erstickter Titanen, Gleich Opfergerüchen, Ein leichtes Gewölke. They stride over mountains from peak to peak: from the abysses of the deep the breath of suffocated Titans steams up to them like scents of sacrifices, a light cloud. Es wenden die Herrscher Ihr segnendes Auge Von ganzen Geschlechtern Und meiden, im Enkel Die ehmals geliebten, Still redenden Züge Des Ahnherrn zu sehn. The rulers avert their blessing-bestowing eyes from entire generations, and avoid seeing, in the grandchild, the once-loved, silently still speaking features of the ancestor. So sangen die Parzen; Thus sang the Fates. text and translations CONTINUED Es horcht der Verbannte, In nächtlichen Höhlen Der Alte die Lieder, Denkt Kinder und Enkel Und schüttelt das Haupt. The old, banished one listens to the songs in his nocturnal caverns, thinks of his children and grandchildren, and shakes his head. Rhapsodie Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Aber abseits wer ist’s? Im Gebüsch verliert sich der Pfad. Hinter ihm schlagen Die Sträuche zusammen, Das Gras steht wieder auf, Die Öde verschlingt ihn. But there, apart, who is it? His path is lost in the thicket; behind him the bushes close together; the grass rises again; the wasteland devours him. Ach, wer heilet die Schmerzen Des, dem Balsam zu Gift ward? Der sich Menschenhaß Aus der Fülle der Liebe trank? Erst verachtet, nun ein Verächter, Zehrt er heimlich auf Seinen eigenen Wert In ungenugender Selbstsucht. Alas, who will heal the pains of him whose balm turned to poison? Who drank his hatred of humankind from the fullness of love? First despised, now a despiser, he secretly consumes his own worth in insatiable vanity. Ist auf deinem Psalter, Vater der Liebe, ein Ton Seinem Ohre vernehmlich, So erquicke sein Herz! Öffne den umwölkten Blick Über die tausend Quellen Neben dem Durstenden In der Wüste! If there be on your psaltery, Father of love, a tone that his ear can hear, then restore his heart! Open the clouded view of the thousand springs around him, who thirsts in the desert! Ave Maria Ave Maria, gratia plena: Dominus tecum, benedicta tu in mulieribus, et benedictus fructus ventris tui, Jesus. Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Sancta Maria, Mater Dei ora pro nobis. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us. Annelies Due to the length of the libretto, supertitles will be provided. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Elissa Alvarez soprano is an avid interpreter of recital, concert and operatic repertoire. Noted by the Boston Globe for her “intensely lyrical” singing, Ms. Alvarez is a great advocate of living composers and has been involved in numerous premieres in recent seasons. She appeared in concert and on recording as Mary Magdalene in the world premiere of Emmy-nominated composer Kareem Roustom’s acclaimed mystical oratorio, The Son of Man with Boston’s Coro Allegro, a performance for which they received Chorus America’s 2012 ASCAP/Alice Parker Award. Ms. Alvarez holds a doctorate of musical arts from Boston University. Erma Mellinger mezzo-soprano, vocal coach has been a principal artist with many opera companies across the United States, including the Cleveland Opera, the Florida Grand Opera, the Dallas Opera, the Sarasota Opera, the Chautauqua Opera, the Fresno International Grand Opera, Opera North, the Pittsburgh Opera Theater, and the Shreveport Opera. Her roles, in over thirty operas, include: Cherubino in Le Nozze di Figaro, Dorabella in Così fan tutte, Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni, Idamante in Idomeneo, Empress Ottavia in L’incoronazione di Poppea, Nicklausse in Les contes d’Hoffmann, Preziosilla in La Forza del Destino, Prince Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus, Prince Charming in Cendrillon, Martha in Faust, Tisbe in La Cenerentola and Berta in Il barbiere di Siviglia. Hailed for her “rich, vibrant, creamy voice,” Ms. Mellinger is also at home on the concert and recital stage. She has appeared as soloist with many major orchestras, including the Fort Wayne Philharmonic, the Monterey Symphony, the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, the Florida Symphony Orchestra, the Westfield Symphony, the New Hampshire Philharmonic Orchestra and the Vermont Symphony Orchestra. She has given solo recitals sponsored by the Buffalo Opera, the Adirondack Ensemble, Chamber Works at Dartmouth College, and Classicopia. Ms. Mellinger graduated first in her class from Northwestern University, where she received her Bachelor of Music Degree in Vocal Performance. She earned her Master of Music Degree from Eastman School of Music, where she also received honors in performance and teaching. She is a frequent guest artist on the Dartmouth campus performing regularly with the Handel Society, the Wind Symphony and the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra. Ms. Mellinger began teaching voice at Dartmouth in 1996. Robert Duff conductor is the artistic director of the Handel Society of Dartmouth College, and teaches courses in music theory and musicianship in the Music Department. Before coming to Dartmouth in 2004, Dr. Duff served on the faculties of Pomona College, Claremont Graduate University, and Mount St. Mary’s College, and as the Director of Music for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, where he directed the music programs for nearly 300 parishes. He holds degrees in conducting, piano and voice from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Temple University, and the University of Southern California, where he earned a doctorate of musical arts in 2000. An active commissioner of new music, Dr. Duff has given several world premieres of works for both orchestral and choral forces. He has served as Councilor to the New Hampshire Council on the Arts, and is the past President of the Eastern Division of the American Choral Directors Association. Handel Society of Dartmouth College is the oldest student, faculty, staff and community organization in the United States devoted to the performance of choral-orchestral major works. The Society was founded in 1807 by Dartmouth faculty and students to “promote the cause of true and genuine sacred music.” Led by John Hubbard, Dartmouth Professor of Mathematics and Philosophy, the Society sought to advance ABOUT THE ARTISTs CONTINUED the works of Baroque masters through performance. Members of the Society believed the grand choruses of George Frideric Handel exemplified their goals and thus adopted his name for their group. Since its inception, the Handel Society has grown considerably in size and in its scope of programming. Today comprising 100 members drawn from the Dartmouth student body, faculty and staff, and the Upper Valley community, the Society performs two concerts a year of major works both old and new. For more information about the Handel Society, call 603/646-3414 or visit our website at www.handelsociety.org. Annemieke Spoelstra collaborative pianist was born in Kampen, The Netherlands, and started piano lessons with Joke Venhuizen at age seven. She studied classical piano at the Conservatory in Zwolle, The Netherlands, with Rudy de Heus, earning her degrees Docerend and Uitvoerend Musicus (Bachelor and Masters as Performing Artist) for soloist, chamber music and art song accompaniment. She later studied Art Song Accompaniment at the Sweelinck Conservatory in Amsterdam as a duo with German tenor Immo Schröder. She has often been invited to serve as collaborative artist at conservatories and national and international competitions. At age twenty-one, Spoelstra was First Prize winner at the Dutch National competition Young Music Talent Nederland for best accompanist. She was praised for her touch and coloring. In 1997 she was First Prize winner for Music Student of the Year for her final recital. The jury report wrote, “She shows great intellect in music pedagogy and is a sensible, great performer, with wellbalanced programs.” In 2001 she was a finalist in Paris at the international Nadia and Lili Boulanger competition. Since January 2004, she has been a US resident living in Vermont. She performs solo, teaches piano at St. Michael’s College and at her studio, and coaches vocalists and instrumentalists for auditions, competitions and performance. Spoelstra serves as accompanist for the chorale at St. Michael’s College, and has accompanied the Vermont Youth Orchestra Choruses and the Thetford Chamber Singers. She has performed concerts in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Poland and the USA. Acknowledgments Many thanks are extended to the Board of Directors of the Handel Society and the numerous members-at-large of the organization, community and student, for their fine work on behalf of the Handel Society. We thank the Choral Arts Foundation of the Upper Valley and the Friends of the Handel Society (Dartmouth College alumni, past and present community Handel Society members, and regional audience supporters of the Handel Society) for the financial support of the Handel Society’s concert season. Additional thanks to Hilary Pridgen of The Trumbull House for providing accommodations for guest soloists. The Trumbull Bed & Breakfast, 40 Etna Road, Hanover, NH 03755; (603) 643-2370 or toll-free (800) 651-5141; www.trumbullhouse.com For information on the Choral Arts Foundation of the Upper Valley, please contact: Choral Arts Foundation of the Upper Valley P.O. Box 716, Hanover, NH 03755 [email protected] handel society of dartmouth college Robert Duff conductor Erma Mellinger vocal coach Annemieke Spoelstra collaborative pianist Soprano Megan Becker Alice Bennett Eugenia Braasch* Susan Cancio-Bello Daniela Childers ‘16 Meg Darrow Williams Else Drooff ‘18 Karen Endicott Emily Golitzin ‘18 Mardy High Kendall Hoyt* Ling Jing ‘15 Alana Juric ‘18 Ashley Kolste Bronwyn Lloyd ‘17 Sharon McMonagle Jaclyn Pageau ‘18 Katie Price GR Mary Quinton-Barry* Rebekah Schweitzer Jo Shelnutt Gretchen Twork* Kaitlin Whitehorn ‘16 Alto Elizabeth Adams Anna Alden Carissa Aoki GR* Carol Barr Andrea N. Brown Kathy Christie Helen Clark* Joanne Coburn* Johanna Evans ‘11 Anne Felde Lindsey Fera Linda L. Fowler Anna Gado Ridie Wilson Ghezzi Ellen Irwin ‘14 Nicole Johnson Emily Jones Kristi Medill Cathleen E. Morrow Rosemary Orgren* Bonnie Robinson* Margaret Robinson Zoe Sands ‘18 Jacqueline Smith Elisebeth Sullivan* Averill Tinker Kristin Winkle ‘18 Tenor Gary E. Barton* Brian Clancy Michael Cukan ˇ Scot Drysdale Jon Felde Henry Higgs Rob Howe James King Mark Nelson David Thron Richard Waddell* Adam Weinstein ‘98* Pat Yealy Bass John Archer Kenneth Bauer* William Braasch Stephen Campbell David C. Clark John Cofer '15 Trevor Davis '18 Raul Del Cid '17 Charles Faulkner Robert Fogg Paul Wilder Frazel ‘15 Tom Gray Evan J. Griffith ‘15 Ethan Klein ‘16 Myung Chang Lee ‘18 Daniel Meerson Andrew Nalani ‘16 Jimmy Ragan ‘16 David T. Robinson Cameron Stevens Sam Stratton ‘15 Jarrett Taylor ‘18 GR=Graduate Student *Member, Handel Society Board of Directors orchestra Violin 1 Elizabeth Young concertmaster Zoya Tsvetkova Letitia Quante Leah Zelnick Jane Kittredge Jesse Irons Sarah Washburn Violin 2 Bozena O’Brien principal Rachel Handman Asuka Usui Kay Rooney Matthews Melanie Dexter Laura Markowitz Viola Marcia Cassidy principal Russell Wilson Jason Fisher Consuelo Sherba Leslie Sonder Cello Emily Taubl principal Perri Morris Rachel Gawell Cherry Kim Bass Phil Helm principal Paul Horak Trumpet Geoffrey Shamu principal Samantha Glazier Flute Melissa Mielens principal Anne Janson Trombone Brittany Lasch principal Robert Hoveland Gabriel Langfur Oboe Margaret Herlehy principal Ann Greenawalt Clarinet Matthew Marsit principal Marguerite Levin Bassoon Janet Polk principal Rebecca Eldredge Horn Michael Lombardi principal Patrick Kennelly Chris Mortensen Joy Worland Tuba Takatsugu Hariwara principal Timpani Jeremy Levine principal Percussion Nicola Cannizzaro principal Charles Kiger Mike Singer Piano Annemieke Spoelstra DARTMOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ANTHONY PRINCIOTTI conductor sat FEB 28 8 pm SpaulDing auDitOriuM The Hop’s resident orchestra performs works by Borodin and Dvorˇák as well as Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with soloist Lulu Chang ‘15. HANDEL SOCIETY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE ROBERT DUFF conductor sat may 16 8 pm SpaulDing auDitOriuM The nation’s oldest town-gown choral society performs Verdi’s Requiem with soloists Othalie Graham soprano, Margaret Lattimore mezzo soprano, Brian Cheney tenor and Kyle Albertson bass. For tickets or more info call the Box Office at 603.646.2422 or visit hop.dartmouth.edu. Sign up for weekly HopMail bulletins online or become a fan of “Hopkins Center, Dartmouth” on Facebook Hopkins Center Management Staff Jeffrey H. James ‘75a Howard Gilman Director Marga Rahmann Associate Director/General Manager Joseph Clifford Director of Audience Engagement Jay Cary Business and Administrative Officer Bill Pence Director of Hopkins Center Film Margaret Lawrence Director of Programming Joshua Price Kol Director of Student Performance Programs HOPKINS CENTER BOARD OF OVERSEERS Austin M. Beutner ’82 Kenneth L. Burns H’93 Barbara J. Couch Allan H. Glick ’60, T’61, P’88 Barry Grove ’73 Caroline Diamond Harrison ’86, P’16 Kelly Fowler Hunter ’83, T’88, P’13, P’15 Richard P. Kiphart ’63 Please turn off your cell phone inside the theater. R Robert H. Manegold ’75, P’02, P’06 Nini Meyer Hans C. Morris ’80, P’11, P’14 Chair of the Board Robert S. Weil ’40, P’73 Honorary Frederick B. Whittemore ’53, T’54, P’88, P’90, H’03 Jennifer A. Williams ’85 Diana L. Taylor ’77 Trustee Representative Assistive Listening Devices available in the lobby. D A RT M O UTH RECYCLES If you do not wish to keep your playbill, please discard it in the recycling bin provided in the lobby. Thank you.

© Copyright 2026