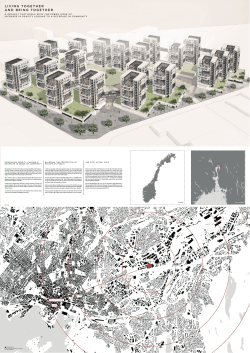

Here - ProjectOsloRegion