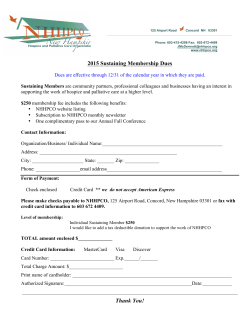

English version