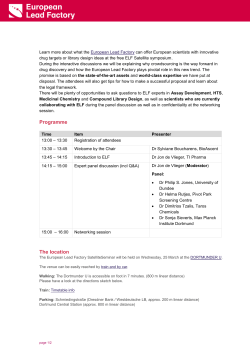

Anna-Riikka`s MacBook Air`s conflicted copy 2016-08-29