Date and/or place of burial or disposition of cremated remains

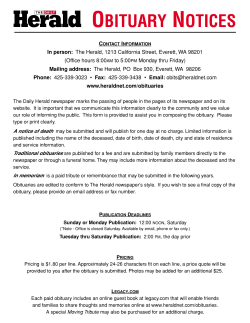

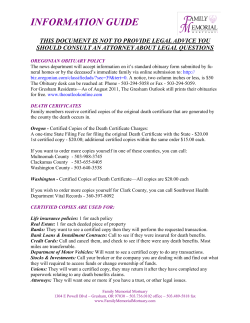

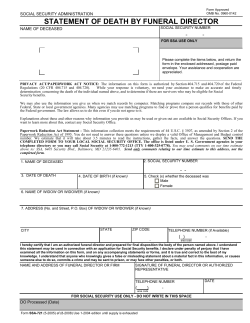

WORKBOOK Death Records B Y D AV I D A . F R Y X E L L 3 WHEN RESEARCHING YOUR ancestor’s story, many genealogy experts recommend beginning with the final chapter—the record of an ancestor’s death. After all, a death certificate or other death record represents the most recent evidence of your ancestor’s life. This workbook will show you what’s in a death record, how to find one, and what other records include the death information you seek. We’ll also provide a worksheet you can fill in (and photocopy, if need be) to map out your death records search. Clues in death records The death certificate is considered a primary source for the details of an ancestor’s passing, such as the date, place and time of death. It also can be a rich secondary source for an ancestor’s life, providing clues to everything from birth and parents to spouse and last residence. Such information on death records is considered less reliable because it comes from the informant—typically a spouse, child or other family member. Not only would the informant have been grieving, but he or she would have only second-hand knowledge of facts such as the deceased’s date and place of birth or his parents’ names. Research other sources to confirm the data a death record provides on a person’s life. Nonetheless, particularly from more recent years, a death certificate can deliver a wealth of information about a deceased ancestor and jump-start your search for earlier details about his life. Among the facts you might find in a death record are: Deceased’s name Age at death Cause of death and details about the length of illness, along with name of attending physician Exact time of death Witnesses at the time of death Name and location of mortuary Date and/or place of burial or disposition of cremated remains Maiden name of a deceased woman Marital status at the time of death Name of surviving spouse Date and/or place of birth Names of parents and sometimes their place of birth Name and sometimes address of informant Residence of the deceased Occupation and/or name of employer Religious affiliation How long in this country or location Social Security number (common on records after 1950) The names you find in a death record can of course lead you to other relatives, and perhaps even push back your genealogical search by a generation (pending confirmation from primary sources). The name of the informant could also be exactly the clue you need to solve a maiden-name mystery. Place names, however, can provide equally important clues: An ancestor’s burial location can lead you to the cemetery, where previously unknown relatives may be in nearby graves. A residential address can aid your search in census records, city directories or land records. Besides filling in blanks in your family tree, dates can point to other records—newspaper obituaries, passenger records, other vital records. Even the cause of death can be helpful, whether in building a medical family history or (in cases of accidental or criminal causes) prompting a search for newspaper articles about the fatality. Death record coverage Today we think of every death as being carefully scrutinized and recorded. Even if a deceased person doesn’t undergo the sort of medical examination common on TV shows such as “CSI:” or “Bones,” at least a funeral home is involved <familytreemagazine.com> Individual towns or counties may and a sheaf of paperwork generated. People in 21st-century America who leave this world are just as well-documented as when they arrive in it or get married. Unfortunately for genealogists, however, such meticulous recording hasn’t always been the case. Depending on where and when your ancestor died, death records may be skimpy or even nonexistent. It’s surprising in our data-dependent era to learn that some states didn’t require recording of deaths until the first decade or so of the 20th century. The earliest state to start death registration is Massachusetts, in 1841, followed by New Jersey in 1848. Recording in Southern and the newer Western states was generally later, with official death records beginning in Louisiana, Tennessee and Arkansas only in 1914, and South Carolina in 1915. Illinois was the last Midwestern state, in 1916. West Virginia followed in 1917; New Mexico and Georgia were last to start recording deaths, in 1919. Even after statewide death registration began in a state, compliance from border to border may have taken another few years, and you may find gaps in the records. But individual towns or counties may have started records much earlier than the states. In Virginia, for example, which waited on statewide records until 1912, some counties kept death FAST FACTS: DEATH RECORDS EARLIEST STATEWIDE REGISTRATION: Massachusetts, 1841 LAST STATEWIDE REGISTRATION: New Mexico and LOCATION OF OFFICIAL RECORDS: County courthouse, Georgia, in 1919 state archives or libraries, state vital-records offices PRIMARY SOURCE DETAILS: date, place and time of death, other death-related information SECONDARY SOURCE DETAILS: facts about an ancestor’s life,such as birth date and place, and parents’ names WEB SEARCH TERMS: death certificates genealogy, vital records genealogy FIND IN THE FAMILYSEARCH CATALOG: Search for the place name (typically by state), then scroll to Vital Records Indexes and/or Vital Records. Click to view listings of death records and indexes available on microfilm, in print and online at FamilySearch.org. ALTERNATE AND SUBSTITUTE RECORDS: funeral home records, obituaries, death notices, cemetery records, Social Security Death Index, military death and pension records, census mortality schedules, burial permits or body transit permits, coroner’s records have started recording deaths much earlier than the states did. records (including for slaves) as early as 1853. Louisiana, although among the last to adopt statewide registration, has some county death records as far back as 1803. Many New England towns started keeping death records in their earliest days, dating to the 17th century. In other places, major cities may have begun death registration well before the rest of the state: St. Louis recorded some deaths, for instance, from 1850 to 1910, and Charleston began in 1821, nearly a century before South Carolina mandated it. The information in early death records, particularly those at the town or county level before statewide registration, may vary widely from place to place. Although privacy restrictions more commonly affect the availability of birth records, you may run into some such roadblocks with death certificates, too. Unless you’re an immediate relative, death certificates are private for 20 years in Maryland, 25 years in Texas, and 50 years in Arizona, New Mexico, New York, Oregon and Tennessee. In Florida, access is granted but the cause of death will be redacted on certificates less than 50 years old. Three states—Colorado, Iowa and Nevada—completely restrict access, regardless of how long ago the person died, to “qualified applicants.” In Iowa, for example, applicants must have “direct or tangible interest in the record” and prove “a lineal relationship to the registrant, such as a legal parent, grandparent, spouse, brother, sister, child, legal guardian, or legal representative.” Nonrelatives can access Colorado death records by obtaining signed, notarized consent from such a direct relative (whose relationship to the deceased must be proven by a copy of the person’s birth certificate). Accessing death records The original repository for most death records was an office, such as the health department or vital records office, in the county where the death occurred. Depending on the date of the record, you might get a copy there, or hit up another repository. STATE AND COUNTY OFFICES: Generally, you’ll request copies of death records created after statewide death registration began from state vital records offices or health departments. You can find these offices’ websites with a web search (Ohio death certificates or Ohio vital records, for example). Or consult the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s list of links to state vital records offices <www. cdc.gov/nchs/w2w.htm>. Family Tree Magazine AT A GLANCE: DEATH CERTIFICATES 1 2 3 4 1 Take note of the deceased’s marital status as well as spouse’s name; here’s evidence that H.G. Miller died before June 1933. 2 Sometimes death records provide useful clues for further research, such as the name and birthplace of the deceased’s father. 5 3 Sources for finding a mother’s maiden name can be scarce. But now you can follow up searching for Blackfords in Kentucky, and for a marriage record for Katherine and J.M. Collier. 4 An informant’s name can provide clues: This informant’s last name is different from the deceased’s maiden and married names. How is she related—possibly a married daughter? <familytreemagazine.com> 5 The name of the undertaker can help you find funeral-home records that could contain more information. CITATION FOR THIS RECORD: Missouri Death Certificates, 1910-1962, No. 22056, Mary Susan Miller; digital image, Missouri Digital Heritage, Missouri State Archives (http://www.sos.mo.gov/ archives/resources/deathcertificates: accessed 5 June 2011). AT A GLANCE: NEWSPAPER OBITUARIES 1 2 3 4 5 1 Obituaries typically give the deceased’s age and place of birth (which can lead to birth records) and survivors’ names— though the wife and children aren’t named here. 2 Details of Mr. Brownlee’s death on the Gettysburg battlefield are clues to discovering records of his military service. Keep in mind tales of heroism may have been embellished. 3 Shorter death notices offer basic facts about the date, place and cause of death. These name the survivors, candidates for further research. 4 Vital recordkeeping gaps during the Civil War in many places mean newspapers may be the only source for death information. 5 Newspapers are generally considered secondary sources of information, because a reporter’s accounts are based on someone else’s recollection. Try to confirm details in other sources. CITATION FOR THIS RECORD: “Obituary of Wm. M. Brownlee,” The Abingdon Virginian (Abingdon, Va.), 13 Nov. 1863, p. 3, col. 3; digital image, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov: accessed 16 July 2013). Family Tree Magazine TOOLKIT County or city offices covering the place where the death occurred also may provide access to death records, and they may have fewer access restrictions and lower fees. They’ll also likely have any records kept before statewide death records began. Check the department of health website for the locality where the death took place for details. Whether you request from the county or the state, follow the site’s instructions for submitting your order. You may have to print a form to drop in the mail with a check, or submit an online form with a credit card number. Fees generally range from $6 to $15. Usually, you’ll have to provide at least the deceased’s name at death and the date and place of death. If you know the death certificate number, supply that as well. You can order the same records available at state vital records offices through third-party businesses such as VitalChek <www.vitalchek.com> (in some states, this is your only option). Such businesses often provide faster service, but usually for a higher fee. Early death certificates may have been transferred to a state or county archive, library or historical society. The health department or vital records office website should inform you if this is the case, or you can consult local genealogy guides. ONLINE: A handful of states and localities provide online access to digitized death records for at least some span of years. Arizona offers a searchable index covering 1844 to 1962, linked to PDFs of the originals, at <genealogy.az.gov>. Nearly a million Michigan death certificates from 1897 to 1920 are digitized at <seekingmichigan.org> (click Advanced Search). You can find digitized Cincinnati death (and birth) records from 1865 to 1910—predating Ohio statewide vital recordkeeping—on the University of Cincinnati Libraries website <digitalprojects.libraries.uc.edu/Births_and_Deaths>. You might find your ancestor in a death index, compiled by someone who looked through death records and extracted names, death dates and other pertinent details. Use this data to request the actual record. The index may have a link to order the record from the holding agency. If not, examine the site for information on the source of the records and directions for ordering a copy or finding it on microfilm. The Massachusetts state archives, for example, indexes deaths from 1841 to 1910 at <www.sec.state.ma.us/ arc/arcsrch/VitalRecordsSearchContents.html> and tells you how to request records. Death records or indexes are increasingly available online at FamilySearch.org. Go to <www.familysearch.org/search> , then scroll down and click United States. Click the state on the left. Look for a death records title on the list in the center of the screen. Some of the collections are still being added to, and not all are indexed. The Social Security Death Index (SSDI), also on FamilySearch.org, is a quick way to find the death date and place of ancestors recent enough to have Social Security numbers. Most of the deaths listed occur after 1962, the year the database was computerized. Websites AmericanAncestors.org <www.americanancestors.org> Ancestry.com: Birth, Marriage and Death <search.ancestry.com/search/category.aspx?cat=34> Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Where to Write for Vital Records <www.cdc.gov/nchs/w2w.htm> Cyndi’s List: Death Records <cyndislist.com/death> FamilySearch.org <www.familysearch.org/search> GenealogyBank <www.genealogybank.com> Glossary of Archaic Medical Terms, Diseases and Causes of Death <www.antiquusmorbus.com> Newspapers.com <www.newspapers.com> Online Searchable Death Indexes and Records <www.deathindexes.com> US Census Bureau: Mortality Schedules <census.gov/history/www/genealogy/ other_resources/mortality_schedules.html> The USGenWeb Project <usgenweb.org> VitalChek <www.vitalchek.com> World Vital Records <www.worldvitalrecords.com> Publications and Resources The American Blue Book of Funeral Directors (Kates-Boylston) Birth, Marriage and Death Records: A Guide for Family Historians by David Annal and Audrey Collins (Pen and Sword) Cemetery Research on the Internet by Nancy Hendrickson (Green Pony Press) The Family Tree Sourcebook: The Essential Guide to American County and Town Sources by the editors of Family Tree Magazine (Family Tree Books) The History of Death: Burial Customs and Funeral Rites, from the Ancient World to Modern Times by Michael Kerrigan (Lyons Press) My Ancestor Died of Scarlet Fever: Family History, Diseases and Death Certificates by Ruth Alexandra Symes (Portrayer Publishers) Tracing Your Ancestors Through Death Records: A Guide for Family Historians by Celia Heritage (Pen and Sword) Your Guide to Cemetery Research by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Betterway) Put It Into Practice ________________________________________________________ To find these record collections and indexes, run a Google search on the city, county or state, death records and genealogy. Also check websites of the state archives and the state and local genealogical society. Search online for books containing death indexes, too. Most subscription genealogy sites have death records and indexes, most notably World Vital Records <www.worldvital records.com> and Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>. Search these sites’ list of databases by place and then scroll to see whether death records are available. Especially for New England ancestors, the American Ancestors subscription site <www.americanancestors.org> from the New England Historic Genealogical Society may have local death records unavailable elsewhere online. MICROFILM: The Family History Library has microfilmed death records and indexes for locations across the country. Search the online catalog at <www.familysearch.org/catalogsearch> for the place your ancestor may have died, then scroll through the results for death records. You can borrow these through your local FamilySearch Center. State archives and local libraries also may have microfilmed death records you can borrow through interlibrary loan. 2. Where was Henry’s last residence? Death record substitutes 1. Why might it be difficult to find a death certificate for an ancestor who lived in the early 1800s? ________________________________________________________ 2. A death certificate is … a. a primary source for details about the deceased’s death b. a secondary source for information such as birth and parents c. a primary source for information such as birth and parents d. a and b EXERCISE A: Go to FamilySearch.org’s database of Ohio Deaths 1908-1953 <familysearch.org/search/collection/1307272> and search for Henry Essel. View the record for the Bavarian immigrant born in 1844. 1. When did Henry die? ________________________________________________________ 3. What were the names of Henry’s parents? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ 4. Write a citation for this record. ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ EXERCISE B: Pick an ancestor whose obituary you want to find. Using the Chronicling America website <chroniclingamerica.loc. gov>, identify three newspapers from places your ancestor lived to search for an obituary. If your search for official death records fails, or you need to supplement skimpy information in what you’ve found, other resources can help. Of course, there are cemetery and tombstone records, which you can read about in an upcoming Workbook. But don’t overlook funeral home, newspaper, church and even census records: FUNERAL: The information in these records may include names of family members, details of the funeral service and even the cost of burial. You may be able to identify the funeral home from the death certificate, newspaper obituary, cemetery records or family papers. A funeral home that nearby relatives used is a likely bet, or you can check city directories of the time for funeral homes near where the family lived. Then you can try to locate the funeral home today (or its successor), either through a web search or directory websites such as <www.funeralhomes.com>, <www.funeralhomedirectory. com> or <www.us-funerals.com> . A printed directory to US funeral homes, which your library or a cooperative local funeral director may have, is The American Blue Book of Funeral Directors (Kates-Boylston). Historical societies and ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ TIP: If the state where your ancestor died had yet to begin statewide record-keeping by the time of his death, check town, city and county records, which may have begun earlier. MORE ONLINE Free Web Content Vital Records Chart downloadable cheat sheet <familytreemagazine. com/info/recordreferences> Cemetery research kit <familytreemagazine.com/article/ your-cemetery-equipment> Genealogy Q&A: Finding a death date and place <familytreemagazine. com/article/pinpointing-a-deathdate-and-place> For Plus Members ShopFamilyTree.com Finding your ancestor’s burial place US Vital Records on-demand webinar <familytreemagazine.com/article/ buried-treasures> Vital records resources <familytreemagazine.com/article/ the-facts-of-life-vital-records> <shopfamilytree.com/vital-recordsresearch-online-recording> Getting Creative With Death Records video class <shopfamilytree.com/ digw-get-creative-w-death-records> Family Tree Essentials CD <shopfamilytree.com/family-treeessentials-cd> Online vital records guide <familytreemagazine.com/ article/vital-signs> libraries in your ancestor’s hometown also might help you track down funeral homes, especially those that’ve been absorbed by other homes. When contacting a funeral home, remember that it’s a private business. While funeral homes are often helpful to genealogists, they are under no obligation to be. You may be asked to demonstrate your connection to the deceased. NEWSPAPER: The local newspaper may have recorded your ancestor’s passing in the form of a death notice listing just the basic facts, or an obituary with details about his life and family. The proliferation of online digitized newspapers can help you find these. Try Ancestry.com and its sibling site Newspapers.com <www.newspapers.com>, both of which require a subscription; subscription site GenealogyBank <www.genealogybank.com> , which also has a database of recent newspaper obituaries; subscription site Archives.com <www.archives.com>; and the free Chronicling America site from the Library of Congress <chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> . Several states have online newspaper collections, including Colorado <www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org>, Georgia <dlg.galileo.usg.edu>, Washington <www.secstate.wa.gov/history/newspapers.aspx> and others. Ask your library if it subscribes to ProQuest Obituaries, a service that offers more than 10.5 million obituaries from newspapers dating back to 1851. Newspaper Obituaries on the Net <newspaperobituaries.net> is a collection of links to other websites. And the USGenWeb Obituary Project <usgwarchives.net/obits> provides transcriptions of public domain obituary indexes and transcriptions, organized by state and county. In addition, check archives, historical societies and libraries in the area where your ancestor lived for indexes to obituaries and death notices, such as those of Alaska Libraries, Archives and Museums <lam.alaska.gov> and the Wisconsin Historical Society <www.wisconsinhistory.org>. You can also use an online search engine such as Google <google.com> or Bing <bing.com> to look for ancestors’ obituaries. Try searching for a name plus obituary; include a place if the deceased’s name is common. CHURCH RECORDS: Many churches recorded the deaths of their members in funeral registers. Your research strategy for these records varies by the religion. Your best bet PUT IT INTO PRACTICE ANSWERS 1 Most states and counties didn’t keep death certificates in the early 19th century. You would need to look for other types of death records. 2d. 3c. EXERCISE A 1 Dec. 14, 1945 2 140 Mason St., Cincinnati 3 Henry A. Essel, Elise Bauer 4 “Ohio, Deaths, 1908-1953,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/ X6YP-CYT: accessed 24 June 2013), Henry G Essel, 14 Dec. 1945. is to contact the place of worship your ancestor attended. If it no longer exists, contact the parish that absorbed it or a regional office for the faith. You also might find church records microfilmed through the Family History Library: Run a place search of the FamilySearch online catalog and look for a church records heading. CORONER RECORDS: Deaths occurring by accident or under suspicious circumstances may have been subject to a coroner’s investigation. The death certificate and newspaper articles may indicate such a death. Coroner records may be at the county morgue, historical society or state archives. Old coroner records are online, at least in index form, for a few areas, such as San Francisco <www.sfgenealogy.com/sf/ sfdata.htm#sfcoroner>, St. Louis <www.sos.mo.gov/archives/ resources/coroners> and Summit County, Ohio <www. familysearch.org/search/collection/1985540>. Look for these on FamilySearch microfilm, too. CENSUS MORTALITY SCHEDULES: US census mortality schedules for 1850, 1860, 1870 and 1880 name those who died in the 12 months prior to the census date (June 1) for these censuses. Find mortality schedules on Ancestry.com. The 1850 schedule is searchable free on FamilySearch.org. MILITARY RECORDS: For ancestors who died in military service, search the Nationwide Grave Locator <gravelocator. cem.va.gov>, which lists burials in Veterans Administration National Cemeteries, state veterans cemeteries, other military and Department of Interior cemeteries, and veterans buried in private cemeteries with government grave markers furnished after 1997. Also peruse military records and pensions on the subscription site Fold3 <www.fold3.com>. One way or another, your ancestor’s final chapter is out there for you to read. And what you find out about his death may open a whole new window in learning about his life. <familytreemagazine.com> DEATH RECORD WORKSHEET Name of ancestor at death Other names used (including a maiden name) Variant spellings Date of death (give approximate date if exact date isn’t known) Place of death (if known) Place of burial (if known) Statewide death registration start City/county death registration dates Contact to request official record, if extant Online databases to search Microfilm to order Newspapers to check for obituary/death notice DEATH RECORD EXTRACTION FORM Source citation: Repository of original: Date accessed: Death record file number: Deceased’s name: Sex: Name of father: Place of death: Race: Birthplace of father: Date of death: Marital status: Name of mother: Cause of death: Name of spouse: Birthplace of mother: Was there an autopsy? Date of birth: Informant: Name of attending physician: Place of birth: Address: Place of burial: Age at death: Date of burial: Occupation: Funeral home or undertaker, name and address: Residence: Relationship to the deceased, if given: Date certificate filed: Family Tree Magazine ECORDS FROM HOME, ACROSS THE PON AND BEYOND Explore our collections from across the United States Over 1 billion records from overseas, dating from 1200 British Newspaper Archives: 300 years of regional and to the present national newspapers from England, Wales, Scotland Over 46 million parish baptisms, marriages and burials and Ireland from across England and Wales dating back to 1538 Rare and unrivaled Irish specialist records search with the experts

© Copyright 2026