C

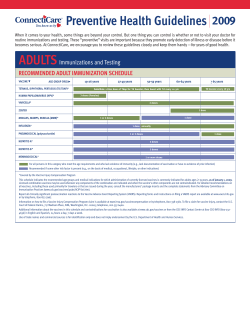

Use of Cancer-Screening Services Among Persons With Serious Mental Illness in Sacramento County Glen L. Xiong, M.D. Richard A. Bermudes, M.D. Serina N. Torres, B.A. Robert E. Hales, M.D., M.B.A. Objective: This study examined the use of breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancer– screening services by persons with serious mental illness enrolled in the Sacramento County Mental Health clinics. Methods: Of 387 outpatients approached from January 2005 to May 2007, 229 were interviewed. Results: Whereas 97% of the women had received cervical cancer screening at least once in their lifetime, more than 50% of eligible persons over age 50 had never received colorectal cancer screening. Recent use of screening services was highest for cervical cancer (69% had had a Pap test in the past three years) and lowest for colorectal cancer (12% had had a fecal occult blood stool test in the past year or a flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy in the past five years). Conclusions: Among persons with serious mental illness, lifetime screening of cervical cancer was higher than for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers. Receipt of routine, timely cancer screening was low, especially for colorectal cancer. (Psychiatric Services 59:929–932, 2008) The authors are affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis, 2230 Stockton Blvd., Sacramento, CA 95817 (e-mail: [email protected]). PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES C ompared with the general population, persons with serious mental illness tend to have significantly more medical comorbidities and higher mortality rates (1,2). Whether this population also shows higher overall cancer prevalence and mortality remains an epidemiological debate (3). However, use of and access to preventive and general medical care among persons with serious mental illness is a major concern for consumers, providers, and policy makers. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, American Cancer Society, and other medical organizations have guidelines on screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancers (4). Cancer screening and public policies to promote such programs have resulted in decreased cancer mortality in the general population, especially for breast and cervical cancers (5,6). However, very little information is available about use of cancer-screening services by persons with mental illness. A few studies have suggested that women with serious mental illness have lower use of preventive breast and cervical cancer screening than do women without serious mental illness (7,8). There is very little information in the literature about the use of prostate and colorectal cancer screening in this population. This study examined utilization patterns of cancer-screening services among consumers enrolled in public-sector mental health clinics in Sacramento County. Such information may be used to monitor health ♦ ps.psychiatryonline.org ♦ August 2008 Vol. 59 No. 8 care utilization by persons with serious mental illness and to guide public policy (9). Methods The Sacramento County Health and Human Services (SCHHS) Division of Mental Health Services contracts its outpatient mental health services with four independent mental health clinics. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, Davis, and the SCHHS Research Committee. Administrators from all four mental health clinics agreed to participate in the study, and they also provided office space for the interviews to take place. Participants were approached before their visits with their providers or before group activities. Interviewing took place before or after the visits. Participants were informed that they would be asked a series of questions about their use of preventive health services. Participation was voluntary, without any compensation and independent of routine care. Adult patients (age 18 and up) with mental illness were sequentially approached and surveyed. The interviews lasted ten to 20 minutes. Participants were interviewed about demographic characteristics, health status, and use of preventive health services. The most recent multiaxial diagnostic information, based on the DSM-IV-TR, was extracted from written charts. A total of 387 participants were approached from January 20, 2005, to 929 Table 1 Self-reported use of cancer-screening services by 229 persons with serious mental illness Time of screen N Mammogram (N=111)a Never <1 year ≥1 but ≤2 years >2 but ≤5 years >5 years Unsure or no response Clinical breast exam (N=111)a Never <1 year ≥1 but ≤2 years >2 but ≤5 years >5 years Unsure or no response Pap test (N=121) Never ≤3 years >3 years Unsure or no response Prostate specific antigen test (N=62)b Never ≤1 year >1 year Digital rectal exam (N=64)b Never ≤1 year ≥1 but ≤2 years >2 but ≤5 years >5 years Unsure or no response Fecal occult blood test (N=68)c Never <1 year ≥1 but ≤2 years >2 but ≤5 years >5 years Unsure or no response Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy (N=68)c Never ≤5 years >5 years Unsure or no response Any colorectal cancer screen (N=68)c Never Fecal occult blood test ≤1 year, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy ≤5 years, or both Fecal occult blood test >1 year, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy >5 years, or both Unsure or no response a b c % 95% CI 30 33 16 18 13 1 27 30 14 16 12 1 11%–43% 14%–45% 0%–32% 0%–33% 0%–29% 0%–19% 3 47 19 16 22 4 3 42 17 14 20 4 0%–21% 29%–58% 1%–35% 0%–32% 4%–37% 0%–22% 2 83 34 2 2 69 28 2 0%–19% 59%–79% 13%–43% 0%–19% 46 8 8 74 13 13 62%–87% 0%–36% 0%–36% 27 7 5 7 16 2 42 11 8 11 25 3 24%–61% 0%–48% 0%–43% 0%–48% 19%–68% 0%–37% 47 3 3 5 7 3 69 4 4 7 10 4 56%–82% 0%–54% 0%–54% 0%–61% 0%–68% 0%–54% 52 9 2 5 76 13 3 7 65%–88% 24%–89% 0%–58% 0%–72% 38 56 40%–72% 8 12 0%–34% 17 5 25 7 4%–46% 0%–30% After age 29 After age 39 After age 49 May 30, 2007. From this sample, 153 participants declined to participate and five participants provided incomplete data that were not analyzable, yielding a total of 229 completed surveys for final analysis. For each question, answers were considered valid if 930 participants answered “unsure” or “unknown,” and answers were not scored if the question was left blank. Study variables included age, gender, ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, Hispanic or Latino, American Indian or Alaska Native, mixed ancesPSYCHIATRIC SERVICES try, and other), marital status, education level (<12 years, high school or GED, some college, and college graduate), income (grouped into <$10,000, $10,000–$15,000, and >$15,000). All questions had an additional response of “don’t know/unsure” to provide participants the option to not answer questions. Women were asked about their use of mammogram services, clinical breast exam, and the Papanicolaou (Pap) test. Men older than 39 were asked about their use of the prostatespecific antigen (PSA) test and digital rectal exam for prostate cancer. All participants older than 49 were asked about colorectal cancer screening via fecal occult blood stool test (FOBT) and flexible sigmoidoscopy (flexsig) or colonoscopy. For each cancerscreening service, participants were asked about lifetime history of screening (responses were yes, no, and unsure). If an affirmative answer was given, an additional question was asked about whether the screening had occurred in time intervals of less than one year, between one and two years, between two and three years, between three and five years, more than five years, or unsure or declined to answer. For data analysis, descriptive statistics were reported as mean and standard deviation for age and percentages with 95% confidence intervals calculated for each categorical variable. Data for year intervals were combined when relevant to facilitate presentation of the results. Results The participants’ mean±SD age was 40.15±10.10 years. There were 106 men (46%) and 123 women (54%). Only 23 participants (10%) were married, and 184 participants (80%) were enrolled in a government-sponsored health care insurance program. Of the 229 respondents, 55 (24%) did not complete high school, 78 (34%) completed high school or earned a GED, and 95 (42%) had education beyond high school. Primary diagnoses included 79 persons with schizophrenia (35%), 92 with bipolar disorder (40%), and 50 with recurrent major depressive disorder (22%). The use of cancer-screening services is summarized in Table 1. Most ♦ ps.psychiatryonline.org ♦ August 2008 Vol. 59 No. 8 women had received clinical breast examination and cervical cancer screening at least once in their lifetime. Among men older than 50 years (data not shown in table), 21 of 32 (66%) had never received PSA testing for prostate cancer. However, only eight of 32 (25%) participants older than age 50 had never received a digital rectal exam. Among eligible men and women (over age 50), 38 out of 68 (56%) had never received screening for colorectal cancer. The pattern for up-to-date cancer screening (Table 1) was similar, with more women having had a Pap test in the past three years (83 of 121, or 69%) than had a mammogram in the past year (30 of 111, or 30%), or for men a PSA test in the past year (eight of 62, or 13%), or for all participants an FOBT in the past year or a flexsig or colonoscopy in the past five years (eight of 68, or 12%). Discussion This study examined the utilization patterns of cancer-screening services among persons with serious mental illness who were attending public mental health clinics. This survey found that the proportion of people who had never had breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer screening was much higher compared with cervical cancer screening. This finding may be secondary to easier access to and earlier temporal indication of routine screening for cervical cancer compared with the other cancers. For example, the Pap test is more readily available via community programs (such as Planned Parenthood), and cervical cancer screening is offered much earlier (within three years of onset of sexual activity or at age 21). Persons with serious mental illness consistently received little up-to-date screening of the four cancers considered in this study. This finding indicates that even among those who have received cancer screening in the past, persons with serious mental illness did not get cancer screening on a routine basis. Recent colorectal cancer screening occurred least often. The mechanisms behind these differences require further research, and up-to-date cancer screening may be a potential target for intervention. Reasons for not getting routine PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES screening services among those who received cancer screening in the past are likely to be different compared with those who have never received any cancer-screening services in their lifetime. This is an important area that would require further research from different vantage points— among consumers, providers, and health care administrators. The use of preventive health services by persons with serious mental illness has been studied scantily in different settings, although methodologies have varied. Very few studies have been based on interviews of persons with serious mental illness in ambulatory settings. Most studies have relied on chart review, physician surveys, or insurance claims (10–12). Of 43 participants ages 40–70 years, Dickerson and colleagues (13) found that eight (19%) had never received a mammogram and 26 (61%) had received a mammogram in the past two years (13). We report slightly lower receipt of mammogram services, although our age cutoff was lower. Of 81 respondents who had received a mammogram in their lifetime, only 49 of 111 women asked (44%) had received one in the past two years. In another outpatient sample, Carney and colleagues (14) found that 119 (90%) of 133 participants received at least one Pap test. We found a similarly high rate of lifetime cervical cancer screening of 97%. Therefore, despite temporal and methodological differences, our findings are largely consistent with previous studies of breast and cervical cancer screenings. This study is the largest available study based on personal surveys of the use of cancer-screening services in community mental health programs that we are aware of. We also collected comparison data on use of four cancer-screening services by persons with serious mental illness. There are several methodological limitations. First, we did not have information about participants who declined to participate in the survey. It is possible that their use of preventive health services is even lower. Second, because we relied on patient recall about receipt of the services, recall bias may have decreased the accuracy about actual receipt of services. This ♦ ps.psychiatryonline.org ♦ August 2008 Vol. 59 No. 8 limitation could be addressed by randomly validating the responses with the participants’ medical records in future studies. Third, we did not characterize the settings where the preventive services were provided (for example, by mental health providers or primary care providers). Finally, we did not directly compare persons with serious mental illness with persons without serious mental illness; rather, the survey clinical sample provided descriptive information about persons enrolled in public mental health clinics. Utilization of cancer-screening services depends on many factors, including health attitude, perceived discrimination, general disability, number and severity of medical comorbidities, access to medical services, and recommendations from physicians (15). The results from this study are not necessarily generalizable to other mental health systems. However, our study highlights the importance and feasibility of personal health surveys in monitoring the receipt of cancer-screening services by enrollees of the public mental health system. Conclusions This study examined the use of preventive cancer-screening services by persons with serious mental illness. The continued monitoring of the use of cancer-screening services can be informative as part of a general health system performance measure and can guide future resource allocation of health promotion programs. Acknowledgments and disclosures This study was supported in part by a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression young investigator award to Dr. Bermudes. Dr. Bermudes was a speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb in 2007. The other authors report no competing interests. References 1. Barreira P: Reduced life expectancy and serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50: 995–996, 1999 2. Prior P, Hassal C, Cross K: Causes of death associated with psychiatric illness. Journal of Public Health Medicine 18:381–389, 1996 3. Grinshpoon A, Barchana M, Ponizovsky A, 931 et al: Cancer in schizophrenia: is the risk higher or lower? Schizophrenia Research 73:333–341, 2005 disorders in primary care have lower mammography rates? General Hospital Psychiatry 25:214–216, 1993 4. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ: Cancer screening in the United States, 2007: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. Cancer Journal for Clinicians 57:90–104, 2007 8. Carney CP, Jones LE: The influence of type and severity of mental illness on receipt of screening mammography. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21:1097–1104, 2006 5. Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al: Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer 101:3–27, 2004 6. Armstrong K, Moye E, Williams S, et al: Screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine 146:516–526, 2007 7. Lasser KE, Zeytinoglu H, Miller E, et al: Do women who screen positive for mental 9. Luck J, Chang C, Brown ER, et al: Using local health information to promote public health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 25:979– 991, 2006 Services 55:1250–1257, 2004 12. Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, et al: Receipt of preventive medical services at psychiatric visits by patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:884– 887, 2002 13. Dickerson FB, Pater A, Origoni AE: Health behaviors and health status of older women with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 53:882–884, 2002 10. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Medical Care 40:129–136, 2002 14. Carney CP, Allen J, Doebbeling BN: Receipt of clinical preventive medical services among psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services 53:1028–1030, 2002 11. Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, et al: Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric 15. Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ: Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21:553–558, 2006 Coming in September ♦ Psychiatric disorders among youths referred to adult criminal court ♦ Improving treatment for co-occurring disorders: three research reports ♦ Architectural paternalism: ethics in the past and current design of psychiatric hospitals ♦ Focus on homelessness and housing: three new studies 932 PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES ♦ ps.psychiatryonline.org ♦ August 2008 Vol. 59 No. 8

© Copyright 2026