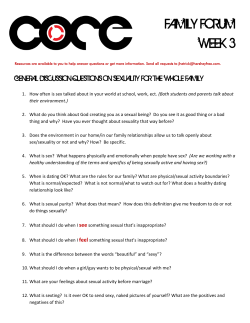

VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN AFRICA