He was Hollywood’s golden boy. Then, after some

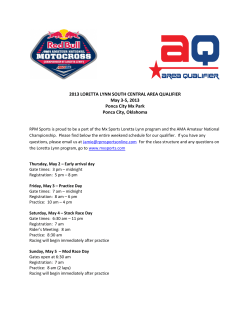

He was Hollywood’s golden boy. Then, after some big-screen flops, Kevin Costner’s star faded. But now, he reveals, he yearns to be famous for something other than movies. By Ariel Leve. Portraits by Barry J Holmes FIELD OF UNFULFILLED DREAMS On a crisp and sunny December afternoon in Los Angeles, the electronic gates to Casa di Pace – the “house of peace” – are opening up.A labrador called Wyatt appears, tail wagging.The drive culminates in a hacienda that is tucked away deep in the Hollywood Hills. Inside, two comfy armchairs frame a blazing log fire and Kevin Costner is seated in one of them.“C’mon in!” he calls out, smiling warmly as he holds out his hand. “Hi,” he says.“I’m Kevin.” He is tall, wears a T-shirt and worn blue jeans, and his 49 years only show in the creases around the eyes. He is naturally, ruggedly handsome without being groomed, and confident without being smug. Costner loves his kids, his dogs, and baseball. It soon becomes apparent he likes women too. His company is comfortably masculine, like the dad the baby-sitter wants to sleep with. He is disarmingly unafraid to show the gaps in his 46 education. He doesn’t try to be a deep thinker, he 46 The Sunday Times Magazine 22 feb 2004 doesn’t pretend he’s the smartest guy in the room. He cuts a figure of the ordinary guy who could be a hero, a strong yet vulnerable and sensitive man, the type he likes to play in his movies, over and over. But is it the man he is or wants to be? Or is Kevin Costner looking for a new role? This afternoon, where’s the surly bore, the vaulting ego, the tabloid image of the arrogant womaniser? He sits, one leg crossed over the other, his foot bobbing in the air with anticipation. He undoubtedly has sex appeal: millions of women know it and, like the characters he often portrays, it is judicious and anchored with a conventional decency. Perhaps it is because he is relaxed and we are on his home turf. It’s unusual, since stars are supposed to protect their privacy with lawyers and guard dogs, but also intentional because it is clear that his home is his sanctuary. He feels safe here.“I can have you in my home and still have my a 22 feb 2004 The Sunday Times Magazine 47 PREVIOUS PAGES: GROOMING BY JENNIFER PITT @ ARTISTS. THIS PAGE, LEFT: REX. RIGHT: AP privacy,” he explains.“In fact, I think our privacy is really well preserved – we’re not having someone come over and interrupt us.” It also puts him in control – and control, as we shall see, is central to Costner’s existence. In September, Costner is getting married to Christine Baumgartner, 29, a bag designer, at his ranch in Colorado.They have dated for four years, and this will be his second marriage after a very public and messy divorce in 1994.Why would he want to make the commitment again with the pain of divorce still apparent? Costner isn’t sure. He looks puzzled. Not uncomfortable, exactly, but mentally making a readjustment.“Ohhh,” he says, narrowing his eyes, “you’re one of those...Well, it’s probably not as important to me to be married but it’s important to her.The truth is, I never want to be divorced again.That’s the scary part of committing – but in some way you’re saying,‘My level of commitment to you is not vague and it’s not foggy and I don’t necessarily need that title, but if you do, you’re my partner and we’ll do that.’And you just can’t be paralysed. I have a good look at the world. I see what the world is. I see what the possibilities are – I see what the realities are – you can wake up tomorrow and feel differently.That’s possible.The one thing for sure is, if you don’t commit to anything, you’re not going to feel the loss.” Costner’s view of himself as a man with passionate determination has often been complicated by his reputation as someone who wilfully and stubbornly wants his own way. Rather than concede, he’ll go it alone, creating an image of an enigmatic loner, a perception that he acknowledges but disputes. He tells a story: when he was in college, he suggested to some of his friends that they go up to Alaska and work on fishing boats and make money, but he couldn’t get anyone to go with him. He still went, by himself. He uses this story to illustrate that he prefers to be with people but is equally comfortable to strike out on his own. It is an anecdote that reinforces his reputation as an isolated and remote individual and his independent self-image. He’ll make the movie he wants to make and is not easily dissuaded.This quality has defined Costner. It’s anointed him as a visionary film-maker (Dances with Wolves) and underlined his fall from grace (The Postman). There are moments in people’s lives where everything culminates and glory is achieved. For Costner, this was Dances with Wolves. He had box-office success as an actor, yet nobody suspected he had more to offer. But all along, he’d been observing. On the set of The Big Chill, even though his part was cut, he befriended Lawrence Kasdan, the director, and he absorbed and he waited.And when the opportunity came, he was ready to say something with Dances with Wolves. He had never directed before.And the plight of the American Indians was not considered blockbuster material by mainstream Hollywood. His tireless persistence in getting the film made was extraordinary. It put Native Americans in the consciousness of a global audience, and whether Above: Costner with his first wife, Cindy Silva, in 1993. The couple divorced a year later. Right: at this year’s Golden Globe awards with his daughter Lily, 17, (far right) and his fiancée, Christine Baumgartner, whom he will marry in September he was brave or lucky, driven by ego or vision, he showed courage in keeping at it. He ignored negative reactions from studio executives who didn’t believe he could pull it off.And he refused to cut out the Sioux subtitles.Against the odds, he made a film that mattered. For a long time, Costner could do no wrong. He was handed miles of rope after Dances with Wolves, and he grabbed it. He made Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves,The Bodyguard, and JFK. But his movies since Waterworld raise the question: has his single-mindedness become a millstone? It’s a long time since he’s enjoyed big commercial success. In 1991, Robin Hood took $165.5m at the US box office; his past four films put together didn’t make this amount. Even Waterworld (1995), which was critically panned, took $88.2m in the US and £8m in the UK. Compare that with his 2001 offering, 3,000 Miles to Graceland, which took a paltry $15.7m in the US and went straight to video here. He sticks to his principles yet his instincts seem out of sync with the box office. If the movie landscape has changed, maybe his film-making requires greater risks. Or does he have a fear of change? Costner’s eyes widen and he inches forward in his chair, placing his palms on his knees and looking right at me. He evades the question and, smiling, bats it back.“Do you have that?’ He tells an anecdote about Dances with ‘I NEVER WANT TO BE DIVORCED AGAIN. IT’S THE SCARY PART OF COMMITTING’ Wolves: he read Michael Blake’s manuscript and encouraged his friend to turn it into a screenplay, then decided he would direct it, and then later it was published as a book. If it weren’t for his encouragement and insistence, he says, perhaps the book might never have been published. He’s genuinely proud that he motivated his friend, enjoys taking credit for it.The reluctant hero has a need to be seen as a benevolent guru too. Costner doesn’t consider himself a writer but has no compunction about telling writers what he thinks should be on the page.The same with orchestrations for his movies: even though he doesn’t play music, he will tell the musicians what he wants because he believes he is right.This is one of his most trenchant qualities: he can’t let go. It’s hard to know when Costner speaks his mind whether it is an oversized ego talking or merely a perfectionist’s purpose.This tenacity has been interpreted as egotism, or overzealous selfadmiration, even. So can he admit to failure? “Oh yeah – I’ve failed. But that’s a weird word – I’ve never failed to try.” He pauses, rethinking his answer.“Failed? I’ve had pictures that haven’t succeeded, but I’ve stayed with them. I started an environmental company 10 years ago and it hasn’t succeeded – but it’s going to. I don’t give up on stuff. If I read something and I think it is good, six people won’t convince me it’s not good.” He traces his strength of conviction back to a seminal moment in college (he studied marketing at California State University) when, egged on by peer pressure, he took part in a stupid fraternity stunt.“I came away from it thinking,‘I’ll never be intimidated again.’ It was a dumb thing – it was wanting to belong and thinking that I would do anything to belong, and then catching myself and thinking,‘I won’t ever do that again.’”That Costner reproached himself for nothing a 49 22 feb 2004 The Sunday Times Magazine 49 THE RISE AND FALL OF COSTNER’S STAR With Dances with Wolves and Robin Hood, Costner was on a career high. But after Waterworld came the box-office decline... DANCES WITH WOLVES ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES, 1991 DANCES WITH WOLVES, 1990 $203.7m $202.7m ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES THE BODYGUARD, 1992 $152.9m THE BODYGUARD THE UNTOUCHABLES WATERWORLD, 1995 $103.6m TIN CUP, 1996 $56.3m THE UNTOUCHABLES, 1987 $81.1m THIRTEEN DAYS, 2000 $37m MAIN PHOTOGRAPH: AP. INSET, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: PICTUREDESK.COM, WARNER BROS, REX, PICTUREDESK.COM, MOVIESTORE COLLECTION JFK, 1991 MESSAGE IN A BOTTLE, 1999 $83.3m Figures shown are combined US and UK box-office takings. Source: ACNielsen EDI WATERWORLD A PERFECT WORLD, 1993 $20.7m more than an adolescent desire to belong is intriguing.What young man doesn’t wish to join or conform to something perceived as attractive or desirable? And how can a run-of-the-mill rite of passage for a young student be remembered as such a threat 30 years later? Costner seems almost shocked when told there is a perception of him as guarded, which would seem to be sustained by this anecdote.“That’s ridiculous! It’s not my job to be mysterious.” Despite his resolute stance, he sounds unsure of himself. So the fame doesn’t matter? He insists he is grateful but has regrets.“It’s closed as many doors as it’s opened,” he says. Costner grew up in suburban Los Angeles – his father worked for a utilities company and it was a normal, unturbulent childhood. He was an athlete in high school, went fishing with his father and older brother, Dan, and acted in a couple of amateur musical-theatre productions.There wasn’t much money and he wasn’t a quarterback or a hit with the girls.At university he met Cindy $57m WYATT EARP, 1994 $26.6m THE POSTMAN, 1997 $18.2m Silva, who was working her way through college as Snow White at Disneyland.When asked if he was Prince Charming, he laughs.“No, I was Dopey.” He and Cindy married early, in 1978. He had a series of jobs – truck driver, carpenter, deck hand and, in 1979, stage manager.“My first job was working at a little studio for $28 a day. I was really glad to have that. I didn’t tell people I was an actor. Not because I was ashamed, but because there was work to be done.And no one wants to work next to a pining actor.” By 1985 his acting career was beginning to take off. He was in successful movies such as American Flyers, No Way Out,The Untouchables, Bull Durham, and Field of Dreams.Then, all of a sudden, his own project, Dances with Wolves. He’s winning Academy Awards, is on the covers of magazines, making piles of money. George Bush is calling to play golf. Men want to be him, women want to sleep with him. In the space of 20 months he becomes a superstar, the new Gary Cooper. He is rubbing his chin, pondering an assessment FOR THE LOVE OF THE GAME, 1999 $35.3m 3,000 MILES TO GRACELAND, 2001 $15.7m DRAGONFLY, 2002 $30m that his success came early.“I didn’t have success until 28,” he says, and when it’s mentioned that 28 is quite young, he puts it in a more conventional context. His friends were buying homes, earning a living and opting for security. So what Costner wants us to see is that he took a chance – gambled with his fate and the fate of his family – and, against the odds, it paid off. Costner wants us to see a strong, determined and down-to-earth fellow who has achieved much against the odds, yet is unchanged by his success. But there remains a suspicion of a black hole in his life, as if he isn’t fully convinced that he fulfils the role he clings to. So what’s missing? “What I really hope is that I have the wisdom and the courage to alter my life because I want to alter it, and that I’m not stuck doing movies as the only identity I have.That if I want to stop making movies one day, that I just stop doing it because some other window has opened up for me. I hope I have that kind of courage.That my life can be about other things.” His answer suggests that his fame, his family, a 51 22 feb 2004 The Sunday Times Magazine 51 money and career don’t fulfil him, that there is a large, unidentified void in his life.“I didn’t say anything was missing,” he says, a tad too impatiently.“I said that I don’t think of anything missing. But potentially what could be missing is me not sensing to step in another direction.” And that would be out of fear? There is a long, thoughtful pause.“Well, I don’t think of myself as a fearful person. I’m not looking for a change of career, but if I wanted to just get on a boat and go for two or three years, I have the financial wherewithal to do it – but would I do it? Or do I have to feed my ego by being in a movie?” So is he feeling trapped, or merely anchored by his responsibilities? “I have a daughter in her second year of Brown University and I have one that’s starting to really find herself – and Joe’s now 16... ” He trails off and explains the importance of wanting to be around to raise his children rather than sailing around the world. He thinks of himself as generous – and he is, by most accounts. He likes to be magnanimous, even 52 The Sunday Times Magazine 22 feb 2004 towards his enemies.“If I had a professional looking at me they might say,‘The reason you help that person, that’s about you.’ But in truth, my understanding of it is simply that they said they were sorry, and now they need help again. I’ve done things for people who have hurt me – just because they said they were sorry. I’m kind of a sucker for the word.” He admits to periods of depression when he withdraws and decides he doesn’t ever want to be hurt again. But that means never reaching out, which, he says, is not the way he wants to live. He is still in touch with his emotions; he can be sentimental, things move him.About 10 years ago a friend of Costner’s wrote a song in aid of the families of those involved in the first Gulf war, to be performed by celebrities and singers. Costner got involved.“I was walking to my car and I heard this woman’s voice saying,‘Kevin? Kevin?’ and I was exhausted. I knew there was a distance between her and I, that I could have [pretended] technically not to have heard her but she called one more time, and I stopped, and she said,‘I saw Dances with Wolves, and there’s a scene at the end where you’re holding each other and can’t let go, and my husband is MIA [missing in action].And all I dream about is that moment when I’m going to run to my husband and he’s going to run to me.’ And it just stopped me, and I cut out those two frames of the movie and sent her the pictures.” He says those moments balance out the negatives. Costner on the set of his latest film, Open Range, in which he stars opposite Annette Bening. The film, a homage to the 1953 western Shane, is his third directorial effort after the hugely successful Dances with Wolves and the huge flop The Postman “Nobody made me make these movies. I did them for myself,and when they touch somebody else, it’s just a really cool feeling.When I read a good book or hear a good story, I want to share it.When I hear a good joke, a great band or a good piece of music, my inclination is to share.” I ask him to share a joke.“No,” he says.“It will end up in the article.” Is it a dirty joke? A racist joke? “No.It’s just... weird. I don’t know. I’m guarded about that. Maybe it will just seem silly...” He pauses.“Okay! I’m going to tell you this joke.” He gives it a shot, trying his best to remember it without losing momentum.“A guy knocks over a lamp.A genie appears. He asks if it’s really a genie, and the genie says,‘Yeah, I’m the real thing and I REX HE ADMITS THAT HE’S PLAGUED BY AN INABILITY TO BE MORE SPONTANEOUS can grant you any wish.’ ‘Any wish?’ asks the guy. ‘Yes, any wish.’The guy whips out a map.And he says,‘See this? This is Palestine.And that’s Israel. I want you to fix that. Because it’s been going on too long.’And the genie says,‘I can’t fix that.’ So the guy says,‘Mmm – that’s what I thought.’And he starts to walk away, so the genie says,‘C’mon, gimme another chance.Ask me something else – whatever you want.’ So the guy goes,‘Okay, can you make it so that my wife will like sex with me?’ And the genie looks at him and says,‘Gimme the f***ing map!’” He is laughing now – enjoying himself.Then he sits back, relieved it’s over. Costner’s image has never been regarded as edgy.The most controversy he has courted revolved around affairs with women during, as well as after, his marriage – one of which, after his divorce, resulted in an illegitimate son. He doesn’t hang out with other famous people.There are some he trusts, such as Sean Connery and Andy Garcia.“But I don’t really call them on the phone and they don’t call me.We’re friendly, I find them trustworthy, honourable. My friends are people I went to high school and college with.” It is dusk.The fire is crackling and we have not moved for a couple of hours. Costner, bathed in an orange glow, stands up and stretches.We step outside onto his porch, which overlooks a dark limestone pool covered with leaves. Surveying his property, he explains that he needed a peaceful place to be after his marriage ended. It is chilly, and we step back inside. He resumes his seat. “When I got divorced, there was an enormous light thrown on that. It was very public about my private life.Also,Waterworld, one of the most expensive movies of all time, was being made and, um, a lot of things were not right.And I felt I was being crushed under the weight of it all. But I’d often wondered if I was a strong person – and I surprised myself because I held on.And I didn’t let it crush me. I just held on.” What was the alternative? He responds without hesitation.“That you wilt like a daisy.You bury yourself and go away and think it’s everybody else’s problem. It was a hard time.A hard time.” Despite his Republican leanings, he says he is not dogmatic and is open to having his mind changed, if not his character.“I don’t think it’s a mark of great political cachet for a person who says,‘I’ve never changed. Since 1960. I’m a consistent person.’You go,‘F***, man, I changed yesterday when I heard something really important!’ So I think staunch conservatives are very dangerous. Liberal liberals – really dangerous. “Put it this way: I took my daughter Annie out, she was 15 then – she’s now 19 – and she was beautiful, and we were just walking on the beach and I asked her to look around, and I said,‘Annie? Tell me what you feel.’And she loved me – and felt the love couldn’t get any bigger and she told me so, and I said to her,‘Well, there’s going to be a day that you don’t feel that.You’re going to feel that I’m not the smartest guy in the world.You’re going to feel that I’m holding you back.You’re going to feel a lot of things.And that’s okay. But I want you to know it will be you that’s changed. I haven’t. I’m 42, I’m 44, I’m 49 – this is who I am.You’re going to have a different feeling about me, so all I want you to do is to think back to that time when your love was big and you were 15.’” Suddenly he looks fragile.“There are things about me that won’t change. How I feel about my friends, that’s not going to change. I’m probably – for those who know me – the same as when I was 22. I still get excited about stuff, in a way that I know a lot of my friends don’t.” He admits he’s plagued by an inability to be a 22 feb 2004 The Sunday Times Magazine 53 ‘IF I COULD PICK SOME TROPHY, IT WOULD BE TO BE ON THE COVER OF TIME MAGAZINE AGAIN’ more spontaneous.“I’ve seen others do it and I get kind of jealous – if I’m around people and they’re having a good time,maybe in another country, and they decide they’re going to stay another three days. It doesn’t seem like much, but I’ve never been able to do that in my life. I usually know where I’m going to be on Monday. I’ve been jealous of how others,when they’re having a really good time,they just stay. I’m trying to change that.” Asked if he knows where he’ll be a week from now, he nods.Two weeks from now? He nods.A month? Yes. His life is organised and yet there is something about him that feels strangely displaced.There’s something there, something damaged or broken – but what is it? “It’s not something I want to talk to you about.” Is it the divorce, the separation from his children? Guilt? Or some real or perceived professional betrayal? “I need you to understand why I can’t go into this, because it would affect someone else more than it would affect me.And that’s not fair. But yeah, I’ve been bruised.And the truth is,I don’t think about it all the time – but I know that on a certain level it is probably not over.” His mood has become wistful.Then he says,politely but firmly,“If you don’t mind, I’d rather not talk about it.I’m pretty wide open,” adding, almost apologetically: “It’s just a couple of things.” It is dark.We haven’t talked at all about the movie, Open Range, and when I bring it up, he lets out a deep, torpid sigh.We’ve been talking for nearly four hours.He smiles but looks worn out.“I feel a bit of a headache coming on,” he teases, rubbing his temples.“I’ve had to genuinely think.” He is proud of Open Range (released in the UK on March 19), a western in the mould of Shane – poor, honest folk against land-grabbing predators – and he fought to give the characters depth and integrity.This is evident in a story he tells of a scene between him and Annette Bening that emphasises the subtlety of his character. Others wanted it out, but he insisted it stayed in. His instincts as a storyteller remain uncorrupted by commercial demands. “What time is it?” he asks. Costner does not wear a watch. It is nearly 6pm. His daughter Lily has a basketball tournament and he is concerned he might be missing it. Costner’s children (who have grown up, since his divorce, spending seven days with him, seven days with their mother) are virtually adult. His son is having to adapt to his sisters leaving for college; it’s a vulnerable time for him, and for Costner as well. There is a sadness about him. If he stops acting and directing, what will be next? He pauses.“I was on the cover of Time magazine once. If I could pick some trophy out – and I know I’m saying this all wrong – but it would be great to be on the cover of Time again. But not for a movie. I wouldn’t want to be there for a great comeback.That wouldn’t interest me as much as something else that happened. Because, I guess, I know I would be circling around something that was interesting and vital, and it didn’t have anything to do with the movies. It would mean that I had changed direction in my life – and it was important to me and important to somebody else.” He doesn’t seem cynical or bitter, but while he genuinely likes the movie business, it’s obvious that now, as he’s nearing 50, Costner craves change. It’s something he doesn’t deny:“If I was to have a tombstone, it would be cool if it said at the end, ‘And he made movies too’.” s NEXT WEEK IN THE MONTH Next Sunday we treat you to behindthe-scenes footage, a trailer and an extended clip of Kevin Costner’s new movie, Open Range, on The Sunday Times’ free CD-Rom, The Month. Also: new releases from Norah Jones and Harry Connick Jr February 22, 2004 The Sunday Times Magazine 55

© Copyright 2026