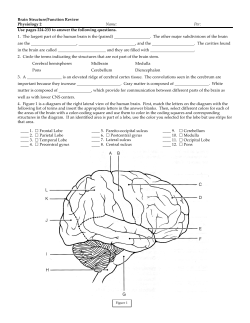

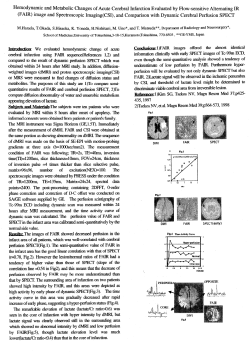

Information about cerebral palsy