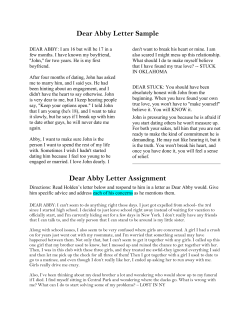

Document 71734