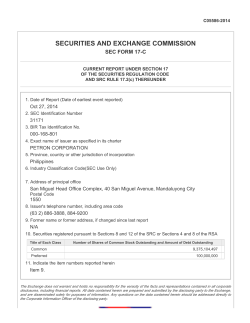

Alert SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance