Document 72338

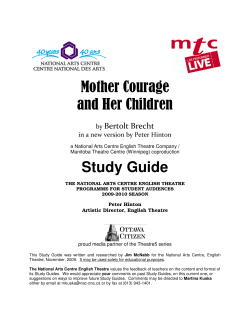

25 Short Street London SE1 8LJ T: 020 7450 1982 E: [email protected] EDUCATION RESOURCE PACK FOR ETT’S 2006 TOURING PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Stephen Unwin TRANSLATION Michael Hofmann SONGS John Willett EDUCATION ASSOCIATE Anthony Biggs SUPPORTED BY THE ERNEST COOK TRUST Poem 2 Cast/creative team and introduction 3 Scene synopsis 4 Director’s notes 9 Demystifying Brecht 13 Translator’s interview 16 Actor’s interview 18 Assistant Director’s rehearsal diary 20 Designer’s interview 23 Costume designer’s interview 25 Discussion points 27 Exercises 27 Chronicle 30 Further reading 32 Views expressed in this pack are not necessarily those of ETT THE STORY OF MOTHER COURAGE There once was a mother Mother Courage they called her In the Thirty years’ war She sold victuals to soldiers. The war did not scare her From making her cut Her three children went with her And so got their bit. Her first son died a hero The second and honest lad A bullet found her daughter Whose heart was too good. Bertolt Brecht (1898 – 1956) 2 MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN THE CAST Mother Courage Kattrin Swiss Cheese Eilif The Cook The Chaplain Yvette Sergeant/Armourer/Ensign Rectruiter/Old Colonel/Farmer General/Clerk Sergeant/Young Man Young Soldier/Farm Boy Old Woman/Farmer’s Wife DIANA QUICK JODIE MCNEE YOUSSEF KERKOUR SAMUEL CLEMENS TOM GEORGESON PATRICK DRURY GINA ISAAC BARRY MCCORMICK MICHAEL CRONIN WALE OJO DANIEL GOODE GORDON TAGGART JANET WHITESIDE All other parts played by members of the company THE CREATIVE TEAM DIRECTOR SET DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUND DESIGNER CASTING DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR ASSISTANT COSTUME DESIGNER PRODUCER Stephen Unwin Paul Wills Mark Bouman Malcolm Rippeth Matthew Scott Dan Steele Ginny Schiller Jamie Harper Mia Flodquist Rachel Tackley This production opened at the Forum Theatre, Malvern on 5th October 2006. INTRODUCTION Welcome to this ETT resource pack which supports our current tour of Mother Courage. For all those students (and some teachers) who are studying Brecht for the first time, and for others that have been sufficiently alienated by talk of his verfremdungeffekt, please be assured that this is not an essay on Brechtian dogma. It is a practical pack, designed to give you both an understanding of Brecht’s writing and his theories, and also the process that we went through to create this production. My guiding reference for writing this pack has been Stephen Unwin, and I have freely plundered from his book: A Guide to the Plays of Bertolt Brecht, which I would urge you to read. The pack also contains interviews with some of our creative team as well as a rehearsal diary and photographs. The questions and discussion points should help you to unlock the heart of this great play, and are designed as much for the rehearsal room as the classroom. This pack is certainly not all encompassing, and I have included a list of further reading at the end for those who want to find out more about this remarkable man and his work. If you have any comments or questions about this pack or indeed the production, please email me at [email protected] I look forward to hearing from you. Anthony Biggs Education Associate 3 SCENE SYNOPSIS This synopsis is based on Brecht’s own notes which he had compiled, along with a model book of photographs taken by his collaborator Ruth Berlau from the 1949 Berlin production. During our rehearsals Stephen Unwin made extensive use of them, as he said: ‘Trying to stage the play without looking at the model book would be like performing Beethoven without heeding the tempi’.The photographs below are of a 1:25 scale model-box constructed by designer Paul Wills. 1. The business woman Anna Fierling, known as Mother Courage, encounters the Lutheran Swedish army. Recruiters are roaming the country looking for young men to join their army. Mother Courage introduces her family to a Sergeant, and tells him that her three children (Eilif, Kattrin and Swiss Cheese) all have different fathers from different war zones around Europe. When she sees that her sons are listening to the recruiters, she predicts that the Sergeant will meet an early death by getting him to draw a piece of paper with a black cross out of his helmet. To make her children afraid of the war, she has them draw black crosses as well. Distracted by small business deal with the Sergeant, she loses her brave son to the army Recruiting Officer. 2. At the fortress of Wallhof, Mother Courage meets her brave son again. Mother Courage sells her goods at exorbitant prices in the Swedish army camp. While driving a hard bargain over a capon (a type of chicken) with an army cook, she overhears the Swedish General bringing a young soldier into his tent and praising him for his bravery. Mother Courage recognises that the young soldier is her lost son, Eilif. The General demands that the Cook provide a good meal for Eilif to reward him for his heroic deeds. Mother Courage takes advantage of the situation and demands a high price for her capon. Eilif does a dance with his sword and his mother answers with a song. Eilif hugs his mother and gets a slap in the face for putting himself in danger with his heroism. Scene 2: Mother Courage can overhear her son inside the tent, boasting to the General 3. Mother Courage switches from the Lutheran to the Catholic camp and loses her honest son Swiss Cheese. Mother Courage sells ammunition to the army on the black market. She serves alcohol to the camp whore, Yvette, and warns her daughter (who cannot speak) not to get involved with men. While Courage flirts with the Cook and the Chaplain, dumb Kattrin tries on the whore’s hat and shoes. A surprise attack from the Catholic army leads to Courage and her family joining the Catholic army camp. Swiss Cheese is arrested because he is a Paymaster in the Lutheran Army. Mother Courage mortgages her cart to Yvette in order to raise money to buy Swiss Cheese’s release. Courage haggles for too long over the amount of the bribe, and hears the volley of bullets that kills Swiss Cheese. For fear of getting in further trouble with the Catholic Army, Courage denies that she knows her son when she is shown his dead body. 4 Scene 3: Mother Courage removes the washing and takes down the flag when the Catholic army attacks 4. The Song of the Great Surrender Mother Courage is sitting outside the Captain’s tent; she has come to put in a complaint about damage to her cart. A clerk advises her not to make a fuss as it may result in more trouble for her. A young soldier appears to make a complaint but Mother Courage dissuades him. She sings the ‘Song of the Great Surrender’. Courage also learns from the lesson she has given the young soldier and leaves without having put in her complaint Scene 4: Outside the Captain’s tent, the damaged cart behind. Courage is sitting on the bench. The young soldier enters from the left. 5. Mother Courage loses four officers’ shirts and dumb Kattrin finds a baby. After a ferocious battle, Courage tries to stop the Chaplain from taking her officers’ shirts to bandage wounded peasants. Kattrin is frustrated by her mother’s reluctance to donate her possessions and threatens to hit her. Kattrin risks her life to save an infant from a building that has been destroyed by fire. Courage laments the loss of her shirts and snatches a stolen coat from a soldier who has taken some of her alcohol. Kattrin rocks the baby in her arms. 5 Scene 5: The edge of the burning house, smoke drifting in from the left. The officer’s shirts are in the cart, and the plank of wood Kattrin uses to threaten her mother with is visible behind the house. 6. Prosperity has set in, but Kattrin is disfigured. Mother Courage has grown prosperous and takes stock of all the goods she has to sell. As the funeral march for the catholic general Marshal Tilly passes by, Mother Courage and the Chaplain talk about how long the war will continue. When Kattrin is sent to buy merchandise, Mother Courage declines the Chaplain’s proposal of marriage and insists that he should chop firewood. Kattrin returns having been attacked and permanently disfigured by some soldiers. Courage tries to console her by giving her Yvette’s red shoes but she rejects the gift. Courage curses the war. Scene 6: Inside Mother Courage’s tent, with a makeshift bar in the centre. The funeral procession passes behind. 7. Mother Courage at the peak of her business career. Mother Courage has corrected her opinion of the war and sings its praises as a good provider. 6 8. Peace threatens to ruin Mother Courage’s business. Her dashing son performs one heroic deed too many and comes to a sticky end. Courage and the Chaplain hear a rumour that peace has broken out. The Cook reappears and criticises the Chaplain for advising Courage to buy more supplies. Yvette arrives with a manservant having become a rich widow and reveals that the cook is her former lover and womaniser Puffing Piet. Mother Courage’s dashing son, Eilif, is arrested and executed for looting a peasant woman’s house, a crime that brought him rewards during the war. The peace comes to an end, and Courage leaves the Chaplain and follows the Lutheran Swedish army with the Cook. 9. Times are hard, the war is going badly. On account of her daughter, she refuses the offer of a home. The Cook has inherited a tavern in Utrecht, but refuses to take Kattrin along. Overhearing this, Kattrin packs her bundle in preparation to go and leaves a message for her mother. Mother Courage stops her from running away and they leave together without the cook, who goes to Utrecht on his own. 10. Still on the road Mother and daughter hear someone in a peasant house singing the ‘Song of Home’ 11. Dumb Kattrin saves the city of Halle A surprise attack is planned by the Catholic army on the city of Halle. Catholic soldiers force a young peasant to show them the pathway to the city. The peasant and his wife tell Kattrin to join them in praying for the safety of it’s people. Kattrin climbs up on the barn roof and beats a drum to awaken the city. The soldiers offer to spare the life of her mother if she stops drumming, but she continues. They then threaten to destroy the cart but she continues to drum. In the end, the soldiers shoot her dead. Scene 11: Outside the peasant’s cottage Kattrin climbs on to the roof to beat her drum, and she hoists the ladder after her. 12. Mother Courage Moves on The peasants have to convince Courage that Kattrin is dead. She sings a lullaby for her daughter. Mother Courage pays for Kattrin’s burial and receives the condolences of the peasants. Alone, Mother Courage harnesses herself to the empty cart. Still hoping to get back into business, she follows the ragged army. 7 The front cloth: Picasso’s Colombe Au Soleil, which depicts the dove of peace rising over the broken weapons of war. As mother courage pulls off the cart at the end, this was the final image of the production. 8 DIRECTOR’S NOTES by Stephen Unwin Stephen founded English Touring Theatre in 1993, and has directed over fifty professional theatre productions. He is also the author of a number of books on the theatre, and the following section is adapted from his book A Guide to the Plays of Bertolt Brecht published by Methuen. Details on how to obtain a copy can be found at the back of the pack. A Theatre for the Modern World As well as writing some of the most remarkable plays of modern times, Brecht revolutionised the art of the theatre itself. Like all the best playwrights – Shakespeare, Molière, Ibsen – he was a practical man of the theatre. He understood how the theatre worked and was committed to making it into a relevant, provocative and dynamic art form. German artistic life has always had a tendency towards intellectual pronouncements and Brecht’s own theoretical bent needs to be seen as part of this tradition. It should be stressed, however, that Brecht was highly sceptical of abstraction and it is unfortunate that this most tactile and sensuous of playwrights is so often caricatured as an incomprehensible intellectual with his head in the clouds. His experimentation did not take place in isolation and was part of a much broader attempt to create a new kind of theatre, capable of reflecting the ‘dark times’; furthermore, many of his ideas were drawn from elsewhere, above all Shakespeare and other classical writers. In other words it is essential to place Brecht’s various theoretical pronouncements, alienation effect’, ‘epic theatre’, ‘Gestus’ and so on, in context, and take them with a pinch of salt. Brecht was determined that the ‘audience shouldn’t hang up its brain with its coat and hat’; he wanted to create a kind of theatre that could not only reflect reality but help to change it and argued that poetry, character, wit, music, design, and theatricality – everything – should be used to realize this all-important goal: The modern theatre mustn’t be judged by its success in satisfying the audience’s habits but by its success in transforming them. It needs to be questioned not about its degree of conformity with the ‘eternal laws of the theatre’ but about its ability to master the rules governing the great social processes of our age; not about whether it manages to interest the spectator in buying a ticket – i.e. in the theatre itself – but about whether it manages to interest him in the world. 9 ABOUT THE PLAY Brecht did most of the work on Mother Courage and her Children in Sweden in 1939, during the first few months of the Second World War: As I wrote I imagined that the playwright’s warning voice would be heard from the stages of various great cities, proclaiming that he who would sup with the devil must have a long spoon. This may have been naïve of me, but I do not consider being naïve a disgrace. Such productions never materialised. Writers cannot write as rapidly as governments can make war, because writing demands hard thought. Brecht’s instinct for prophecy was never more acute. Mother Courage is set during the Thirty Years War, the extraordinarily complex and wide-ranging religious wars that swept across Central and Northern Europe from 1618 and were only ended by the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648. Over the course of the play, Mother Courage change sides twice, from the Protestant Swedish army to the Catholic forces of the Holy Roman Empire, and back again. Mother Courage Anna Fierling (nicknamed Mother Courage) earns her living by driving a cart from camp to camp, flogging boots, rum, sausages and pistols to the soldiers, striking bargains, lying and cheating, and sometimes even thriving. She is a formidable operator, who can deal with anything that is put in her way. She is unsentimental, canny and shrewd. She is one of the ‘little people’, for whom religion and ideology are alien, and her aim, above all, is to find a way of surviving. Mother Courage is deeply contradictory. Towards the end of scene six she speaks about how it is a ‘long anger’ that is needed, not a short one; this, she hints, is the anger that changes the world. Then, not long after, when her business starts up again, she loses that insight and sets out once more to earn a living. The challenge that Brecht presents is that he has written a character of tremendous human interest and insists that we are critical of her. What he is asking is similar to the Christian notion of hating the sin but loving the sinner: Brecht wants us to admire her toughness and shrewd wit, while criticising her for not recognizing the contradiction she embodies. The facts is Courage lives off the war that surrounds her and she feeds it, and our understanding of this is fundermental to the play’s purpose. Diana Quick as Mother Courage Her Children It is sometimes forgotten that the play’s full title is Mother Courage and her Children and Eilif, Swiss Cheese and Kattrin play a crucial role. Eilif, her elder son, is strong and dashing; but he is too brave for his own good and is shot for doing exactly the same thing in peacetime – breaking into a peasant’s house – that won him praise and promotion in the war. He second son, Swiss Cheese, is a simple soul: honest, reliable and stupid. His decision to hide the regimental cash box seems sensible at the time but leads to his early death, and his mother’s refusal to acknowledge his dead body is one of the most chilling moments in the play. Courage’s daughter Kattrin is one of Brecht’s most inspired creations: in a world gone mad, the guardian of goodness is dumb, resorting in crisis to wild gesticulations and banging a drum. Her death is the play’s astounding climax. 10 Kattrin (Jodie McNee) on the front of the cart Other Characters There are three other important characters. Firstly, the Cook, whose conversations with Courage are as intimate as the play gets. With their experience of suffering, their pragmatism and materialism, the two are perfectly matched and their budding romance is brilliantly drawn. The Cook’s offer to take Courage to Utrecht is not cynical, nor is his refusal to take Kattrin cruel; Courage’s decision to turn him down is, in the context of the war, a terrible mistake. The Chaplain, too, has an important role. He is at his best in time of war, when high morals take second place to necessity; in peacetime, however, he is sanctimonious and hypocritical. As usual in Brecht, it is not religion which is being satirised; it is its double fstandards and denial of material reality. Finally, Yvette’s story is one of the most extraordinary in the play: she is transformed from a pitiful camp whore into the wife of an old Colonel and lady of leisure. Her cynicism is matched by her decency and she uses the one thing she has – her body – to escape the squalid life in which she started. The world of the play The greatness of the play, and the reason why it is one of Brecht’s most enduring masterpieces, lies in something more than its astonishingly well drawn characters, and its passionately held insights. For, like Shakespeare, Brecht’s historical imagination, coupled with his startling dramatic technique, creates the illusion of an entire world, caught in a terrifying and endless struggle between two sets of interchangeable masters, disguising themselves as different religions, but supported by the very people whose participation – and suffering – keep the war going. The result is a twentieth-century riposte to the classical drama of kings and queens, a history ‘written from the bottom up’, and Brecht focuses in detail on real people – soldiers, peasants, tradesmen, prostitutes and even generals – finding ways of feeding themselves and trying to survive the insanity which surrounds them. His characters are often distorted and dehumanized by the world in which they live, but they are astonishingly true to life and recognizable. Scene 6: The Chaplain (Patrick Drury) and the Clerk (Wale Ojo) play draughts inside Mother Courage’s tent. In his extensive notes on the play, Brecht said that Mother Courage was meant to show: that in wartime the big profits are not made by little people. That war, which is a continuation of business by other means, makes the human virtues fatal even to their possessors. That no sacrifice is too great for the struggle against war. 11 Brecht believed that it was not enough to observe the world, it was necessary to change it, and the restrained edginess of this note goes straight to the heart of his intentions. What it does not express is the extraordinary realism of Brecht’s treatment. This realism tolerates no heroism and his analysis is merciless and unsentimental. At times his vision can seem too harsh and uncompromising, too difficult for an audience to be involved in the kind of ‘complex seeing’ that he was so keen to promote. However, when set against the background of a world collapsing into barbarism and war, Mother Courage is an extraordinary vision of the darkest moment of a very dark century. If the twentieth century saw the worst wars in history, Brecht’s play is drama’s greatest plea for peace – and against Fascism. 12 DEMYSTIFYING BRECHT’S THEORIES The Alienation Effect From the outset, Brecht tried to create a kind of theatre which would encourage the audience to look at what was being presented in such a way that they would draw conclusions about the society in which they lived. The result was the ‘alienation effect’ (Verfremdungeffekt, sometimes translated as ‘estrangement’), one of the most misunderstood terms in the Brechtian vocabulary. Essentially, the alienation effect is achieved when the audience is encouraged to re-examine its preconceptions and to look at the familiar in a new way, with an interest in how it can and should be changed. This requires the actor to both inhabit his character and to remember that he is showing it to the audience. The danger with identification, Brecht argued, was that it prevented the actor from commenting on his character and stopped his performance from having an active purpose. It also prevents the audience from looking at the action with any degree of critical distance. Crucially, Brecht wanted his actors to be clear about what each scene – and each moment in each scene – was trying to show and made the understanding of the play’s intentions fundamental to the performance. To this end, Brecht asked his actors to tell their story with as much objectivity as possible: just as witnesses of a car crash or a murder or a football match might describe what they saw, drawing attention to the decisive moments, asking the listeners to look at what happened from a variety of perspectives, helping them come to their own judgments, so in rehearsal Brecht encouraged his actors to present their stories in the third person, prefacing each speech with ‘he said. . . she said. . .’ At other times he asked them to draw attention to particularly important moments in their story, adding ‘instead of responding like this, he responded like that’. These were all just exercises, but could have a powerful effect on the performance. Brecht often asked his actors to be involved in the practical presentation of the play – moving chairs, putting on new costumes, and so on – in full view of the audience. The effect of this is twofold: it helps the actor present each moment with clarity and allows him to demonstrate his own attitude to what is being shown. Epic Theatre The second key notion in Brechtian theory is the ‘epic theatre’. By his own admission, Brecht took much of his inspiration for this from Shakespeare, whose plays are built out of a series of self-contained episodes and jump from location to location unconfined by the Aristotelian unities of time and place. Brecht’s work eschews the smooth inevitability of nineteenth century drama and he argued that only the epic theatre could express the bewildering disjointedness of modern life. The essential point of the epic theatre is that stories are told through a collage of contrasting scenes, whose content, style and approach are deliberately incongruous. A new kind of artistic unity is built out of such conflicting elements: interruptions are encouraged, text is set against action, music is given its own reality, scenery is cut away, unconnected scenes follow on from each other and so on. The point is that by exposing the audience to such diversity, they are encouraged to think independently and come to their own conclusions. Composer Matthew Scott rehearsing the overture with the actors It is a common mistake to imagine that the epic theatre refers only to large-scale historical dramas. Of course, Brecht was interested in writing such plays, and many of his plays cover an epic sweep of history and refer to actual events. However, the term describes a technique more than a genre: The Mother and Fear 13 and Misery of the Third Reich are as much epic theatre as Mother Courage, Life of Galileo or The Caucasian Chalk Circle. Contradictions Brecht recognised that the key to drama lies in the conflict of opposites: one group wants one thing, another wants the opposite and the conflict between the two resolves itself in a third position. He felt that identifying such contradictions was an essential part of the theatre’s role. In the early work this is expressed in an insistent clash of registers: the sentimental followed by the cynical, the intellectual followed by the sensual, and so on. The effect is to relativise any argument that is pursued and to undermine any feeling that is expressed. In his mature work, however, this interest in contradiction and dialectic becomes more positive, and Brecht’s reading of Voltaire and classical Chinese philosophy makes it into an exercise in clear thinking: ‘on the one hand this, on the other hand that’ was, he felt, the approach that stood most chance of approximating to the truth of the world. All of Brecht’s greatest characters are constructed on contradictory principles: the ‘good woman’ Shen Teh has to become the bad man Shui Ta in order to survive; Mother Courage sacrifices her children in order to make a living; Galileo abandons pure scientific pursuit because of its implications; and Puntila, who is generous when drunk, reverts to brutality when sober. The point is that these many contradictions are not the result of poor characterisation – rather, they are realistic portraits of the way that real people behave in a contradictory world. Brecht’s wife Helene Weigel, playing Mother Courage (1949). Weigel had two children with Brecht, and was the co-founder of the Berlinner Ensemble ‘Gestus’ One of the most difficult terms in the Brechtian vocabulary is gestus. At its most superficial, this is close to the English word ‘gesture’: the pointed finger, the shrugged shoulder, the turned back and so on. However, gestus also refers to something deeper: the physical embodiment of the relationships between people in society. Each gestus captures a particular set of interlocking attitudes and the sum total of these provides the audience with a chart of the society that is portrayed. The way that Mother Courage, all alone, hauls the cart round the stage for the last time, still looking for business, is a very particular gestus: a poor production of the play would make this image as pathetic as possible; Brecht’s by contrast, expressed a very troubling gestus, which showed a woman determined to continue living off the war, even though it had robbed her of everything. Telling the Story Dramatic storytelling shows that the things of the world are subject to change, and articulating that process of change and development – of history itself – is an essential element in the Brechtian theatre. Everything that takes place on stage should serve the story, and a production which does not tell the story is one that has failed to learn from Brecht’s example. It is interesting to see from his working notes just how important story outlines were to Brecht’s method of playwriting: much of his preparation consisted of pure story elements, free of opinion, character or meaning. Brecht was eager, however, to distinguish between traditional dramatic story telling – ‘this happens because 14 that happened’ – and the epic style – ‘this happens and then that happens’. His plays are built out of discrete, dynamic units of action, which deliberately do not flow one into the other and he writes with an almost Biblical simplicity which avoids smoothness and allows the joins to be visible Brecht’s emphasis on dramatic action deliberately avoids interpretation: it is the presentation of ‘unvarnished raw material’ that allows the audience to make its own connections. A space is created in which the audience can gain some sense of how the events came about, and how the society that made them can be changed. Scene 9: from the 1949 Berlinner Ensemble production, designed by Ted Otto. Kattrin overhears the Cook telling Courage that she can’t bring her daughter to Utrecht. The half-curtain and the wire pulley device are clearly visible. Playing one thing after another A common criticism of Brecht’s plays is that they are long-winded and boring. One reason for this is Brecht’s emphasis on ‘playing one thing after another’. This means, above all, a way of acting and directing which allows the individual moments to be played for all their worth. This gives the audience the space to look at each element individually, instead of being swept along uncritically by the action. Brechtian productions tend to find detail in small social ‘gests’, whose inclusion illuminates the way that the society operates. These details – paying the servants, bowing to royalty and so on – should not be glossed over, but they can slow down the dramatic action as a result. In his finest work Brecht achieved an extreme economy of means – stripped of rhetoric, dramatically taut, simple and elegant – and they are at their best when played fast. One of the last things Brecht wrote was a note to the actors of the Berliner Ensemble on their first visit to London in August 1956: The English have long dreaded German art as sure to be dreadfully ponderous, slow, involved and pedestrian. . . So our playing must be quick, light and strong. By quickness I don’t mean a frantic rush: playing quickly is not enough, we must think quickly as well. We must keep the pace of our run-throughs, but enriched with a gentle strength and our own enjoyment. The speeches should not be offered hesitantly, as though offering one’s last pair of boots, but must be batted back and forth like ping-pong balls. It should be pinned up in the rehearsal room of anyone attempting to stage Brecht today. 15 TRANSLATOR’S INTERVIEW with Michael Hofmann Michael Hofmann is an award-winning writer and translator of plays and novels. He lives for most of the year in Germany, and speaks the language fluently. This is his first collaboration with ETT. What has been your process for translating Mother Courage? Nothing in any way out of the ordinary. I began at the beginning, and ended at the end. If there was something different about it, it was in the number of goings-over it received. In the ordinary course of things, when I translate books for publishers, they often don’t know what they’re going to get. It’s been utterly different working for Stephen Unwin. We had a wonderful back-and-forth over literally hundreds of things. How does work differ from previous translations? It seems to me people tend to have powerful preconceptions about Brecht. That’s the only way I can account for the way other versions don’t follow Brecht’s words and sentences – as though there was something a priori hopeless about doing that; to me, it would suggest it’s a priori the right thing to do! – but take lines and speeches and completely rewrite them. The major preconception is that Brecht is plain and utilitarian and even a little coarse. Clutching that, you come upon each sentence as a bag full of information to be conveyed, and you don’t scruple to rewrite it. That’s true even of John Willett, to some extent, but it’s powerfully true of the adaptations by various dramatists and also the version that (unfortunately!) gets played in America, by the dreadful H.R. Hays. To me, Brecht is the opposite, he is all style and intention. So I try to be very faithful. As far as I’m concerned, Brecht doesn’t give you cause to be anything else. I’ve never felt myself in the grip of such a powerfully controlling, organizing intelligence as when I translated The Good Person in 1990. You are a native German speaker. Has that been a great help? Well, it’s the basis for my approach. Otherwise, I might well be driven to make some of it up! Seriously, there’s a great array of language in Mother Courage, the ranks and weapons and oaths. Proverbs or other forms of home-made truth. The regionalism of some of the speech – her speech. I think possibly this has the most verisimilitude of any of his plays. I mean Brecht isn’t going to bust himself to get Galileo’s Italy just right, much less a fantasy China with gods and tobacconists. The plays are always exemplary, to do with typical human behaviour, or probable human behaviour. Here, this behaviour is contrasted with or filtered through things you feel people might actually have said in 17th century Germany, the time of the Thirty Years’ War. It doesn’t really matter – I think – but it does give this particular play some of its piquancy. What is different about translating a play rather than a novel? All my translating is for the inner ear anyway, novels, stories, etc. I like to test things by reading them aloud when I’m done. Compared to the theatre, though, that becomes rather metaphorical. It’s a great thrill to hear one’s words spoken in public. Beyond that, it’s Brecht, so we really aren’t talking naturalistic language. It’s a challenge thrown down to the actors. I don’t come from the theory side of it – anything but! – but translating Brecht has shown me what ‘V-effekt’ (alienation effect) and so on means. Everything comes out of the dramatic situation. That’s the underlying geological or meteorological or planetary truth. And then its reflection is shown on single people, characters, individuals, because that’s the way we understand things, not en masse. But the characters are not really individuals, they have something choric about them. They’re possibilities. I think Brecht does something like enlarging his people a thousandfold, and then shrinking them again, like a xerox, or something. But you can tell. They have something purified at the end in their outlines and interests, but also something tampered with. And you can feel that in the language. The characters know that speech is power, and they speak accordingly. And all the time they stand next to themselves in the most fascinating way. I picture them musing to themselves, hmm this is really good, and thinking they ought to write it down! Mother Courage says things that no one individual could possibly say, she talks in a sort of collage speech. That then becomes the actors’ problem, thank god! Mother Courage has been described as having a Shakespearean quality, would you agree? I don’t know that I would go beyond the pervasive intelligence of the speech and the speakers. Continual and vivid argument. To me, that’s what Shakespeare is too. How have you dealt with cultural references that would be incomprehensible to an English-speaking audience? 16 I think while it remains one of the piquant things about the play for a German audience – that, and the fact that you fast-forward 300 years, and find yourself in World War Two – I don’t think the play is reliant on these references. I think I’ve probably generalized most of them, I don’t know. But then the capon is still a capon. Brecht says the truth is always concrete. I’ve really tried not to oppose any of the tendencies of the play, or impose any of my own. There is a great deal of humour in the play. Does this translate well? If it is present in the English, then it will help the play, because humour does well in English, and English audiences crave it. At the same time, it’s not English humour, not juicy humour, and not a distraction or a sweetener. The humour is very much to the point, and I think it’s a matter of symmetry, reflex, almost a diagrammatic humour. Like a kind of cerebral fencing. I don’t make it sound very funny, but it’s a tremendous thing, the opening scene, say, these upright recruiters complaining about the unscrupulous locals, who take the king’s shilling, as it were, but duck out of fighting. There’s a little taste of underlit wisdom about it. It reminds me of Brecht’s poem, “The Solution”, where he suggests the disappointed government ought to elect a new people. What is the significance of the songs? That’s a hard thing to say. Brecht plays always come with songs and poems. It’s part of their patchwork effect, partly it’s to do with the fact that they really want to give pleasure to people. Matthew Scott, our composer, said he thought they were to give people time to pause and take in what they’d seen. 17 ACTOR’S INTERVIEW with Michael Cronin Michael plays the Recruiter, The Old Colonel and the Farmer, and also narrates the introduction to each scene. He is a regular performer for ETT having previously appeared in 10 production including King Lear and The Cherry Orchard. He most recently played Polonius in Hamlet (national tour and West End). A good deal has been written about Brecht’s theories on theatre. Has this affected your aproach to Mother Courage? The fact that Brecht took his work seriously enough to write theoretical essays about it at all makes him a particularly “un-English” phenomenon. I think it’s that word “seriously” that sets alarm bells ringing in some quarters. It would be hard not to be aware of this because, sadly, his theories are discussed more frequently than his plays are produced in this country. Maybe that’s the problem. We don’t see enough Brecht to know him well enough.What influenced me most as I approached this play was having seen the Berliner Ensemble’s production of “The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui” in the early Sixties and having….well, having never seen anything like it! It was an overwhelming experience. It made me laugh, and cry, and think…and it made me gasp with admiration for the actors’ skills in a way I never had before in a theatre. If that was what Brecht’s “theories” could achieve then I couldn't wait to see more of them and above all take part in them. It’s the practice that unwraps the theory. Because, in the end, the theory is devised not for itself but to achieve the plays in a theatre and in front of an audience. The theory is, above all, practical. And that goes for the “politics” too. The play is set during The Thirty Years War, and Brecht wrote it during The Second World War. Have you found it useful to research these periods? Yes, the play is set during a period of The Thirty Years War…remember it’s been going on when the play opens and it goes on after the play concludes…but it’s not “about” The Thirty Years War. I did read one or two history books for a broad outline. I think what astonished me most was realising just how much of Europe the various conflicts covered…from farthest Poland to Northern Italy…and proxy conflicts just about everywhere else on the margins. And the intensity of the fighting and the killing of thousands of civilians. Its unimaginable brutality. Unimaginable? Wrong word. Men committed those acts so they were capable of being imagined. As were the cruelties in Goya’s drawings of the Peninsula War and as were the unspeakable vilenesses we see in photos of Nazi atrocities. All wars bleed into one another. And the tills go on ringing. That is what war is no matter what particular gloss politicians or recruiting sergeants put on it. That’s one of the things Brecht is saying. It still needs saying. Today even more. You play a number of different characters in the play. How do you make them different without making them caricatures? Each character I play has a specific role, a job to do, in the scene in which he appears. But he is still an individual. All Brecht’s people are individuals no matter how many or how few words they speak. That’s important. That’s what stops them becoming merely mouthpieces. They are all complex unpredictable human beings….the situations they find themselves in may be overwhelming but they go on being…just that: human. My job is to show that as well as play the part required by the scene. You have worked with Stephen many times before. How has this rehearsal process differed from previous productions? I think this has been the most detailed rehearsal process I’ve ever been part of with Stephen or anyone else. Each moment of the play, literally, has to be understood, realised precisely and made clear, and offered to the audience. What is happening at any given time on that stage has to be absolutely clear….one thing at a time concretely realised. It’s the accumulation of those moments that give the play its power and makes Brecht’s contract with the audience so specific. Brecht’s theatre company was called the Berlinner Ensemble. How important is it to have a supportive company for this play? 18 I was once shown round the Berliner Ensemble’s theatre in Berlin and my lasting memory of that afternoon is the pride, the intensity of the pride, shown by everyone concerned, for the building and for the work they did. Hard to find outside of a company working together for long periods of time or in the very specific conditions then applying in East Berlin. But I think something as useful and strong can be found in actors’ feelings about the subject of the play they’re performing and their passion for what’s being said. It would be difficult to bring off “Mother Courage” with a cast of sabre-rattlers. Happily, that’s not the case with our company. 19 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR’S REHEARSAL DIARY By Jamie Harper Jamie is the recipient of the National Theatre's Cohen Bursary which will involve him working with ETT and the National Theatre Studio over the coming year. Following his directing training at LAMDA, Jamie won the 2006 JMK Director’s Award and directed 'A Lie of the Mind' at BAC in July. Rehearsal diary It’s Monday the 18th of September and preparations for our production of Mother Courage are in full swing. We’ve been rehearsing for several weeks now and we’re just getting to the point where all the different elements of the work can begin to come together into a unified piece of theatre. Serving the play We started back on the 21st of August (seems like a long time ago now!) with a week of text work. Stephen Unwin (Director) and Diana Quick (Mother Courage) got together to spend some time reading the play in detail to gain a firm grounding on Mother Courage as a character and the shape of the play overall. Much critical ink has been spilled on Bertolt Brecht’s politics, theory and practice but, fundamentally, we have focused on the undoubted quality of his play writing and worked to ‘serve the play’ in our production. As we began to think about ‘serving the play’ we referred frequently to the Model Book of Brecht’s production of Mother Courage for the Berliner Ensemble in 1949. The Model Book comprises the play text, photographs and detailed rehearsal and performance notes. These resources combine to provide a great insight into Brecht’s intentions when he staged the play and without wishing to slavishly adhere to the original we have played close attention to his aims in order to ‘serve the play’ as he intended it to be rendered. Contradiction In our second week, Diana was joined by the other members of the cast and we continued to read the play in detail. At this point Steve began introducing some of the key ideas which have formed the basis of his approach to directing the play. First and foremost, he articulated ‘Brechtian contradiction’. In Brecht’s view, realistic characters are influenced by contradictory impulses, and rather than being seen as a source of confusion these contradictions should be embraced. For example, Mother Courage is influenced by the contradictory impulses of caring for her children and caring for her business. We found that this contradiction was most apparent in Scene Three when she must decide whether to save her cart or her son Swiss Cheese. On the one hand, Mother Courage loves her son and wants to protect him, but on the other hand she must preserve her business and keep hold of her sources of capital in order to survive. Through reading the scene in detail, we saw that as a loving but also mercenary woman Courage is a powerful contradiction and her dilemma in this instance is hugely dramatic as a result of these contradictory impulses. Counter pointing In addition to introducing the principle of contradiction, Steve talked about Brecht’s technique of using counterpoints within scenes. Counter pointing essentially means the simultaneous presentation of different elements of action within the same scene. Scene Two is a good example of this technique as we are shown Mother Courage selling a capon to the Cook at the same time that Eilif drinks wine inside the General’s tent. Steve commented that the challenge in staging these counter pointed scenes lies in ensuring that the 20 audience watches the right action at the right time. For example, it would be very damaging to the scene if the wine drinking within the tent was allowed to draw the attention of the audience away from Courage’s conversation with the Cook. Knowing what you are showing The implication of this for the actors in the cast is that they must be aware of what the scene is intended to show at all times, and this principle of ‘knowing what you are showing’ has been fundamental to the process of rehearsing the play. For example, when we rehearsed the sequence in Scene Three when Kattrin tries on Yvette’s red shoes we discovered that the actor (Jodie McNee) must be careful not to pull focus from the discussion between Courage, the Cook and the Chaplain on the other side of the cart. In this counter pointed scene, we knew that we had to show a young woman discovering her femininity whilst also showing a subversive debate on the subject of the war. This balance was accomplished thanks to Jodie’s awareness of the need to be progressively less ostentatious as she struts back and forth in her new high heels so that the audience’s focus moves away from her to the political conversation on the other side of the cart. (Mission accomplished thanks to principle of ‘knowing what you are showing!!!’) Assistant Director Jamie Harper in rehearsals with actress Jodie McNee (Kattrin) Gestus Having spent two weeks reading the play and discussing the ideas contained in it, our focus in the early rehearsals was to establish a clear physical shape for each scene. Negotiating staging issues like blocking and prop business can at times seem like a boringly technical type of work but in the context of rehearsals for a Brecht play it is absolutely essential for a physical structure to be implemented in the early stages. Brecht wrote extensively on the importance of the ‘gestus’ (the physical manifestation of social relationships) and our production has been strongly focused on clarifying the relationships between characters through rigorously specific physical action. Again, Brecht’s Model Book was invaluable in this phase of the rehearsal process. Photographs from the Berlin production gave us an immediate physical sense of the action in any given scene. For example, in Scene Eight when Eilif is arrested, he is pictured being escorted onstage by a tightly knit squad of four soldiers. This informed our work on Scene Eight and we created our own squad of four soldiers, arranging their physical relationships with Eilif in such a way as to make his fear of imminent execution abundantly clear. One thing after another Once we had created the physical texture of the scenes, we began to look at the detail of the character action (i.e. – who is doing what to whom and why?) At this point Steve introduced another concept which has become one of our rehearsal room catchphrases: ‘Play one thing after another.’ The thought behind this phrase is that it is necessary to delineate and separately demonstrate the different impulses that motivate characters to act. Having discussed ‘contradiction’ in great detail we were all aware of the plurality of objectives that drive people to behave as they do; but in order to retain clarity in the action it’s important to show the divergent forces acting upon the characters independently of each other. For example, in Scene Five, Mother Courage is torn between the contradictory impulses of stopping her daughter from running into a burning building to save a baby and stopping the Chaplain from destroying her expensive officers shirts. This scene shows Courage operating in chaotic circumstances but for the scene to function effectively, the playing of it must be organised, focused and totally un-chaotic. In our rehearsals, we were careful to delineate Mother Courage’s attempt to stop Kattrin from going into the burning building from her subsequent attempt to stop the Chaplain from ‘scrimshandering’ with her shirts. Essentially, the actor (in this case, Diana Quick) must play ‘one thing after another’: she must show one action (save Kattrin) then clearly shift focus to show a 21 different action (save the shirts.) This may seem rather obvious but it is crucially important to play each separate element of the action clearly and fully rather allowing them to all get muddled in the midst of the melee! Conclusion Today it is the 18th of September. We have two more weeks of rehearsal in which time the various elements of the production (text, staging, music and dance) will combine to produce a wonderful piece of theatre (fingers crossed!!) The truth is that putting on plays is an inexact science with lots of trial and error and equal potential for failure as well as success. In the case of Mother Courage, however, we have not only benefited from a superb team of creative and technical theatre practitioners but one of the leading forces in 20th century drama. Bertolt Brecht laid down a blueprint for a particular form of theatre and we have approached this production with the attitude that his lucid innovations in play writing and theatre practice should be used to our advantage. The employment of Brecht’s ideas and techniques has been central to our rehearsal process and I have every confidence that if we can learn from the Master we stand every chance of serving his play with aplomb. 22 DESIGNER’S INTERVIEW with Paul Wills Paul has designed productions for theatres such as the Royal Court and Sheffield Crucible and is the associate designer for the West End musical Guys and Dolls. This is his first collaboration with ETT. What was your starting point for designing Mother Courage? Stephen and I spent a long time working on the script and analysing what was really essential. We wanted to tell the story with only the minimum amount of 'stuff'. Once we had a model of the cart we started to look at various ideas in white card format until what we were left with was essentially a floor and a cyc. Brecht had strong ideas about design. How has this influenced you? Brecht had some strong ideas about theatre design. He believed the workings of the theatre should exposed, much like the sporting arena during a boxing match. He used naturalistic materials, but only what was absolutely necessary to tell the story. For our design we looked closely at The Model Book that Brecht created, and have attempted to reinvent some of his ideas. It is quite important to create 'pictures' on the stage that allow us to highlight various moments of action. The position of the cart is integral to every scene. A sketch for Scene 11 of Mother Courage and her Children (1949 Berlinner Ensemble). Décor is by Ted Otto who successfully translated the epic nature of Brecht’s plays to the stage. Set pieces consist only of what is needed to establish place, and the background is cyclorama. The scene depicted here is Kattrin’s death scene. Was it important to be historically accurate? Although we have set the play during the Thirty years war we opted to create a sense of period and age rather than be totally accurate. Are there any modern references in the design? The basic design is very modern. As an empty space it is clean lined and elegant. The Map has been digitally printed and yet gives us a strong sense of the period. With such an empty stage anything that enters the space gains a great deal of significance. 23 What is the significance of the map? Mother Courage’s journey is very important as is the war that has been going on around her. With very little in the design to suggest the period and the events that were taking place we needed something that would help root it closer to the time. The map allowed us to do all these things as well as providing us with a beautiful backdrop to the action. The play takes place over a number of years. How does the design accomodate this? We dress the cart throughout the production. At times it becomes war-torn, at others it is festooned with new wares. This will tell us a story about the position of Courage at any time. The other design elements will play an important role in this: costume lights and sound will all help to move Courage through the years. Technical Drawing of Mother Courage’s cart What are the considerations for a touring set? That it all fits in a lorry and preferably not be made from glass! It is very important to create a design that is flexible enough to fill the theatres that it goes to. A design that fits snug in one venue will feel lost in another. The simplicity of this design allows it to expand and contract. Some venues have rakes and with the cart this was a major consideration so we decided to anti rake those venues. How do the lighting and costume complement your design? With such a simple space costume brings colour and life to the space as well as a greater sense of period. Lighting allows us to change the atmosphere dramatically as well as create moments of intimacy when needed. Technical Drawing of cart showing measurements 24 COSTUME DESIGNER’S INTERVIEW with Mark Bouman Mark has designed extensively for ETT including Romeo and Juliet and The Seagull. He most recently designed costumes for The Old Country and Hamlet (national tours and West End). When and how do you begin your design process? I begin by reading the script, usually as soon as a director has asked me to do the show, then I'll do back ground research, about the author, circumstances of the play, time it was written in etc. The I start collecting visual images that are linked to the characters in the play. for period productions this can be paintings, etchings of pictures of still existing period costumes etc. The visual images can vary hugely, sometimes it's good to even look into the unusual area's which help you to get an inside to the look of the play. What have been your major influences for Mother Courage? I looked at paintings of the period, some of the northern European 17th Century realist painters are quite useful; Jan Steen, Frans Hals, or earlier painters like Breugel are good to see what the 'everyday' people looked like. Lots of paintings of that period are either royalty of rich merchants, but in this case I needed, the poor and the travellers or pub scenes. The I did more research into the armies of northern Europe around 1630-40's and what they wore (not always uniforms as we know it!) The Cook’s costume Although the play is set in the Thirty Years War, has it been important to be historically accurate? To a certain degree - yes, but if you know your history really well, you'll see that we've been playful with the accuracy. Sometimes it's for artistic reasons or for reasons to make age or poverty clear to an audience that you choose to be less driven by what is right historically but more what looks and feels right for that character. 25 How does your working process with Stephen differ from other directors? I've worked a lot of times before with Stephen, which means we've got a 'short-hand' in talking about style and characterisation. I know Steve well, both he and I love character costumes and are not so much style or trend driven. therefore our meetings are usually short and to the point, we go through each character briefly just to see if we've got the same idea about them, Steve will let me how he sees this person and perhaps we discuss colours of the costume. Once I get into fitting stage I'll show Stephen photo's of the fittings to see if he likes the way I'm going or if he feels different about the characters. How do your designs reflect the changes in the characters’ fortunes? Especially in this play we have what's called lots of 'broken-down' costumes, costumes that look and feel like the person has worn them for years. They are (artificially) made to look dirty, old and threadbare. So with certain characters you'll really see them getting poorer by the way their clothes look worn and broken down from scene to scene. With Mother Courage her self its like a wave, sometimes he has money and has acquired jewellery for instance, sometimes she has nothing left and he overcoat has got holes in an look like it's about to fall apart. Mother Courage’s costume Some of the actors play a number of different parts. How does this affect your designs? When there is a lot of doubling amongst the actors you make sure that each look for an actor looks sufficiently different from the one before. You'll do this by the shapes of the clothes but also by making them wear hats / bonnets and even wigs or facial hair if that is appropriate. Usually each different character the actor plays will have it's own specific characterful look, so you give the audience enough of a clue that this is a totally different person, and not the same guy as before in a different jacket. Some thing you can leave up to the actor as well, they way they talk, stand / slough etc. What has been the biggest challenge when designing Mother Courage? In this case some of the costumes are hired from costume hire places and some will be specifically made for the show. I suppose the biggest challenge is to make sure all costumes look like they are from the same coherent 'world' You don't want to feel like some look much too theatrical next to some which are nicely characterful. When you make a period costume from scratch, its important that the modern fabrics get a period feel about them, so you dye them and paint into them or take the sharp modern colour out of them until they are believable part of the poor dirty 'world' we want to create as being the 1630's 26 DISCUSSION POINTS These discussion points are for the rehearsal room as well as the classroom, and bear in mind that there are no right answers, only healthy debate. Mother Courage is set nearly four hundred years ago and was written by a German during the Second World War. What makes it still relevant to a modern audience? Brecht didn’t name the play after a king or queen, but a street hawker. Why do you think he was interested in her story? Mother Courage constantly has to weigh up her instincts as a mother against her commercial decisions. Try to highlight some of these moments of contradiction in the play. Mother Courage tries so hard and yet loses everything she cares for. Why do you suppose people do things that are against their own self interests? Think of some examples from your own life. During the Gulf War the US and the UK continued to sell arms to Iraq, their supposed enemy (N.G.O. commentator 11/02/00). Brecht said “in wartime the big profits are not made by the little people”. What information can you find to support this? “An estimated 300,000 child soldiers - boys and girls under the age of 18 - are involved in more than 30 conflicts worldwide. They are used as combatants, messengers, porters, cooks and to provide sexual services. Some are forcibly recruited or abducted, others are driven to join by poverty, abuse and discrimination, or to seek revenge for violence enacted against themselves and their families.” http://www.unicef.org/protection/index_armedconflict.html Both Eiliff and Swiss Cheese are conscipted into the army. Find out what you can about this on-going problem. The play takes place over many years, in many different locations, with large gaps in time between scenes. Why do you think Brecht did this? What is the point of the songs and their positioning? When we go to the cinema or the theatre we often get lost in the story and imagine we are one of the characters. Why did Brecht want to combat this? How did he propose doing it? Brecht rewrote some of the play after the first production. For instance, he changed scene 1 so that Mother Courage should be haggling over a belt buckle when her son Eiliff is taken away to fight. Why did he do this and what was he trying to achieve? The play suggests that there is no room for virtue in war. Brave Eiliff, Honest Swiss Cheese and Compassionate Kattrin all suffer because of their virtue. Do you agree with this and is this always the case? EXERCISES One of the criticisms leveled at Brecht was that some of his theories on theatre didn’t work in practice, and that he didn’t use them when he was directing. Brecht’s riposte was that he used what worked. Although these exercises are more useful in a workshop scenario than the rehearsal room, they should help to give a better understanding of how his theories can work on stage. Warm-up A good warm-up exercise that gets everyone in the right mind set is body part leading. Begin by walking round the room, leading with the head, then the nose, chin, shoulders, stomach, groin, feet and hands. Try to isolate each leading body part and stretch the movement as far as possible. Question what characters are suggested by each movement, and what their status is. Now ask each student to approach a chair leading with one body part, sit and look at the audience as that character, then move away leading with a different body part. If you want to develop this further, create improvisations where these characters are introduced to each other. Objective: Immediately breaks the ice, and makes the students aware of multi-role playing and status. Example: The actor playing the Narrator introduces each scene, and then immediately begins playing his character. In this way he lets the audience know that he is an actor playing a part, his attitude to that part, and also the character’s status. 27 Exaggeration The exaggeration and reported speech exercises are Brecht’s own. Begin this exercise with everyone sitting down in their own space, miming eating with a knife and fork. Try to make the mime as naturalistic as possible, then slowly let the knife and fork become enormous, and then tiny. Repeat the exercise, brushing your hair. Objective: ‘The truth is concrete’. Brecht wanted the audience to be aware of the social position of each character within the hierarchy, and the objects that characters use reveal this clearly. Example: Courage has a purse round her waist, because as head of the family she controls the finances. She is a street hawker, and has to be ready to make a sale at any time. Reported speech In pairs improvise a scene in which two people who have not seen each other for ten years meet at a bus stop. Each actor narrates or reports exactly what they themselves are doing, and puts ‘he /she said’ before they speak. For instance: Actor: (to the audience) ‘He sat on the ground’ (the actor sits) or Actor: (to the audience) ‘He said “It’s good to see you” (turning to actor 2) It’s good to see you’. When ready, introduce thoughts aloud. These thoughts might be in contradiction to the dialogue. For instance: Actor: (pointing at actor 2) ‘He hated the sight of him (turning to actor 2) How good to see you!’ Try to use body part leading and freeze frames to suggest character and status. Objective: To make the actor and audience view the character from a critical distance. Example: Although this is an exercise to be used in rehearsals rather than performance, Brecht uses a similar device with the narrator. Focus This exercise was devised by Dario Fo. Seven actors are needed. Begin with actor one lying on the floor having been hit by a car. Actor two is the driver of the car. Actor three was crossing the road and witnessed the accident. Actor four also witnessed the accident, but believes the blame lies with actor three for making the car swerve and lose control. Actor five arrives and, claiming to be a doctor, begins to treat the injured person. Actor six, also claiming to be a doctor, is horrified by the actions of actor five and uses the patient as a dummy to demonstrate the correct procedure. Actor seven is a policeman who tries to sort out the mess. You can freeze frame the scene at any point to prompt ideas from the audience. It is up to actor one to finish the scene. Objective: By switching the focus from actor one to the other characters, the scene becomes less emotional and naturalistic, and makes the audience actively involved in the outcome. It also demonstrates the use of humour as a distancing technique. Example: In scene 11 The focus switches from Kattrin’s heroic drumming to the Farmer’s feeble attempts to mask the noise by chopping down a tree. Gestus 1. In groups of five, devise a scene in which a high status character is dressed by his/her servants. As clothing and props are added, the servants must ask for something. However the character cannot speak until the last item has been put on, as this contains the essence of the character. For instance, the key piece for Winston Churchill could be his cigar. When this is added, the actor responds to the servants and freeze frame a gestus. Objective: To establish a history and social status of the character. Example: The staggered dressing of the Colonel in scene 6, with the moustache added last. 2. In threes, explore a moment that involves a decision. For instance deciding whether to break up with someone, or considering whether to hand in some lost money, or owning up to losing a friend’s ipod. Then start to explore the contradictions: you could really use the money, but you may be rewarded for handing it in, and what if someone has seen you pick it up? Or you don’t want to lie to your friend, but the ipod was a new 28 Christmas present. Now try to represent this indecision as physical actions. It helps to begin with freeze frames. Objective: To demonstrate the contradiction in Gestus. The most famous example of this was in the 1949 Berlinner Ensemble production. Mother Courage (played by Helene Weigel) gave a silent scream when she heard the shots of the firing squad that kill her son Swiss Cheese, but was unable to vocalize her pain for fear of giving herself away. Example: In scene 5 Mother Courage is torn between saving Kattrin from the burning house, and stopping the Chaplain from ripping up her best shirts for bandages. Themes First get the whole group to brain storm some themes of the play. Then in groups of five, devise a scene around one of these themes. Begin by freeze framing the beginning, middle and end, and then add devices such as montage, captions, music, song, reported speech, narration and juxtaposition. Use whatever devices best distance the audience. Finally, play with switching the order of the scene and decide where you want to place the audience. Objective: To demonstrate how the content of the scene determines the form, not the other way round. Example: In scene 4 Mother Courage sings the Song of the Great Surrender to disuade a young soldier from making a complaint. This song demonstrates how short the anger of the soldier is: by the time Courage has finished, it has evaporated. The song also helps to show Courage’s bitterness and her realism. She learns by instructing, so that she too leaves without making a complaint. Script work Each scene in the play can be played independently as a separate unit. In fact that was Brecht’s intention. After reading through scene one, consider the following; What is Brecht trying to show in this scene? Mother Courage tries to protect her children from the recruiters but loses her son to the war whilst she is busy doing a business deal. What does this tell us about the relationship between war and business? What do you think about the way characters behave? Should the soldiers take Eiliff? Why doesn’t Swiss Cheese do something to help? Is Mother Courage foolish to fall for the soldiers’ trick or is she just trying her best to survive? How could you stage the scene to make the audience aware that they are watching a play? Brecht suggested having the actors getting changed in to costume in full view, or having actors speak directly to the audience. How could the song be played separately from the scene? What are the contradictions in this scene? The great disorder of war begins with order. Mother Courage needs the soldiers to do business but knows they want her children, and she is proud of her sons’ physical prowess even as she is aware of the danger. Kattrin sees her brother being taken away but cannot speak. Can you identify the different Gestus that each character embodies at each moment? The way the recruiters discuss the poor quality of recruits is different to the way they eye up Eiliff and Swiss Cheese. Mother Courage’s challenges them with a knife but later sells them a belt buckle. Kattrin’s expression when she realizes that Eiliff is being taken away is different to her reaction to being put in the harness herself. Courage makes a sale but has to acknowledge that she is responsible for losing her son. Can you define each element of the story, so that every moment can be played clearly? When Mother Courage makes the sergeant draws lots, she is trying to dissuade them from taking her sons, and also Eiliff from joining the war. When she is tempted to sell a belt buckle, she must at first be suspicious, before being overcome with a desire to make a sale. Brecht referred to this clarity of action as ‘playing one thing after another’. 29 CHRONICLE 1898 10 February: Bertolt Brecht is born in Augsburg, Germany 1917 Russian Revolution Studies as a medical student at Munich University 1918 End of First World War Military service as medical orderly Writes BAAL and THE BALLAD OF THE DEAD SOLDIER 1919 Versailles Treaty Birth of Brecht’s illegitimate son Frank Writes DRUMS IN THE NIGHT 1920 Nazi Party founded Death of Brecht’s mother 1921 Russian Famine Leaves University without a degree and moves to Berlin 1922 Mussolini comes to power in Italy Directs Arnolt Bronnen’s PARRICIDE, but is taken off the production Premiere of DRUMS IN THE NIGHT in Munich Marries Marianne Zoff 1923 Hitler’s unsuccessful Beerhall putsch Premiere of IN THE JUNGLE in Munich Daughter Hanne is born Première of BAAL in Leipzig 1924 Stalin becomes General Secretary of USSR Directs THE LIFE EDWARD II OF ENGLAND in Munich Meets Elisabeth Hauptmann Stefan Brecht is born 1926 Germany admitted to the league ofNations Co-directs BAAL in Berlin Premiere of MAN EQUALS MAN in Darmstadt and Düsseldorf Starts to read Karl Marx’ DAS KAPITAL 1927 Meets Kurt Weill Premiere of MAHAGOONY SONGSPIEL Divorces Marianne Zoff 1928 Premiere of THE THREEPENNY OPERA in Berlin 1929 Wall Street Crash Marries Helene Weigel Writes SAINT JOAN OF THE STOCKYARDS 1930 3 million unemployed World Premiere of THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CITY OF MAHAGONNY inLeipzig Birth of daughter Barbara 1932 Nazi election victory THE MOTHER opens in Berlin. Meets Margarete Steffin and Sergei Tretiakoff 1933 Hitler appointed Chancellor Dachau opened 1935 The Nuremberg Laws on Citizenship and Race passed The Brechts leave Germany via Prague. Go to Paris and buy house on Fyn Island, Denmark, New York première of THE THREEPENNY OPERA Meets Ruth Berlau German citizenship renounced by the Nazis Visits New York for the Theatre Union’s première of THE MOTHER 1936 Spanish civil war 1937 1938 Co-founds DAS WORT Starts writing LIFE OF GALILEO German invasion of Sudetenland Kristallnacht Première of eight scenes of FEAR AND MISERY OF THE THIRD REICH in Paris Finishes first version of LIFE OF GALILEO 30 1939 German invasion of Poland triggers Second World War Moves to Stockholm Death of Brecht’s father Writes MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN 1940 Battle of Britain 17 April: move to Helsinki Writes THE GOOD PERSON OF SZECHWAN 1941 Germans invade Soviet Union Japanese attack Pearl Harbour Writes THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF ARTURO UI Premiere of MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN at the Zürich Schauspielhaus Leaves Finland for America, via Russia Meets Charlie Chaplin 1943 Germans defeated at Stalingrad, Allies land in Italy World Premiere of THE GOOD PERSON OF SCZECHWAN at the Zürich Schauspielhaus World Premiere of LIFE OF GALILEO in Zürich Death of Brecht’s son Frank on the Russian Front 1944 Normandy Landings Writes THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE Brecht’s son by Ruth Berlau lives for only a few days 1945 Hitler commits suicide Total defeat of Nazi Germany PRIVATE LIFE OF THE MASTER RACE (American adaptation of FEAR AND MISERY) in San Francisco and New York 1947 Marshall Plan for reconstruction of Europe Première of LIFE OF GALILEO with Charles Laughton in Los Angeles Brecht appears before the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington 1948 Russian impose blockade of Berlin Returns to East Berlin Writes A SHORT ORGANUM FOR THE THEATRE 1949 Founding of West Germany and East Germany Directs MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHIDREN with Helene Weigel at the Deutsches Theater 1950 Outbreak of the Korean War Takes Austrian citizenship Directs MOTHER COURAGE with Therese Giehse at the Munich Kammerspiele 1951 Test of Hydrogen Bomb Directs THE MOTHER for the Berliner Ensemble at the Deutsches Theater 1954 Directs première of THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE for the Berliner Ensemble at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm MOTHER COURAGE visits Paris International Theatre Festival 1955 Signing of the Warsaw Pact Awarded the Stalin Prize Brecht taken ill 1956 Khrushchev’s ‘secret speech’ denouncing Stalin The Berliner Ensemble visits London 14 August: Brecht dies of heart attack 17 August: Buried in the Dorotheen Cemetery in Berlin 31 FURTHER READING The collected works of Brecht have been translated and are published by Methuen in eight volumes. Volume five contains Mother Courage and Life of Gallileo, translated by John Willett. Work by Brecht himself: Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aeshetic, Translated by John Willett, Methuen London 1964. This contains Brecht’s most important theories in his own words. The Messingkauf Dialogues, translated by John Willett, Methuen 2002 Brecht on Film and Radio by Marc Silbermann, 2000. From Germany to Hollywood, this covers his writings on the media that was transforming arts and communication. Brecht on Art and Politics by Tom Kuhn and Steve Giles, 2004. Contains new translations with useful short summaries to each section. Other Work: Cambridge Companion to Brecht, edited by Thompson and Sachs, Cambridge University Press 1994. A good general guide, easy to use as a reference. Understanding Brecht by Walter Benjamin, Translated by Anna Bostock, Verso london 1998. Short and concise, contains a useful analysis of Epic Theatre and Brecht’s political beliefs. Brecht: A Choice of Evils, Martin Esslin, Methuen London 1964. Written just after Brecht’s death, a good early study of his work and the different attitudes to his writing and his communist beliefs. Brecht Chronicle, Klaus Volker, Seabury Press, New york 1975. The most complete biography containing references to his personal, political and artistic life. The Life and Lies of Bertolt Brecht, John Fuegi, HarperCollins, London 1995. A fairly sensationalist, and definitely unauthorised view claiming that most of his plays were written by others. Worth a read but not to be taken too seriously. Online: http://www.google.com/Top/Arts/Literature/Authors/B/Brecht,_Bertolt/ Google compendium of different websites including translations, biographies, essays, discussion forum etc. http://german.lss.wisc.edu/brecht/ The international Brecht Society website. http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2129258,00.html DW-World.DE, website celebrating the 50th anniversary of Brecht’s death, includes an article about his time in Hollywood. A Guide to the Plays of Bertolt Brecht By Stephen Unwin (Methuen 2005) RRP £9.99 A guide to all of Brecht's key plays that sets them in their historical, dramaturgical and political contexts. Stephen Unwin provides a clear and readable guide to Brecht's plays that will prove invaluable to the student, teacher and theatre practitioner. Grouping and analysing plays chronologically according to their context, Unwin also considers Brecht's theory and looks at his impact and the legacy that he left. The Guide covers: Three Early Plays and Expressionism; Two Music Theatre Pieces and Kurt Weill; Marxism and the Theatre; Opposition Plays; Five Great Plays; A Late Masterpiece; Theory and Practice; Brecht's Legacy; A perfect companion to the plays of Brecht for the student and theatre practitioner; Clear structure and readable style; Written by the Artistic Director of English Touring Theatre and the author of a range of theatre studies books. 32

© Copyright 2026