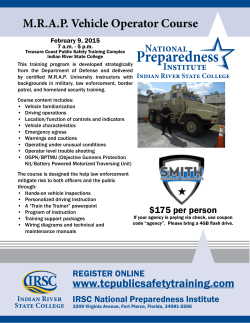

law, enforcement and education. The appendices contain a number