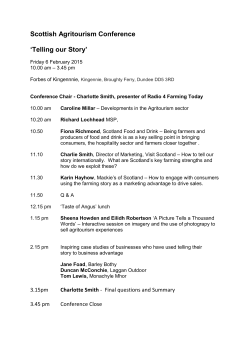

The Right Help at the Right Time in the Right Place