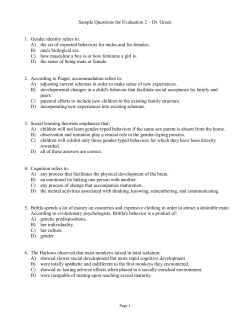

Growing Up in Scotland - The Scottish Government