Why that? Why there? Why then? The politics of early medieval

!∀#∃∃%&∋&∋&∋

&(

(

(&)∗(

!∗!#%)(+,

−

+&

.&

∀/.&

(& (01

/

!0

!2!

3)4/5678∃9

:

Why that? Why there? Why then?

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

Marfin Carver

,

b

The hypothesis presented in this paper has already appeared in various

fragmentary forms (Carver 1986,1993,1998b), but has not hitherto been drawn

together, so it is fitting that I should k y to do this in honour of my best teacher

and most telling critic. After all, it would not do for Professor Cramp's

Festschrift to be too burdened by flattering emulation; it should contain

something exasperating as well. So I look forward to her leafing through these

pages with growing despair, culminating in the tart response familiar from my

carefree student days: 'really Mr Carver, I have no idea what you are talking

about', meaning: 'actually, 1 know perfectly welI; you on the other hand ...'

In brief, the hypothesis concerns the history of the early medieval period

in north-west Europe and our ability to read it from archaeology, or more

specifically from its major inves.tments such as burial mounds, churches,

illuminated manuscripts and sculpture: the word 'monumentality' of my title

is intended as shbrthand for aII these things. Confidence in the idea that

monuments had (and have) a meaning beyond some vague celebration of an

individual or propitiation of an unseen omnipotence has been growing among

prehistorians (e.g. BradIey 1993), and is an accepted feature of the historic

period. We know that monuments are more than passive memorials because

written commentaries, poetry and inscriptions declare their active purposes for

us. Monuments comprise the vocabulary of a politicaI language, fossilized

versions of arguments that were continuous and may Rave related more to

.what was desired than what had occurred (Carver 1993).At the same time, we

need not suppose that the expression is necessarily so subtle, sceptical or to use

a fashionable word, ironical, as to lose all hope of making equations between

a socieiy and its ideas. That architecture, sculpture, burial mounds and

brooches have messages beyond the functional which are dependant on their

social, economic and above a11 their ideological context was never an issue: to

understand their real meaning is the goal and the aim of each generation that

\

Martin Carvw

studies them. It is very likely that the motives .I attach to the construction of

the monuments to be discussed are equally inadequate characterizations of the

profound stresses that motivated and were concealed by their makers. That

said, the monuments are what survive, and our story must temporarily keep

the candle burning untiI their story can be told.

Some assxlmptions

The argument requires a number of assumptions to be declared. First, all

archaeologists are obliged to acknowledge that whereas their efforts have the

advantage of generating new evidence, there is never a good moment to argue

from it; even newer evidence can quickly take the shine off too detaiIed a

model. Reasoning from documents has the disadvantage that so few survive,

but the advantage that no new sources are likely to appear suddenly in the

midst of the six-year-long composition of a major synthesis. Archaeological

reasoning and historical reasoning have naturally different rhythms, and the

world is a more interesting place because of it. But, in order to offer a

historically acceptable model, the archaeologist is oLliged to assume that it is

legitimate to argue from the material culture we have; to assert that in certain

matters, such as the occurrence of churches and burial mounds, the

distribution will not now alter markedly: that what we have is not exactly

what there was, but is an acceptable representation of what there was. Having

declared this assumption, the archaeologist should be permitted to develop a

model on evidence that is partial; the documentary evidence is partial too, but

it is legitimate to afdempt to write history from it.

A second assumption is that the repertoirgbf material culture at our

disposal is heterogeneous and cannot be interpreted through a single

theoretical exegesis. Not every object or site has an equal claim to be treated

as intentionally expressive. If the Sutton Hoo mound 1 burial or the

Lindisfarne Gospels can be seen as having agency, representing material

culture in its active voice, there is no need to impute the same intentions to a

spade or a spindle whorl. The old definition of a 'culture', pulled tlus way and

that since Gordon ChiIde used it the preface to The Danube in Prehistory (19291,

can be seen as neither all cultural, nor always seeking identity, status or

affiliation, but multi-purposed, a set of different statements addressing

different audiences or none. If economic information is incorporated in the

layers of midden heap, political meaning is most likely to be embedded in sites

and objects of high investment and public access. In our period, the prominent

candidates are burial mounds, jewellery, churches, illuminated manuscripts

and sculpture. These appear not only in a single place at successive times, but

at the same time in different places. If assumption number 1 is tenable this

variation has a meaning and was intended to have one.

If the choice of the vehicle of expression is intentional, how far is it sui

generis and how far is it owed to the emulation of the neighbours? This

'

The Politics of Early Medieval Mdnumenfality

3

depends firstIy on whether the neighbours are visible, and the third

assumption I make is that in early medieval, northern Europe they were. The

Anglo-Saxons knew about the Romans, the Irish, the Picts, the British, the

Franks, the Swedes, the Danes and the Norwegians at both a general and a

personal level, and we can infer this both from books (Bede) and from graves

(see, for example, Hines 1984). It is these contacts and the transmissions

between them that allow us to suppose that the commissioners of seventhcentury monuments could fish in a large reservoir of ideas. George Henderson

invokes the broad range of stimuli available to the composers of the Book of

Durrow in AD 680: 'Discrete national traits, in design, techruque and the

motifs, came into conjunction in the peculiar, small-scale, packed

selecba,of

circumstances of the British Lsles, with its ever-changmg political scene, under

the constant cohesive influence of the internationally active Christian church,

writing and speaking Latin to all ears' enderso son 1999,53). But .to these same

people, the local traits of Scandinavia an$ Saxony were also visible or at least

were known - the patterns on cremation urns, the wrist clasps and squareheaded brooches which had been worn by East AngIian nobles. The bracteates

or guldgubbe made in Fyn are sources for Insular Art potentially no more

obscure than Coptic bowls or stamped Mediterranean pottery. So why were

their ideas not recycled on the pages of the gospel books? The animals of the

Sutton Hoo shoulder clasps and purse lid and of the Durrow carpet pages are

links in the same technician's chain. But a great deal more of the Sutton Hoo

menagerie, on helmet, sceptre, and sword was not adopted by the Christian

artisans. Eastern Christian figurative art was known to the kings of East

Anglia, as can be seen from a sixth-century bucket found in a field a few

hundred metres north of Sutton Hoo (Mango et al. 1989). But it was not

incorporated into the Sutton Hoo jewelIery. The point is an obvious one. The

Anglo-Saxons were not 'eclectic' in the sense of taking motifs at random from

some workshop floor or exotic street scene. They were not indiscriminately

'influenced' by things they had seen in the halls of Danish relatives or on trips

to Rome. They were creative and seIective, not eclectic, but choosy. There was,

potentially, a broad range of accessible options and since the different options

were equally available, the choice which was actually made must have a

meaning.

The next assumption is that the repertoire of possible choices does not

need to be contemporary; in other words the maker of expressive artefacts and

monuments can also fish in the pool of the past. The metal-smiths of later

Celtic Britain and IreIand can revive La T h e styles after an interval of 500

years, just as Roman motifs, lettering, ornament and pottery are reintroduced

in seventh-century Northumbria, the courts of Offa and Charlemagne, the burh

of Alfred, and in numerous subsequent renaissances (Carver 1993). It was

recently argued that the notched shield seen on the St Andrews Sarcophagus

derived from something last seen (so far as we are aware) in the Iron Age of

southern Britain (Carver 1999a). There are two ways in which this transmission

4

Martin Carver

can be achieved, the most easily acknowledged being swvival of the obje~tor

site itself. Bailey (1992) suggests a 'co,nseflatism' to account for the gap

between Sutton Hoo a n d Durrow (see below), while Henderson prefers to see

the pqsrnjssion occurring via suryiyingpat&rn books (Henderson 1999,SO).

Roman things no doubt turned up or were dug up from time to time, certainly

when former Roman sites were being-redeveloped f r ~ m

the- t~-th-century

pnwards; this easily explains why the form of late Saxon pottery was drawn

from Roman, not Frankish models (Carver 1999b, 42). The argument has been

extended to sites; former prehistoric ceremonial centres being commandeered

by later authorities for their own legitimation (Bradley 19881, and it is likely

that the Anglo-Saxons had quite a sophisticated knowledge of 'landscape

archaeology'. Bronze Age burial mounds were suitable places for the emulation

of Pagan status, wliile Christian missionaries should be assigned old Roman

forts like Burgh Castle (Johnson1988).

It is more difficult to use the 'swvival' argument to explain the readoption

of certain other practices such as ship burial, arguably seen previously in that

form neither in Scandinavia nor Britain when it was practised at seventhcentury Sufdon Hoo and Snape. Here the assumpiion required is that the idea

of ship-burial was present in the previous century and perhaps long before,

but not thm practised. The archaeologist cannot excavate these ethereal

images, which are transmitted through unrecorded space like cluldren's rituals

in the playground (Opie and Opie 1977). Unless we suppose an early

archaeological expedition to the Pyramid city at Gizeh, the idea of shp-burial

came out of the heads of people and became archaeologically visible only

when it was reified in some moment of exceptional stress. Ship-burial is

therefore not a custom but a statement in context, and our interest in it isnot

so much in the innate meaning of the ritual as the meaning it had for seventhcentury East 'Anglia: why that, why there,. why then? (Carver-1995),

The contextual explanation may be thought to deserve precedence over the

cultural. For example, there were burial mounds in the fifth?sixth, and seventh

centuries in Britain, but this is not simply a 'burial custom' that evolves or

endures. The style and location of seventh-century mounds is different from

*heir Anglo-Saxon predecessors, being larger and more solitary (Shephard

1979). In any case, the burial mound does not have to carry exactly the same

significance in the seventh century as in the sixth: it depends what else was

happening. At Sutton HOOthe use of burial mounds can be deemed

'expressive' or even ~ o l e k c aon

l two counts: first they represent a highex:level

of investment than the mounds of previous centuries, and second, they are

constructed a t a time at which quite different monuments are being

constructed in adjacent lands, for example in Kent. By contrast, Kent, rich in

burial mounds in the sixth century, is investing in a new repertobe in the

seventh - the apsidal churches.of Canterbury.

If this is merely to say that mon~lmentshave political meaning, and the

choice of monument reflects a political agenda, that is already a great deal for

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

5

some to accept. But it is auo-qatic for what follows. I want to propose that

early medieval investments, prestige buildings and artefacts, can be used to

write political as well as cultural lustory, and that if this is acceptable, we can

paint a picture of confronted

-- poiities pursuing different ag~ndasduring the

f i f h to the eighth centuries.Eoth iviilun the %and 'of ~ r i t a i nand beyond.

Fig. 1.1. Monumental mound-burial in Briiain in the sixth and sevenih

cenfxries AD (Carver 1986, after Shephard 1979).

\

Reacfionay mound-building

The conflated version of Shephard's map (Fig. 1.1;Carver 1986) shows a trend:

cemeteries with numerous small burial mounds are present in sixth-century

Kent, and larger more solitary barrows are built in the late sixth into the

seventh century outside Kent. We should seek some explanation for this

Fig. 1.2. Bihrial under large mounds, sixth t o lak seventh century AD in

the Rhineland {Bohme 2993, Abb. 101).

apparent contrast, and can easily find one in the pivotal ideologicagevent of

the period - the documented arrival of the Christian mission from Rome in

597. If Christianity depressed1barrow-budding in Kent, it provoked it among

the umonverted neighbours in a more militant form. Taplow, Sutton Hoo, and

many other monumental constructio~of around 600 in Saxon lands, can be

read as reactions against the Christian mission (Carver 1986, k998a, 1998b).

The work of H. W. Bohme enables us to propose a similar process for the

~hineland(Bijhme 1993; Miiller-Wille 19981, @re the building of monumental

mounds begins at the ~ n mouth

e

in the fifth century and moves s t e a a y

upstream, arriving in Switzerland by the eighth (Fig. 1.2). In an equally

thorough census, Bohme has also tracked the building of early chwchesiq the

same area; this second lund of monument can be seen to sbadoy the first - the

earliest

churches replacing the earliest barrows and the latest chwches

.

following the later barrows (Fig. 1.3). This should mean not just that churches

replaced monumental barrows: they provoked their construction in the first

place. We can imagine h s 'bow-wave' effect taking many forms. When the

' mission of Adam of Bremen arrived at the ceremonial cenbe of Gamla Uppsala

in Sweden, the grotesque sacrificiaI practices were noted: apimals and men

were hung on a great tree - and it was naturally assumed that this was a first

encounter with an annual barbaric custom. Such it may have been, but the

practice of sacrifice has been hard to find archaeologically, except on a small

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

7

Fig. 2.3. Burial in or in associafion wifh churches, sixth to l~feseventh

century, in the Rhinellznd (Buhme 1993, Abb. 99).

,

scale - for example animals slaughtered and included in graves. Possibly the

text is intended to exaggerate the barbarity and justify the incursion. But if the

event really took place, it might have done so out of the insecurity and anxiety

caused by the Christian presence itself. The sacrificial practices were not so

much discovered by the Christians as provoked by them. The same might have

been true of Cortks in Mexico; the increasing orgy of Aztec sacrifice being

caused by fear of'the alien adventurers who denounced it.

Leslek Pawel Slupecki (1997) argues for similar processes in a study of the

impact of Christianity on the eastern Slavs, and cites earlier work along the

.same lines (for example H. Jowmianski in 1979): the observed surge in Pagan

religion was an ideologcal response to the advances of Christianity. Human

sacrifice increases, temples are built and the role of the priest develops. There

was even an example of altars to pagan and Christian gods being placed in the

same temple, as had been notoriously perpetrated by the East Anglian king

Raedwald in similar circumstances ,WOgntururi earIier and a few thousand

rnilesxestwards (STupecki 1997,186). The p r o x i m i ~ o f~hristi&f~rovoked

opposition to its ritual power, a menace occasionally molified by dressing in

its clothes.

It would not do to ascribe every monumental burial mound in northwest

Europe to anti-Christian anxiety; but it must have played an important role.

The general map produced by ~ o b e rv&

t de Noort (1993; now amended Lutovsky

Martin Carver

Fig, 1.4. Distribution of dated burial mounds and burrow cemeteries

(including some graves with ring ditches, thought to have been mounds)

(Lufovssky 1996, fig I b).

1996) shows a chronoIogica1 trend which for the most part pre-echoes

conversion (Fig. 1.4),but not every case fits the model. The mounds at Hogom

in Medelpad, Sweden (Ramquist 1992) are too early (at fifth or sixth cenfmy)

to be reacting to a Christian menace. But that is not to say that no equally

stressful circumstances were involved; for every monument we need to seek

both the impetus and the motive.

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentali~

9

This argument suggests that the building of a monumental burial-mound

is best regarded as a historical event, the result of the conjuncture between a

set of beliefs and the circumstances of the time. The circumstance most likely

to provoke these monuments is political insecurity, and Christianity with its

declared programme of conversion and Roman imperial associations must be

counted among the provocative forces of the age. Is it right to regard the

signals of barrow-burial as 'poIitical" (in that they are seen as mainry

expressing power, alignment and allegiance), rather than ethnic, customary or

religious? They could be seen as ethnic in the sense that a certain group of

people who regard themselves as related might act togekher; or customary, in

that barrow burial had existed previously amongst those people as a smallscale ritual ready for political inflation when needed; or religious in the sense

that a common set of beliefs might be implied in order fox similar events to

provoke a similar response. But these factors are neither necessary nor

sufficient for monumentaIity, and they do not explain why monumentality is

intermittent. Gqjy .politics-are sensitive to events, so politics should Iie behind

change. If political motivation has primacy, ths would help to explain why

pedpl+ Iiving in different lands can use the same

-- -s i ~ a lh-emulation

s

of each

other, without c l a i m 3 ethnic affiliation or acknowledging the same gods. So

to

Sutton Hoo, forexample, we do not need to claim that East Angles

worshipped,, Odin or were Swedes; only that they well understood the

philosophies of Pagan thinking and the language of its monumentality. In the

sixth century the East Angles muttered their allegiance to the ideoIogy, but. in

the seventh they felt obliged to shout it.

-

-L

I

l

m

A monumsntal hiatus

Sutton Hoo ceased to be used as a high-status burial ground about AD 625,

and became for the next 200 to 300 years a place of execution: the ideological

struggle had been' resolved in favour of ~igorous

_ _ Christian

--- kingship

.

(Carver

1998a). In &g- aftermath to the documented conv&iion, however, and not just

in East Anglia, there is a curious lull in material expression of nearly half a

century from about 625 to-675, when soaety seems to be holding its breath.

Furnished graves have proved difficult to assign to this period (Geake 1997,

124), as have churches (Taylor and Taylor 1965), sculpture (e.g. Hawkes 1999,

404) and illuminated manuscripts (Alexander 1978). It is has to be assumed,

nevertheless, that churches were being built and monasteriesfounded, because

the documentary record tells us so. T h e sixtl-century monasteries of Iona and

Wluthorn were active in the north and the episcopal centre at Canterbury

active in the south. A church of wood was built at _Yockjn 626 and a bigger

one planned in stone. Aidan w a s in Lindisfarne and Birinus at Dorchester in

635. Ceanwealh built the church of St Peter at Winchester in 648. Christianity

became compulsory in Kent in 640; temples were destroyed in Essex in 665.

Barrows may also have been built: Fenda kept the pagan flag flying until his

_--

+

10

Martin Carver

death at The Winwaed in 655. But investment in objects and constructions on

the monumental scale are difficult to find on the ground, and rnaybg ma.tgria1

expression was deliberately modest. Perhaps this was a period in which the

actual message of Christian purism was briefly effective, and even the

aristocracy lived briefly by precepts of generosity towards others and reserve

in celebrating themselves.

On the boundaries, as we have seen from the case of the Rhineland, a

more Iively monumental confrontation may take place. A British exampIe

seems to have been discovered by Edwina Proudfoot in the course of her work

at the Hallow Hill and amplified in a brilliant paper by the late Ian Smith

.(Proudfoot 1996; Smith 1996). Here a range of different monument types square-ditched barrows and Class I symbol stones in the north and long cisr

graves and stone crosses. b the south are confronted across a seventh-century

boundary running across Fife. Objectionshave been raised that long-cist burials

do not have to be diagnostic of Christianity, because they are found in

prehistoric variants and are distributed further north. But they certainly

resemble the Christian cist-graves of the Alpine region (Carver-1987) more

closely than any Bronze Age predecessor. If it were an attribute of Christianity,

the long-cist would be found to move over Scotland revealing the itinerary of

successful conversion. The early Christian pressure on the Picts intimated by

Bede (HE U1.4)is persuasively captured in Smith's snapshot of a monumental

frontier (Fig. 1.5)

The Northurnb r i m forum

Further south, the monumental machine seems to start up again at the end of

the seventh-century. Ripon an$ Monkwearmouth are founded, Brixworth built,

the Book of Durrow and Durham A 11 10 illuminated. It is of the greatest

interest that, inNorthumbria and the other English kingdoms, furnished burial

also restarts in the later seventh century and continues into the early eighth

(Geake 1997, 124). It is furnishing of a very particular kind: necklaces and

ornaments of a marked Roman and Byzantine (rather than Frankish) character

are found predominantly in female graves. One burial with a pursefd of

sceattas at Garton-on-the-WoIds, is certainly as late as 720. By this time, plain

incised grave-markers were being erected at Whitby and Hartlepool, the

' - Lindisfarne Gospels with its virtuoso insuIar ornament had been completed at

Lindisfarne, at Jarrow Bede was writing his history and the immense Codex

Amiatinus with its meticulous adherence to Cassiodorus' classical prototrpe

had been lost on its way to Rome. Northumbria in the early eighth century

was not only a hive of creative endeavour; it was also a mass of alternative

expressions, the re-ified ideas of clerics and warriors, northerners and

southerners, men and women, those who live 011 the Wolds and those who

lived in the Vale of York or by the Tees, the Wear or the Tyne. The society W-%

presumably stable enough to allow differing opinions and the distribution of

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

1Class I stonels

't Eccles place-name

O long-'cist cemetery

if

R

square-barrow cemetery

St Ninians (Ecciesj

Fig. 1:5. The seventh-cenfuryargument in Fye. Map prepared by Inn Smikh

(Smith 1996, fig 2.5).

resources was generous enough to allow plural and varied expressionsin stone

and vellum.

In 710, Nechtan, King of the Picts, sent to Ceolfrid, abbot of Wearmouth/

Jarrow for advice on t h e expression of Christianity in the Northumbrian

manner: not just how to calculate the date of Easter, but the correct form of the

tonsure, and how to build a 'Roman' church (HE V.21). And yet the

consequences of his initiative seem to have resulted in no network of monastic

scripforin producing Pictish gospels and hagiographies. What they have left us

is something very different: scores of monumental slabs, "carrying Pictish

12

Marfin Carver .

syg-tb~lsas well as Chrishnmatifs that were famiiliar in the local repertoire

of Iona or mr&umbria.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that Canterbury, Jarrow, Iona, the Garton

burials, the Codex Amiafinus, the Lindisfarne Gospels, and the Class I1 Pictish

stones on Tayside actuallyrepresent different reactions to Christianization. Was

this because the peoples concerned were ethnically distinguished, or felt they

re? Angles, Britons, Scots and Picts spoke a different langiiage, Bede tells us,

so why should the language of their art and material investment not differ too?

Yet it seems stTange that a shared ideology should take so many different

forms between neighbours, and in the case of the Garton burials and the Codex

Amiatinus, the same linguistic group was presumably involved. Do the late

seventh- and early eighth-century burials proclaim an enclave of dissident

women, resentful of the Chstian project? Or are some women gqardbgtheir

family claims by imitating the imperial ornaments of Theodora, in order to

express aristocratic membership of a Roman 'folki, as opposed to the illiberal

clerical alliances of wjl&id?

On the supposition that material culture is meaningful, and that the style

of investment is deliberately chosen, we are entitled, I think, to read into it

differen~po&ic.a~s_tances.

There seems no good reason to allow these forrns of

expression to be simply local, cultural, vague, ill-informed, confused or

'syncretic' (Fletcher 1997, 126-153). That seems a negative way to view a

people who emerge from the pages of Bede as predatory, extravagant and

fiercely opinionated, just as IikeJy to express themseIves forcefully in words

and material culture as any other privileged class through the ages. Conversion

did not, it seems, produce a homogeneous culture for us to find, but appears

to have expressed itself in very different ways - differences here ascribed to

politics. How could such political stances be defined? The archaeoIogy has a

pattern to it, and the documents give us hints of inter-Clwistian dissent, so as

a first step we could set out to seek correlations between them.

DzfjCerent roods fo Christianify

Since we are concerned here with political signds within communities that

have adopted Christianity in some form, we should be searching for a model

that distinguishes between the different ekindsof Chstian organization and

economics, ~t least three varieties of Christian organization or socio-economic

control are 'well known and provide us with a starting point. In the episcopal

system, a bishop holds authority over a territory (the diocese) and draws

revenue from it. This is the system that most closely echoes Roman imperial

administration and requires a similar method of taxation to run it. The

archaeological correIate is the episcopal centre of which the finest example has

been given by Chades Bonnet's excavation of the episcopd group at Geneva

(1993). The attributes are the basilica, itself a type of Roman government

building, the baptistery and the pulpit. At Geneva, the baptistery, initially a

.

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

43

small tank, developed with the increasing demand until it acquired its own

supply of piped water. The trappings of an episcopd church, with its imperial

aura, can be contrasted with a materially more elusive but intellectually more

influential variant, the monastic church. Whatever the detailed circumstances

of early monasticism, it has the genera1 appearance of an autonomous

movement, if not exactly dissident then at least less a creature of state than the

hierarchy of bishops (Chitty 1977). whatever else drove the earliest eremitic

monks to the desert, an ec~nomicconsequence would be a freedom from tax

or m e . When the hermits clubbed together in the coenobitic communities, the

. seeking of independent non-taxabIe endowment would have been an early

method of survival, one which was later adopted in northern Europe. Colmba

received Iona from the Picts and King Oswald 'gave lands and endowments

to establish monasteries' including Lindisfarne (HE III.3) and Jarrow was

supported by lands on which Bede was born (HE, see autobjographical note,

p 336).

The Christianity practised by the monasteries of Egypt wouId not have

been organized and delivered in t h e same way as the imperial Christianity i t

Geneva or Hagia Sophia, and it seems highly likely that there was

confrontation. Such a confrontation has been postulated as endemic in the late

Roman town, where the 'episcopal group' is situated inside the official city and

grafted into the late Roman administration, while the 'monastic centre' grows

up in the extra-mural cemetery around the person of a martyr (Perinetti 1989),

Either or both these cenfxes may then act as a kernel for the growth of the

early medieval town, providing two nucleii which each presumably had its

declared and fiercely argued rationale. This phenonemon, which Perinetti

t e r n "bipolarity', can be seen at Aosta and Salona. At Geneva, the episcopal

centre within the walls wins the battle for hearts and minds and town lay-out,

while at Tours the monastery proved to have the greater magnetic force.

The archaeological correlates for northern monasteries earlier than the St

Gall plan in the 'ninth century are notoriously hard to define. The remains in

the Egyptian desert invite us to look for simple cells of hermits, perhaps

clustered together, a vision which has influenced the identification of Skellig

Michel and Tintagel as monasteries. There has long been an assumption that

early insular monasteries should be sited in an oval or circular or curviIinear

-.. - - the British Iun of Wales and Cornwall. Few of these have been

enclosure,

dated: at Whithorn, a ditch 10m Iong and lrn wide containing an undated

sherd of glass was extrapolated into a monastic boundary enclosing half a

hectare (Hill 1997,29,77). At Hoddom, the vallum and pallisade, traced on the

ground as a D-shaped enclosure, gave five radiocarbon dates in the seventh

century, prompting the excavator to suggest a date of construction between 600

and 680 (Lowe, in press). The sites of some documented Irish monasteries (for

n j found in association wkk circular bank~d

example that at ~ i l t i ~ m a are

enclosures (Mytum 1992,80); but in so far as they resembl; the prehistoric rdh,

they might represent the recycling of a local idea (Ryan and Mitchell 1998,

14

Martin Carver

260), while other forms of monastic enclosure, such as that at ~lonma-ise,

are apparently rectangular. The site of the present monastery, on Iona is

enclosed by a penannular bank, but this has lately yielded a prehistoric

radiocarbon date (Fisher 1996). The possibility must be considered that

monastic communities took whatever disused fort they were offered by the

king, as did Fursa when he moved into = h eredundant: Saxon Shore fort at

Burgh Castle, courtesy of King Sigebert of East Anglia (abbe).

.

h i d e the enclosures, we look for ways of distinguishing the monastic

from any other kind of estate centre in which there has been educated

investment at a high level. In the north, a number of the documented monastic

sites are signed by grave markers with simple crosses and inscriptions: for

example Jarrow, Monkwearmouth and Hartlepool, Whitby has 41 (Hawkes

1999) and Iona has numerous examples (Fisher 1996), although many of these

may have accrued during the lingering aftermath of the early Christian period.

Monasteries use and produce books, so that vellum p s ~ d ~ c or

~ ofinds

n of styli

ought to be d i a ~ o s t i c ,But accepting thdi.-"the middle Saxon aristocracy

provided leadershp both for those who fight and those who pray, it would not

be impossible for attributes of the literate sector to appear on a seigneurial

estate (see Loveluck, this volume). As we can so far see them, the markers of

monastic centres, while they kcho thos;! of a secular estate, at least differ from

those of episcopal centres. Since the peoples of Britain and.Ireland potentially

had access to the full range of Christian models, we are entitled to deduce that

such a difference had a meaning behind it and was deliberately chosen.

A people unused to taxation would find the endowment of monasteries

preferabIe to the imposition of a permanent revenue required to support

bishops. But another tendency has long been present in Christian practice, and

there seems good reason for supposing that it would have been an option as

early as the conversion period; it would moreover require far less of an

organizational upheaval in a pagan people. In this adoption of the Christian

structure, the faith is administered neither ,by bishops or monks, but directly

by the landowner or local aristocrat who can appoint and pay his own priest.

Such a 'secular' or 'private' option should be. signdled by individud a$

decentralized investment, so is bound to be harder to see. The most persuasive

examples are provided by those communities that erect monuments in

dispersed patterns - patterns which prompt an association with estates. The

$pression of se'cdarity is reinforced if the iconography is varied and features

everyday life, rather than being merely iconographic, repetitive add orthodox.

The Pictish Class II and the Anglo-Scandinavian monuments seem to be strong

candidates in this respect (Carver 1998~).

A less visible but equally telling example is offered by the small personal

funerar'y crosses found in central Europe, and recently studied by Miiller-Wille

(1998b; Fig 1.6). In fifth-to seventh-century Trentino, cross-shaped brooches

were deposited with females; in the central Rhine/Mosel area, cross-shaped

brooches of the late seventh century were also found in the graves of females;

'

The Politics elf Early Medieual Mon~amentality

Fig. 1.6. Distribution of sixth- l.o eighth-centek y gold foil crosses in the

Alamlrnnic urea between the Rkine and Danube (Muller-Wille

1998b,,fig 6).

while in the Alamannic district between M e and Danube, both sexes were

buried with gold foil crosses from the sixth to the eighth century. In each case,

the crdss was the main Christian signal. It is specificdly noted that in

Alamannia none; of the gold-foil crosses was found in connection with the

earliest churches; moreover this is not an imitation of an earlier Christian

practice, since no grave with a cross is known from the period from the first

to the fourth century in t$e Mediterranean. One reasonable interpretation of

this pattern is that the date and distribution of the burials accurately reflect the

progress of a gradual conversion northwards (ibid., fig 3); but without having

to challenge that general picture, it can be noted at least that the acceptance qf

Christianity was signalled in these territories in different ways. If the converted

landlords of the RhineIand repIaced their barrows with churches, and the

citizens of Geneva expanded and improved their massive episcopal centre, the

people of Namannia, sandwiched between them, induIged in the less

extravagant practice ofsewing small gold crosses on to the tunics of their dead.

Was h s modesty, poverty or ignorance? Or does the chosen signal represent

a non-centralized economy and a belief in maintaining authority at community

level - in short a different political stance?

16

,

M ~ r f i Carver

n

This case for a contiontation between Christian prescriptions depends on

the archaeological identification of their correlates and their distribution. But

some support can also be found in the sparse documentation, for'exam~leas

was revealed in Wilheh Levison's cIassic essay of 1946, which records

instances of tension between bishop and monastery and Christianized

aristocrats in the eighth century. Already in 672 the Hertford Canons state 'No

Bishop is to disturb a monastery or take its property by force' the implication

being thqt they might be tempted to do so {Levison 1946,231, while the Synod

of Cloveshoe in 747 was aimed at restoring 'the hierarchical order and a

regular church administration - provinces under an archbishop in direct

contact with Rome, dioceses with a monarckucal bishop supervised by the

archbishop and controlling the whole clergy of his district' (ibid. 86). The

Bishop was sacramentally necessary but their function was sometimes

exercised by 'wandering bishops and other bishops without dioceses but

attached to monasteries' (ibid. 97). Politically powerful converts preferring the

,secular option could apparently operate in a similar way. Cuthbert md seven

continental bishops of English origin sent a letter to King Ethelbald of Mercia

to admonish him and reprove him for his dissoIute life and his encroachments

on possessions and privileges of monasteries (ibid. 92) - a glimpse of an

alternative secuIar church which probably delivered more satisfactorily the

economic and politicd interests of the Mercian aristocracy. Levison

summarized the tendency of landowners to form their own 'proprietkry'

churches and monasteries (Eigenkirchen, Eigenklosfer) and reminds us that 'such

tendencies might be a source of danger to the monastic ideals' (ibid. 28). It is

clear that bishop, abbot and Iord had a discourse in which much was claimed

and definitions were blurred. It would have been in the interests of Bishops to

claim jurisdiction although they had none, and for landlords to acknowledge

Rome but to pay nothing and do nothing which would encourage Roman

control of their affairs. Wandering bishops would have been useful in

ordaining priests and giving them liturgical authoriiy and sacred powers, but

they would have brought no necessary allegiance to an archbishop or to the

whole Roman apparatus - of which the northern Europeans were (and still are)

endemically suspicious. We should expect ideological difference to be denied

in documents even while it was practised or proclaimed on the ground. This

suggests that the search for expressions of locd politicd resistance or

alignment through the study of monuments is a legitimate quest.

In Britain, perhaps the object of investment most sensitivd to the Iocal

Christian prescription is the standing stone monument, a field to which

Rosemary Cramp has made an immeasurable contribution. Lxke barrows, the

stone crosses may have started as memorials to an individual ancestor, whose

descendants continued to profess control of the same land. Like barrows, they

may have acted as places to meet and dispense justice. If family and power are

signalled in cross-slabs such as those from St Vigeans or Aberlemno roadside,

so are the elements of Christian doctrine; enough at least to merit the benefits

'

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality

17

of the Christian cornmercid network without sacrificing autonomy to either

king, bishop, abbot or pope. At a later date the cross might have been joined

by a church and this too might have been a local or private commission. If we

can make its socid label stick, the standing stone monument is going to be a

powerful tool with which to write history - because we have plenty of them

(see Edwards, this volume). A m a Ritchie (1995) has made the case that centres

such as Meigle produced monuments, especiaIly the widely distributed

standing cross-slabs, through lay patronage in the ninth and tenth centuries.

Such monuments, bearing a cross and other icons, were surely estate-markers

that reflected the taste and aspirations of the lahdlords, but also satisfied the

need for a ritual focus for a community accustomed to associate spiritual

orthodoxy with a local war-leader. George Henderson (1999, 209) observes:

'According to the Hodoeporicon or guide book, taken down from the verbal

report of St Willibdd, the English missionary who died as Bishop of Eichstadt

in Germany in 785, it was the custom on nobleman's estates to have the

stmdard of the holy cross set up as a focus for daily prayer ... The cross

monument was evidently a place of resort in time of crisis.'

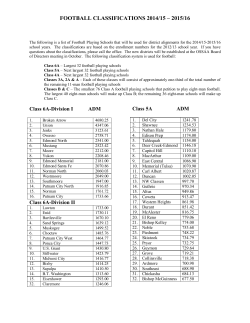

The newly-converted Vikings seem to have preferred the secular mode of

Christian conh.01 to the monastic or episcopal model (Fig. 1.7). Jim Lang's

survey of East Yorkshire (1991) showed that the grave-markers of the seventh

and eighth centuries were distributed among a handful of monastic sites, a

point reinforced by Jane Hawkes (1999, 405) with reference to northern

Northumbria: of 'approximately 230 pieces of carved stone associated with preViking contexts north of the Tees, nearly 180 come from just five sites:

Lindisfarne, Hartlepool, Hexham, Wearmouth and Jarrow'. But this distribution

changes radically in the ninth century. In East Yorkshire, the monuments are

more numerous and more dispersed, as well as displaying a more individual

iconog;aphy. It was Rosemary Cramp's observation, made many years ago

(1980, 18), that 'the Vdcings secularised art just as they secularised

landholding', that set me thinking (in the context of the politics of our own

day) that perhaps the Scandinavian hostility was not to Christianity but

towards state control, taxation and the alienation of land to non-wealth

creators. The Vikings, by ,dissolving the monastic system and substifmting a

secular alternative, had succeeded in effecting a conversion of their own

(Carver 1998~).

Conclusion

'

These case studies, briefly expounded, are held to imply that the episcopal, the

monastic and the secular church represented three different strategies for

developing a Christian kingdom which has shed paganism. Each mode of

religious control had very different implications for the people - especially the

aristocracy - in terms of self-determination, inheritance, prosperity and

alliance. A fly on the wall d a Dark Age hall must have heard the argument

18

Martin Carver

over and over again: loss of sovereignty and increased taxation is the penalty,

heaven and an expanded market the reward. A soft strategy for the king (who

had most to gain from the church's protection of his dynasty) was to endow

some of his own land and encourage others to do the same, in the hope of

qualifyng for the Christian alliance, while avoiding the alienation of his own

peerage. But some Ieaders would not be strong enough to achieve even this

compromise. Landowners resist an irreversible commitment to extreme and

dirigiste doctrines, preferring to cherish the northernerJs ancestral ethos: every

man his own lord, in control of his own land and with his own link to God.

But there would be no harm in adding Christ's escutcheon to one's shield,

especiaIly if it earned useful contacts and warded off the threat of a take-over

or conquest on trumped-up ideological grounds.

HOWlikely is this picture? Was the eighth-century inhabitant of Britain

really capable of such ingenious decision-making? How far does this model

superimpose on early Christianity the intellectual fragmentation of alI that has

happened since that time? Does it urge a particular version of Christianity to

which certain local politics of our own day inclines? William Frend (1996, 61)

uses the term 'confessional interests' to describe schoIarship driven by a

particular branch of Christian ideology, showing how loyalty to the success of

the Roman imperial past had inhibited the archaeoIogica1 recognition and

rediscovery of the Donatists. But Donatism was a Christian variant which most

certainly existed, was professed, debated, opposed, championed and expressed

in monuments. The native inhabitants of Numidia (now Libya) had under

Rome adopted a religion ruled by a sacrifice-hungry god ('SaturnJ) which

demanded human victims, In 260-290 'the religion of the great majority of the

Numidians swung irreversibly towards a biblically-inspired. form of

Christianity in which the blood-sacrifice of martyrdom replaced tf.-te bloodsacrifice to Saturn. This was central and southern Nurnidia, the heartIand of

the Donatist movement' (ibid. 118). On the ground Donatism was traced

through inscriptions which carried 'recognizably Donatist formulae' and by

association sculptural themes, such as martyrdom (ibid. 69, 231). For Frend

himself (1996,168), one of the duties of archaeology is to release some of those

alternative voices long suppressed by orthodoxy: 'Donatists, Montanists,

Manicheans and Coptic and Nubian Monophysites at last could begin to speak

for themelves through inscriptions, papyri and the steady accumulation of

material evidence'.

A number of Frend's great French North African predecessors had

asserted that the roots of Donatism lay in Berber (i.e. indigenous) nationalism.

A 'Iocal rebuilding' of the incoming doctrine happened again under Islam

when the Maghreb produced a number of sects culminating in that of the

Fatimids which was to spread far and wide. It is certainly tempting to see all

the monumental variations cited here as due to an endemic, indigenous

viewpoint. On this interpretation, the Scots, Picts, Northumbrians and Saxons

would not be expressing their differing politics, but adapting the incoming

The Polifics of Early Medieval Monumentality

Fig. 1.7. Distribution of sculpture in East Yorkshire (Lang 1992): a )

seventh to eighth centuries; b) ninth to eleventh centuries.

doctrines to an unchanging and inevitable individual preference. This is an

ethnically determinist argument which, instead of arguing for immigration of

new ethnic groups to explain cultural.change (e.g. the Anglo-Saxons) attributes

the change to the different reactions of permanently rooted native groups

occupying adjacent territories. For Northumbria at least, this could be

questioned: hers within a territory that extended from York to Lindisfarne,

were produced in the same decade the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Codex

Amiatinus and the Gartort-on-the-Wolds burids (above). This is an era of

experiment rather than adaptation.

Recent scholars have gone out of their way to diminish the differences

between any 'Celtic' church and others (Fletcher 1997, 92; BIair 1996, 6; Hair

and Sharpe 1992). My thesis is intended to bring into focus and interpret such

differences as we can find, and to suggest that behind them lay real conflict.

But it should be noted that I have attempted to explain these differences not

on ethnic or even ~ I t u r agrounds,

l

but on the basis of politics. I have nothing

to say about a 'Celtic' church either, only that during the seventh and eighth

centuries, some of those living in the west appear to have adopted a different

monumental programme to those living in the east, and that this must indicate

something. That something, in my view, would not be an incorrigible ethnicity

but a different way of thinking and a different approach to power. It wouId

probably be sensible at this stage to allow the possibility that deep-rooted local

culture might have an effect on whatever monumentality was practised. But

the facility of communication and awareness of pressure should have allowed

the big issues to be debated in a communal forum. With the variation of

political stance known from North Africa, we can hardly doubt that such

variations were also manifested in the north of Europe, both in the seventh

century and over the next 1,000 years.

References

Alexander, J. G. 1978. Insular Manuscripts, 6th to the 9th Century (A Survey of Manuscripts

illuminated in the British Isles), London: Harvey Wller

Bailey, R. N. 1992. Sutton Hoo and seventh-century art, in R. T. Fame11 and C. Neuman

de Vegvar (eds), SulEon EJoo:$f& years ~~fcer,

31-34, Oxford, Ohio: Miami University

Bede. Historiw Ecclesiastics Gentis Anglomm, B. Colgrave and R. Mynors (eds and trans),

Oxford: Clarendon Press

Blair, J. 1996. Churches in the early English landscape: soda1 and cultural contexts, in J.

Biair and C. Pyrah (eds), Church Archaeology: Research directions jbr the future ( C B A

Res Rep 104), 6-18, York: CBA

Blair, J. and Pyrah, C {eds) 1996. Church Archseology: Research directionsfor thefuture (CBA

Res b p 104), York: CBA

Blair, J. and Sharpe, R. (eds) 1992. Pastoral Care b@re the Parish, Leicester: Leicester

University Press

Bohme, H. W. 1993. Adelsgraber im Frankenreich. Arckologische Zeugrusse zur

Herausbildungeiner Herrenschichtunter dem merowingischenKonigen, Jahrbuchdes

Riirmisch-Gemnischen Zetmlmuseums Mainz, 40, 397534

The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentnlity

21

Bonnet, C. 1993. Les fouilles de I'mcien groupe ipiscopal de Gentve (2976-19931 {Caleers

dfarch6010gie gengvoise l), Geneva

Bradley, R. 1988. Time regained: the creation of continuity, J Brit ArchaeoE Assoc, 140,l-17

Bradley, R. 1993. AIterrng the Earth: the origins of monuments in Britain and continental

Europe: the Rhind Lectures, 1992-92, Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Carver, M. 0. H. 1986. Sutton Hoo in context, Settimane di SSfdio, 32, Spoleto: Centro

ftaliano di Studi sd1'Alt.o Medioevo, 77-123

Carver, M. 0. H. 1987. Santa Maria foris Portas at Caste1 Seprio: a famous church in a

new context, World Archaeologj, 18 (3), 312-29

Carver, M. 0. H. 1993. Arguments in Stone: Archaeological research and the European town in

thefirsf nrillennium AD, Oxford: Oxbow Books

Carver, M. 0. H. 1995. Boat burial in Britain: ancient custom or political signal?, in 0.

Crumlin-Pedersen (ed), The Ship as Symbol in Prehistoric and Medieval Scfindimvia,

111-24, Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark

Carver, M. 0. H. 1998(a). Sutton Hoo. Burial ground of Kings?, London: British Museum

Press

Carver, M. 0.H. 1998@).fherlegungen ziir Bedeutung angel-sachischer Grabhiigel, in

A. Wesse (ed), Studren ziir Archaologie des Ostseeraumes won der Eisenzeit zum

Mittelalter. Festschrfifffiir Michael Miiller-WiEle, 259-68, Neumiinster: Wachholtz

Carver, M. 0.H. 1998(c).Conversion and politics on the eastern seaboard of Britain: some

archaeological indicators, in B. E. Crawford (ed), Conversion and Christianity in the

North Sea World, 1140, St Andrews: University of St Andrews

Carver, M. 0. H. 1999{a). Review of Ian Stead, The Salisbuy Hoard, British Museum

Magazine, (Spring 1999), 39

Carver, M. 0. H. 1999@).Exploring, explaining, imagining: Anglo-Saxon archaeology

1998, in C. Karkov (ed), The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England: basic readings, 25-52,

New York and London: Garland

Carver, M. 0.H, in press. Burial as poeby: the case of Sutton Hoo, in E. Tyler (ed), AngloSaxon Treasure, York: Centre for Medieval Studies

Childe, V. G. 1929. The Danube in P~ehistoy,Oxford: Clarendon Press

Chitty, ,Q. J. 1977. The Desert a City: Egiitian and Palestinian monasticism under a Christian

empire

Cramp, R. J. 1980. The Viking image, in R. Farrdl (ed), The Vikings, 8 1 9 , London:

Plullimore ,

Fisher, I. 1996. The west of Scotland, in Blair and Pyrah, 3741

Fletcher, R. 1997. The Conversion of Europe, Berkeley: University of California Press

Frend, W. H. C, 1996. The Archeology of Early Christianihj. A history, London: Chapman

Foot, S. 1990. What was an early Anglo-Saxon monastery?, in J. Loades (ed), Monastic

Studies: the continuity of a tradition, 48-57, Bangor: Headstart History

Geake, H. 1997. f i e Use of Grnve Goods in Cornersion-period England c.600-c.850 ,(Brit

Archaeol Rep 261), Oxford: BAR

Hawkes, J. 1999. Statements in stone. Anglo-Saxon sculpture, Whitby and the

Christianization of the North, in C. Karkov (ed), The Archaeology of Anglo-Smon

England: basic readings, 403-21, New York and London: Garland

Henderson, G, 1999. Vision and Image in Early Christian England, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Hill, P. 1997. Whithorn and St Ninian: the excavation of a monastic town 1984-1991, Whithom

and Stroud: Whithorn Trust and Sutt-onPublishing

22

Marfin Carver

Hines, J. 1984. The Scandinavian Character of AngIian England in the Pre-Viking Period (Brit

Archaeol Rep 1241, Oxford: BAR

J o h n , S. 1983. Burgh Castle: Excavatrons by Charles Green 1958-61 (East AngIian Archaeol

Rep 20), Gressenhall: Norfolk Museum Service

Lang, 1. 1991. Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Sculpture, 3, York ~ n dYorkshire, Oxford: British

Academy / Oxford University Press

Levison, W. 1946. England and the°Continent in the Eighth Century, Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Lowe, C, forthcoming. Exmvntions at Hoddom, Dumfriesshire: An wlclosed holy place of the late

first lnilIennium AD, Edinburgh: Historic Scotland

Lutovsky, M. 1996. Between Sutton Hoo and Chemaya Mogla: barrows in eastern and

western early medieval Europe, Antiquity, 70, 6726

Mango, M. M,, Mango, C., Evans, A. and Hughes, M. 1989, A 6th century Mediterranean

bucket from Bromeswell parish, Suffolk, Antiquify, 63, 295-311

Mitchell, P. and Ryan, M. 1998. Reading the Irish Landscape, Dublin: Town House

Miiller-Wille, M. 1998(a). Zwei reliogiose Welten: Bestattungen der frankischen Konige

Childerich und Chlodwig, Abhmdlung dder Akadewaie dur Wissenschfien und der

Liternfur, Mainz: Steiner Verlag

Miiller-Wille, M. 2998(b). The Cross as a symbol of personal Christian belief in a changing

religious world. Examples from selected areas in Merovingian and Carolingian

Europe, KVHAA Konferenser 40, -179-200, Stockholm: KVHAA

Myturn, H. 1992. The Origins of Early Christian Ireland, London: RoutIedge

Opie, I. and Opie, P. 1977. The Lore and language of School Children, London: Granada

Perinetti, R. 1989. Augusta Praetoria. Le necropoIi christiane, Acfes du XI Coragres

Infernational d'archiologae Chritienne, 121526, Vatican City

Proudfoot, E. 1996. Excavations at the long-cist cemetery on the Hallow Hill, St Andrews,

Fife 1975-7, Pruc Soc Antiq Scot, 126,387-454

Proudfoot, E. 1998. The Hauowhill and the origins of Christianity in Scotland, in B. E.

Crawford (ed), Co~vmsionand Christianity in the North Sea World, 57-74, St Andrews:

University of St Andrews

Ramquist, P. H. 1992. Hiigom. The excavations 1949-1984, Urn&: University of Urn&

Ritchie, A. 1995. Meigle and lay patronage in the 9th and 10th centuries AD, Tayside and

Fife Archaeological Journal, 1, 1-10

Sharpe, R. (trans) 1995. Adomnnn of Iona. Life of St Columba, H ~ n d s w o r t h Penguin

:

Shephard, J. 1979. The social identity of the individual in isolated barrows and barrow

cemeteries in Anglo-Saxon England, in B. Burnham and J. Kingsbury (eds), Space,

Hierarchy nnd Society: interdisciplinay studies in social area analysis (Brit Archaeol Rep,

Int Ser, 59), 47-79, Oxford: BAR

Smith, I. 1996. The archaeology of the early Christian church in Scotland and Man AD

400-1200, in Blair and Pyrah, 19-37

Slupecki, L. P. 1997. Einfliisse des Christenhurts auf die heidnische Religion der

Ostseeslawen irn 8.-12. Jahrhundert: Tempel - Gottbilder - Kult, in M. Miiller-Wille

(ed), Rom und Byzanz im Norden. Mission und Glazdbenswechsel iwr Ostseeraurn wlihrend

des E-14. Jahrhzdnderts, 177-89, Manz: Akademie der Wissenschaften und der

Litera tur

Taylor, H. M. and Taylor, J. 1965. Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

van de Noort, R. 1993. The context of early medieval barrows in Western Europe,

Antiquity, 67, 66-73

© Copyright 2026