Good Will Come of This Evil - National Council of Teachers of English

CCC 61:1 / september 2009 Shevaun E. Watson “Good Will Come of This Evil”: Enslaved Teachers and the Transatlantic Politics of Early Black Literacy This essay offers an earlier chapter in the history of African American literacy by examining colonial literacy campaigns within the eighteenth-century Atlantic world. The discussion focuses on one such transatlantic effort spanning from London to Barbados, South Carolina, and West Africa, which used enslaved teachers as agents of literacy. T he Charles-Town Negro School, perhaps the most sustained effort in promoting slave literacy by a single organization in early America, provides a remarkable case for investigating an earlier chapter in the history of African American literacy. Opened in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1743, the school provided a rudimentary Christian education for hundreds of slaves and free blacks in the low country until it closed in 1764.1 The school was supported by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), the missionizing arm of the Church of England. Its purpose was to bring, through the printed word, Christian light to the “Pagan Darkness” of the colonies’ plantations as part of a “sound imperial policy” (Secker; emphasis mine). Of course, the SPG managed other slave missions in the American colonies, and CCC 61:1 / september 2009 W66 Copyright © 2009 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved. W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 66 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” other Christian organizations were also involved in early education efforts for blacks, not to mention that many individuals took it upon themselves to teach slaves or free blacks (e.g., Pinckney 34; see also Richards; Webber). The Charles-Town Negro School, however, is a particularly interesting site of black literacy in early America because it was part of a large-scale, intercontinental experiment in plantation pedagogy. Faced with little success in the first decades of its slave missions, the SPG began in the 1730s to articulate a new method of conversion that sought to meld literacy with Christian slave owning. Literacy was crucial for slaves’ salvation, and so, the Church argued, providing such instruction was among the masters’ highest Christian duties: “If it be said that no time can be spared from the daily labour of the Negroes to instruct them, this is in effect to say that no consideration of propagating the gospel of God, or saving the souls of men, is to make the least abatement from the temporal profit of the masters” (Gibson, “Letter 1” 25; see also “Address”). An important aspect of their experiment in Charleston actually involved the SPG itself in slave ownership: the Church purchased young male slaves to serve as catechists (lay schoolmasters) to teach their fellow slaves in the hopes that these boys could speed the language acquisition, and thereby the conversion, process.2 Though ultimately the SPG was unable to demonstrate the efficacy of this novel approach or to persuade slave owners that literacy and Christianity could complement slavery, and even though the Charles-Town School was regarded by some as a failed mission, a glimpse into this unique effort is valuable nonetheless for contemporary considerations of black literacy. The history of African American literacy is necessarily intertwined with the particularities of American slavery, with all of its various mechanisms of power and control. At times, slave codes impeded or altogether prohibited blacks’ access to the printed word. “Literacy,” as Henry Louis Gates explains, “stood as the ultimate parameter by which to measure the humanity of the authors struggling to define an African self in Western letters” (131). For the better part of the twentieth century, historians, sociologists, and folklorists, among others, traced the perils and possibilities of black literacy through the paths of households, hush harbors, slave narratives, white and black churches, established and informal schools, antislavery and abolitionist organizations, southern plantations, northern cities, early American print culture, colonial experiments, antebellum reforms, and postbellum promises (e.g., Du Bois; Woodson; Cornelius, Slave and “When”; Joyner, Down and “If You”). A new generation of historians has deepened our understanding of the circuitous paths W67 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 67 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 many ordinary blacks took to educate themselves during and after slavery (e.g., McHenry; Williams). Scholars in rhetoric and composition have put their own mark on this research as well, expounding upon the historical, theoretical, and pedagogical dimensions of African American reading and writing practices (e.g., Gilyard; Royster; Richardson). All together, this body of scholarship illustrates the myriad ways in which literacy functioned for enslaved and free blacks as a complex and contested site of liberation, self-determination, and collective action, as well as indoctrination, disillusionment, and “social death” (Fordham, Blacked and “ ‘Signithia’ ”). Some of the most useful understandings of literacy today, those that are versatile and “ecological” rather than deterministic, account for the fundamental ambivalence—what Frederick Douglass described as both a “blessing” and a “curse”—that reading and writing has historically entailed for blacks in this country. Though he “prized it highly,” Douglass considered literacy a cruel contradiction: “As I read . . . [t]hat very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish. . . . In moments of agony, I envied my fellow-slaves for their stupidity” (58, 61). This struggle with the vexed nature of literacy is an aspect of the history of black literacy that is perhaps too rarely pondered. Though Douglass is commonly used as a touchstone within explanatory frameworks of African American literacy that emphasize individual triumph and collective liberation, undercurrents of ambivalence and resistance can be traced back to a host of shortcomings and unintended consequences of literacy for Africans in colonial America. As Harvey Graff notes, the history of literacy “holds powerful lessons in disappointment and misplaced expectations” (Labyrinths 325). More than a century before Douglass penned his autobiography, some Africans at the Charles-Town Negro School “writhed under” (to use his words) the literacy efforts associated with colonial schemes for power of the Atlantic and its North American rim. My discussion of early black literacy through the lens of the SPG’s Negro School is organized around the intersections of literacy and colonization, specifically as they pertain to issues of race, slavery, and Christianizing campaigns throughout the eighteenth-century Atlantic world and the burgeoning black Diaspora. I focus in part on the two boys who were enslaved teachers at this school by considering their dual roles as slaves and (school) masters, as well as their difficult negotiations of Anglo-European literacy in their lives. Some of my work here is admittedly speculative given the lack of direct evidence about these individuals in the archives, but such speculation—or “critical imagina- W68 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 68 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” tion,” as Jacqueline Royster calls informed historical guesswork—is warranted when reconstructing the past from the silenced or neglected point of view. In doing so, I seek instead to elaborate some possible understandings of these boys’ unenviable fates, as well as some tenable connections to today that help illuminate a past about which we know very little. I rely upon some contemporary, critical approaches to literacy to help make sense of these slaves’ lives specifically and to understand the complicated nature of black literacy in colonial Atlantic America more generally. Brian Street’s work on “colonial literacy,” Harvey Graff ’s theories of the “literacy myth,” and John Ogbu’s analyses of “oppositional culture” among America’s “involuntary minorities” all offer useful ways to reconceptualize the ostensible failure of the Negro School. Much more than a curiosity of Anglican or South Carolina history, the Charles-Town School can be usefully understood in terms of the ideological work of schooled literacy within an imperial context. A colonial and transatlantic history of African literacy in America highlights meaningful connections between the coercive nature of the black Diaspora and oppositional responses to it that included, among other things, ambivalence, disengagement, and “unutterable anguish” in the face of misplaced expectations about the consequences of literacy. I want to offer two specific insights we might gain from this particular historical case. First, the Charles-Town School provides valuable evidence for how black literacy functioned before the nineteenth century. By 1845, twelve states had passed anti-literacy statutes or education restrictions on slaves and free blacks, the vast majority of which were enacted not in the 1700s but in the 1830s, which suggests that current estimates of black literacy in the eighteenth century may be too low (see Richards). Not only were there a variety of discreet ways for Africans to acquire Anglo-European literacy, but such efforts were in general less restricted before the Revolution than after, as racism was to become more tightly woven into America’s social, political, and legal fabric. The colonial era reveals no “better” or “worse” circumstances for blacks’ literacy acquisition, but a set of different relationships to and experiences with written texts. Second, an enterprise like the Negro School demands a more serious historical and theoretical engagement with the African Diaspora in relation to black literacies. As the educational anthropologist Signithia Fordham argues, drawing upon the work of John Ogbu, the opposition of some contemporary black students to mainstream education is “the Diasporic resistances of persistent peoples.” She explains that “displaced peoples are involuntary migrants who must reinvent themselves constantly, often from positions of systematic W69 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 69 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 subordination or threatened extinction (“ ‘Signithia’ ” 158). An important part of the history of African American literacy includes such “acts of persistence” in the face of Diasporic realities. Resistance to education among particular demographic groups in America can be understood by studies of past schools, students, and teachers, as well as current ones. The Transatlantic Mission of the SPG One of the key differences between colonial America and later eras, such as the antebellum and abolitionist periods that are more typically referenced in historical discussions of African American literacy, is the centrality of the Atlantic world in the orientations of blacks and whites alike. In the 1700s, the colonies were more closely identified with the Atlantic world than with any conception of “America.” As much recent scholarship in early American studies has illustrated, exclusively North American perspectives on the colonial era are no longer viable; instead, the Atlantic world functions as an “intercontinental unit of analysis,” especially for understanding slavery’s intricate mechanisms of power—some of which pertained directly to literacy (Piot 155; e.g., Gilroy; Linebaugh and Redicker; Carretta and Gould). Transatlantic connections of all kinds have shaped America throughout its history, but in the eighteenth century the transatlantic world dominated people’s identifications and networks, which then shifted slowly toward a national consciousness after the American Revolution. The campaigns of British organizations such as the SPG placed black literacy very early on within this cross-cultural context. With executive power located in the imperial center of London, and individual agents dispersed throughout the Atlantic, the SPG managed the slave missions as parts of a whole, regularly transporting ideas, materials, missionaries, and slaves from one location to another. The SPG provides an apt historical example of what Street calls “colonial literacy,” involving campaigns conducted across nation-states. “Members of an outside culture,” he explains, “introduced their particular form of literacy to a colonized people as part of a much wider process of domination,” including “the spread of their own religion and of the colonial administration to set up bureaucratic structures through which they could rule” (36). As early as 1660, Britain’s Council on Foreign Plantations was ordered by Charles II to devise viable ways “to invite Native Americans and African slaves to the Christian Faith” (qtd. in O’Connor 31).3 Hearing reports of the aggressive and even violent evangelizing tactics of the Spanish, the Church of England adopted different promotional strategies, ones embracing “the Gospel Spirit of Meekness and W70 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 70 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” Charity.” Instead of using brute force, the SPG vowed to employ “softer, milder ways”—the rhetorical force of reason and benevolence—to make Anglicanism seem like a better choice to “those barbarous People” (qtd. in O’Connor 32). An empire of converts attained through literacy, education, free will, and spiritual insight would be an emblem of the Church’s power, and such converts would help pave desirable political and economic paths throughout the Atlantic. When, to universal surprise, the SPG fell heir to two large Barbadian sugar plantations, the Church was presented with a rare opportunity to enact its particular brand of benevolent imperialism: to rule with compassion rather than fear; to care for slaves’ bodies, minds, and souls; and to gain an invaluable foothold in the West Indies that would enable the spread of Anglicanism alongside British colonialism. S-O-C-I-E-T-Y Spells Trouble: The SPG in Barbados The Church first became a slave-owning institution when one Christopher Codrington bequeathed a good deal of his Barbadian property to the SPG upon his death in 1701. The SPG planned to use the booming profits from the sugar trade to transform the Codrington plantations into harmonious and edifying Christian communities of literate and docile blacks. By 1711, the Society had formalized its plan to teach the Codrington slaves to read so that they might be converted and baptized, and further, for these plantations to become “a center for the Christianization of the American slaves” through the development of a “college” that would “breed up” missionaries to be sent abroad (Bennett, “S.P.G.” 191; emphasis mine). Bishop William Fleetwood seized upon this moment in his widely disseminated 1711 SPG annual sermon to castigate masters who would not allow Christian instruction: “These unhappy people” are endowed “with the same Faculties, and intellectual Powers; Bodies of the same Flesh and Blood, and Souls as certainly immortal. . . . Let any of the cruel Masters tell us, what part of all these Blessings were not intended for their unhappy Slaves by God . . . and yet not permit these slaves to be Instructed?” (qtd. in Pennington, “S.P.G.” 14–15). The “Force and Cruelty” exercised by many slaveholders, Fleetwood argued, directly hindered conversion efforts. The Society sought to cast their form of slave ownership as a civilized, effective, and replicable model for the Atlantic world, particularly the American colonies. “Success, it was hoped, would lead to improvement of slaves’ condition elsewhere, and to the spread of education” (Klingberg, “British” 453; see also Calam 50). Slavery and sugar turned out to be more vicious masters than the Church anticipated. The Codrington plantations perennially lost money, requiring W71 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 71 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 greater demands of the slaves. The Africans languished there, many dying each year from malnutrition, sickness, and disease. The Society found itself relying heavily on the slave trade to maintain the estates’ productivity. Most of the West Africans brought to Codrington practiced tribal forms of worship and showed no interest in Christianity, literacy, or the SPG. By 1726, not one slave had been converted or baptized, and the “college” there opened in 1745 and was long reserved for educating white children. The only “reading” and “writing” that seemed to involve slaves for a long time was the practice of branding. The letters S-O-C-I-E-T-Y were burned onto the chests or backs of all Codrington slaves until 1733, when the local catechist suggested that the Society might not want to continue to engage in “a thing voted to be done only by the severest Masters or to the worst of Slaves” (qtd. in Klingberg, “British” 464).4 For several decades, the bodies of the Codrington slaves advertised to the world the cruel irony of being owned by a Christian organization that touted beneficence. Moreover, these slaves physically represented the very impossibility of an Anglo-European literacy flourishing amid the fierce contradictions wrought by colonial ambitions. “By definition,” Street argues, colonial literacy is “transferred from a different culture, so that those receiving it will be more conscious of the nature and power of that culture than of the mere technical aspects of reading and writing” (30). The Africans at Codrington did not need any “technical” Anglo-literacy training to be able to decipher the letters S-O-C-I-E-T-Y: they read quite clearly “enslaved.” Plantation 101: Retooling the Experiment for the Mainland Colonies Despite the enormous difficulties at Codrington, the missionizing zeal of the SPG continued unabated, and interest in discovering a reliable method of plantation pedagogy only redoubled in the 1730s.5 Then Bishop of London, Edmund Gibson, reflected upon the difficulties of the white catechists at Codrington; he discerned that they could not make any inroads into the slave communities there. Gibson wondered if some of the slaves themselves could be trained and utilized as teachers: “At least some of them, who are more capable and more serious than the rest, might be easily instructed both in our Language and Religion, and then be made use of to convey Instruction to the rest” (“Letter 1” 21, 23). Moreover, he reasoned, “whatever Difficulties there may be in instructing those who are grown-up . . . Children, who are born and bred in our Plantations . . . may be easily trained up to our own Language” and teach others (23). The Bishop had hit upon a plan: using young slaves as lay teachers for their own W72 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 72 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” communities. It would not be put into place for another 15 years, but in this unexpected way, Codrington did inform the SPG’s transatlantic operations. In hopes of rekindling previously failed efforts in North America, Gibson appointed the shrewd and dogmatic Reverend Alexander Garden as commissary (local Church leader) of the Carolinas, Georgia, and the Bahamas in 1729. Feeling no small amount of pressure to increase significantly and rapidly the number of slave converts throughout the Carolina low country, Garden informed London of his plan in 1740, a blueprint for plantation pedagogy that clearly echoed Gibson’s: “Touching the most effectual Method for Instructing the Negro in the principles of our holy religion, as it has been a Matter of my long and Serious Attention, I shall now humbly offer my final sentiment upon it in these following Conclusions,” which included five points: 1) relinquishing the attempt to instruct the “whole Body of Slaves, of so many various Ages, Nations & Languages”; 2) focusing only on “Home-Born” slaves under ten years of age as prospective students; 3) recognizing the neglect of slave masters and the failure of “White Schoolmasters” to teach slaves; 4) shifting the work of instruction to “Negro Schoolmasters, Home-born, & equally Property as the other Slaves but educated for this Service and employed in it during their Lives”; and, finally, requesting private contributions from local planters to supplement the Society’s charity (Letters, Sept. 19, 1740). He asked the SPG to empower “Three or Four or more of the Clergy in this province” to purchase, on behalf of the Society, “Three, Four, or Five Male Slaves, not under the age of Twelve, not exceeding that of Sixteen Years,” and for these slaves to receive instruction at the Negro School for two years, and then for these slaves to be used as schoolmasters on plantations across the low country (Letters, Sept. 19, 1740). In other words, the Charles-Town Negro School was originally conceived as a teacher-training ground for blacks, in addition to serving as a school for slaves. Garden amended Gibson’s plan by perceiving that the SPG could foster a kind of grassroots appeal for slave education if the organization shifted its attention and resources to creating a cadre of well-trained black Anglican teachers (see Gibson, “Letter 1” and “Letter 2”; Humphreys 15). The approach was nothing if not pragmatic: using slaves to teach other slaves was one way for the SPG to circumvent the new prohibition against organized slave literacy campaigns (Garden, “Letter from the Rev. Alexander Garden”). In 1740, the Carolina Assembly passed a revised Negro Act, which incorporated some antiliteracy provisions to quell whites’ anxieties in the aftermath of the 1739 Stono Rebellion. The explicit curtailment of educational opportunities for slaves was a main feature of the new statutory framework. However, the law did not prohibit W73 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 73 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 catechetical instruction to slaves, and its restrictions were directed at writing rather than reading (Cooper and McCord 7: 413). Moreover, the 1740 statute was not assiduously enforced, especially compared to the anti-literacy measures that were codified later in the nineteenth century.6 With Garden’s plan, slaves could effectively function as Church proxies. Like other missions throughout the Atlantic, this literacy campaign needed to be nonthreatening to whites and, at the same time, successful in reaching as many slaves as possible. Young male slaves were the key: “As among us religious instruction usually descends from parents to children, so among them it must first ascend from children, or from young to old” (qtd. in Creel 75). The boys could appeal to the “child-like” intellects of the slaves, Garden reasoned, while maintaining the docility and pliability of youths. The explicit exclusion of female slaves from teaching or learning also contributed to the favorability of Garden’s educational plan. He understood that slaves could be taught to read “so long as it was done discreetly and caused no problems” (Garden, Letters, Sept. 19, 1740). Boys teaching fellow male slaves to read the Book of Common Prayer provided a discreet and politic form of literacy instruction. Further still, teacher training harnessed the appeal of blacks teaching other blacks: “These youths would be of signal benefit,” Garden believed, as “negroes would receive instruction from them with more facility than from white teachers” (Letters, May 6, 1740). Whether or not he was aware that slaves had always been teaching others through informal, clandestine methods, the Charles-Town School adopted slaves’ longtime practice of autodidacticism and communal education (Williams). Garden, like Gibson before him, was quick to recognize white missionaries’ inability to penetrate in any meaningful way the social network of the slaves: “They are as ‘twere, a Nation within a Nation,” Garden remarked in one letter. “They labour together and converse almost wholly among themselves.” He imagined that “a Sett or two of these children would gradually diffuse and increase into open Day . . . the blessed Light among them” (Letters, May 6, 1740). In October 1742, the Society agreed to back his plan, hopeful that “good [would] come of this evil,” that by realizing their full missionizing potential, the evils of slavery and of their own slaveholding practices could be mitigated.7 They authorized the purchase of “two Male Negro Children such as they shall be judged most proper for Instruction.” The committee reviewing Garden’s request added that they intended to “consider whether this Scheme may not be of use to the Society’s Plantations in Barbadoes [sic]” (Society). By 1741, “two Negro youths” in Barbados were being trained in preparation for a similar school to be W74 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 74 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” started at Codrington (Klingberg, “British” 472–73). The SPG continued working across geographical, political, and cultural sites, illustrating the way in which notions about early black literacy and plantation pedagogy were promulgated within an atmosphere of cross-fertilization and colonization. In January of the following year, Garden reported to Society headquarters that he had purchased two boys from the plantation of Barbadian emigrant Alexander Skene (Garden, Letters, April 9, 1742; Skene 93).9 Though Garden regretted that it took him so long to find boys “to our liking,” Harry, fourteen, and Andrew, fifteen, seemed promising, “both Baptized in their Infancy and [able to] say the Church Catechism.” The boys lived with Garden under his “Maintenance and Education without charge to the Society,” and within eight months, Harry proved to be “of excellent Genius, & can now read the New Testament.” Garden surmised that Harry would be ready to teach in about six more months (Letters, Sept. 24, 1742). Andrew, by comparison, seemed “of a somewhat slower Genius, but of a milder & better Temper . . . requir[ing] less Authority and Inspection over him.” Garden intended for one slave to teach at Charleston and for the other “to be employed in like manner in one or other of the best settled Country Parishes” under the care of the missionary there (Letters, Sept. 24, 1743). The commissary clearly imagined this scheme replicating itself throughout the province as quickly as schoolhouses could be built and slaves purchased and trained. In March 1743, Garden publicly announced in the local newspaper his plan for the Charleston school since the schoolmaster (Harry) was now “sufficiently qualified,” and with donations from local families, the school opened in September of that year (“Advertisements”; “Negro”). For a little over two decades, the slave boy Harry instructed between 20 and 40 students each year. After one year, Garden reported to London that the school “succeeds even beyond my first Hopes or Expectation,” with 60 slaves in regular attendance: “18 of whom read in the Testament well; 20 in the Psalter, and the rest were in the Spelling-Book” (Letters, Nov. 6, 1744). Eight months later, the school was expanding still, teaching 55 children during the day and 15 adults in the evening (Letters, March 15, 1744). Each of Garden’s reports describes the school’s accomplishments in the most sanguine terms: the school was “flourishing,” in a state of “continued prosperity,” “full of children,” and, a decade later, “going on with all desirable success,” turning out about 20 “Scholars” each year (Letters, April 23, 1745; see also Dec. 22, 1748; Nov. 20, 1751). Such regular reports were required by London authorities, but they were also part of Garden’s promotional effort to obtain much-needed books and materials from SPG headquarters. He even appealed to other missionaries and churchmen in W75 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 75 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 Carolina for donations, receiving at one time fifty copies of Thomas Wilson’s The Knowledge and Practice of Christianity Made Easy to the Meanest Capacities (1740), which Garden deemed to be “of the greatest Service” for the school (Van Horne 94–95). From all of the commissary’s accounts, the experiment with enslaved teachers seemed a viable model of effective plantation pedagogy. The Trouble with Harry and Andrew: Separation by Education However shrewd, the SPG’s experiment was also deeply flawed. Its logic was predicated on the infantilization of blacks, and it seriously overestimated slaves’ desire to do the work of the SPG. The Charles-Town School is not, as some have argued, a “monument to the [SPG’s] belief in the intelligence of the Negro and his equal rights to the benefits of religion and education” (Klingberg, Appraisal 102), but instead a highly fraught venture that succeeded at the expense of Harry and Andrew themselves. Being in positions of spiritual and intellectual leadership conceivably allowed them some rare measures of autonomy: Blacks quickly perceived that the slave mission[s] offered them an opportunity to create a small space in the oppressive conditions of slavery: to conduct their own meetings, to take advantage of the privileges of leadership, to seize chances for literacy, and to build the black community and the black church. . . . [They] provided a rationale for training and supporting black leaders. (Cornelius, Slave 3) Such outcomes or possibilities were clear by the 1840s and 1850s, but much less so a century earlier. Being “the onliest one who could read” within a slave community was not always enviable or beneficial (former slave qtd. in Cornelius, When 88). Harry and Andrew’s work was underwritten and overseen by an Anglo organization that wove itself into the sociopolitical fabric of the low country slave system as part of a transatlantic colonial scheme—a reality that surely circumscribed the boys’ roles in and out of the classroom. By slaves’ own accounts, plantation teachers were rarely, if ever, appointed by white authorities; instead, those of a certain “predilection” were identified and encouraged by fellow slaves to teach others: “In order that I might study the Bible,” recalled one former slave, “the other slaves on the place worked my [garden] patch for me [in the evening] so I [could] study the book and read it to them” (Cornelius, Slave 138–39; When 88; see also Williams). Slaves helped, and likely respected, those teachers who grew out of the black community itself. In other words, Harry and Andrew may have been acceptable instructors in the eyes of Garden and other whites, but the blacks likely perceived these boy-schoolmasters quite differently. W76 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 76 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” On eighteenth-century South Carolina plantations, as elsewhere at the time, literacy was often perceived as necessarily changing a person’s being, and thus transforming his or her relationship to others and the world. Some early slave narratives remark upon the sacred authority of the “talking book,” a view that permeated colonial slave communities (e.g., Equiano; see also Gates; Richards 366; Street 66–68). To the degree that they were perceived as somehow fundamentally different from others, literate slaves sometimes found themselves ironically divested of power, respect, and place in the slave quarters. Historian Richard Olwell discusses such examples of educated and Christianized slaves who were ostracized on colonial Carolina plantations. These slaves lived “in a cultural ‘no man’s land’” between their masters and fellow slaves, neither identifying with, nor welcomed by, either group: “if they could not go forward into the community of the ruling class,” Olwell notes, “it was equally impossible for them to return to where they had been” (129). This presents a severe case of “separation by education,” as Richard Hoggart describes the alienating experience of educational imperialism (Promises 65). Harry and Andrew’s struggle to conform to Christian doctrine and to share their knowledge of print most likely “earned them only rebuke from their masters and derision from many unconverted slaves” (Olwell 131). The SPG’s literacy campaign entailed just as much possibility for individual isolation as it did for black liberation. As Hoggart illustrated in his groundbreaking work, The Uses of Literacy, acculturation through schooling can ultimately thwart one’s ability to activate the transformative possibilities of education. Harry and Andrew probably experienced acute social isolation: once children within a familial plantation community, the boys were reared by Garden himself within an exacting Christian setting and were then expected to teach such “values” alongside literacy in the Negro School. Though none of the SPG reports indicates any problems with Harry, the slave teacher was rather suddenly deemed “maniacal” and “profligate” after twenty-one years of ostensibly loyal service and effective teaching. The local vestry, a governing body of lay church members, ordered in 1768 that “Harry, the Negroe that keeps the School at the parsonage (for Repeated Transgressions) be sent to the Work house, and to be put into the Mad house, there to be kept till orders from the Vestry take him out” (St. Philip’s). The “work house” was Charleston’s penitentiary for recalcitrant slaves; owners brought incorrigibles there to be whipped and “broken.” Conditions at the nearby insane asylum are much less clear, but they could not have been agreeable, and church records do not ever indicate Harry’s release (Magazine Street, n.p.). Harry’s confound- W77 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 77 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 ing and tragic fate provokes us to ponder the possible connections between Harry’s education, his bondage as a teacher, his sanity, and whites’ and blacks’ perceptions of his mental and social stability. Harry’s “profligacy” may be understood then as “a result of pressures accumulated during the quarter-century during which he lived a solitary life in the inhospitable terrain between cultural lines” demarcated by literacy (Olwell 130). All SPG agents needed to conform to a stringent set of “appropriate” behaviors, a mandate surely all the more important for a slave instructor like Harry. Teaching others to become “moral and religious beings fit for the business of life” required that schoolmasters “take especial care of their manner, both in and out of School . . . [a]nd that they do in their conversation show themselves examples of Piety and Virtue to their Scholars, and to all with whom they shall converse” (Pascoe 844–45). Within this context, any “transgression” could be easily perceived as immoral or reckless. It is certainly possible that decades of servitude in the SPG classroom drove Harry to what seemed like an unmanageable state. He might very well have lost his bearings, so to speak, becoming adrift from the social moorings that defined his community and his place within it. Resorting to madness—or as it was typically called, “outlandishness”—may be seen as an “act of persistence,” to use Fordham’s phrase. The “physical, spiritual, and political survival” of Diasporic peoples “required strategies both subtle and outrageous,” she argues: “Evasion and dissemblance to avert violation and avoid the tyranny of pain; creating and passing on alternative identities to those imposed by the master class . . . organizing to defy the well defended boundaries that hemmed us in” (158). “Profligacy” may have been Harry’s deliberate strategy to be released from the care of the parsonage, or it may have been the tragic result of being (over)educated, converted, and forever distanced from his fellow Africans. The boy’s “failure” could also pertain more directly to his colonized status. In the terms of Ogbu’s theories of racial disparities in educational achievement, Harry can be understood as part of an “involuntary minority,” descended from people who were brought to the United States against their will through slavery or conquest and are ad infinitum denied full assimilation into mainstream society (Ogbu; Ogbu and Simons). Ambivalence and resistance, particularly in response to schooling that promulgates and polices mainstream values, are two common coping mechanisms. Harry’s difficulty in managing dual roles and conflicting identifications within and outside of the Negro School may actually extend beyond simply his education, beyond his ability to read and understand both potential freedoms and systematic oppressions in his world—Douglass’s W78 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 78 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” “curse” of literacy—and relate to larger issues of the black Diaspora and colonialism. Ogbu’s minority typology suggests that schooling or literacy alone are not the reasons for social alienation and intellectual disengagement; rather, the social function and ideological aspects of education when paired with a certain historical status render an oppositional identity or frame of reference for dealing with whites’ exclusions (see Ogbu; emphasis mine). Like Harry’s ambivalence, that of Douglass, about being able to read and write, does not pertain so much to actual abilities, or even to particular insights gained, but to the ways in which literacy and schooling function for blacks as sites of the greatest tension wrought by their Diasporic status in America. This tension was also likely felt by the other slave teacher, Andrew, who seemed to negotiate it differently. While the school flourished under Harry’s tutelage, Andrew’s placement had become a problem. Another SPG minister in South Carolina, Reverend Guy, made several requests for Andrew’s services. Guy reported to London that the local vestry “express[ed] interest with respect to the Instruction of Negroes according to the Proposal of the Rev. Mr. Commissary Garden . . . [and] they do humbly desire that the other Negro Young man may be sent into this parish to instruct his Fellow Negroes and the Children in the same way” (Society; Garden, Letters, March 26, 1744). Garden, however, had his reservations about the boy: “tho an exceeding [sic] good natur’d and willing Creature, [he] yet proves of so weak an understanding that I’m afraid he will not be qualified to teach alone” (Garden, Letters, Nov. 6, 1744). Even with an extra period of instruction, and after trying Andrew as an assistant to Harry, Garden concluded that the boy needed to be sold. But SPG authorities had their larger, Atlantic project in mind, and in September 1746 ordered Garden to send Andrew to Codrington to revive instructional efforts there. For reasons not entirely clear, one month later, the SPG transferred power of attorney to Garden for the “Sale or Disposition of . . . one Negro known by the name of Andrew” (Society). Since the boy was a native Carolinian, it might well be the case that family members still residing on the nearby Skene plantation persuaded Garden not to send Andrew away to Barbados. In 1750, Garden informed SPG authorities that he had finally sold Andrew locally and that the profits were used to purchase more books and supplies for the school (Garden, Letters, Sept. 9, 1750). In light of Harry’s troubles, we might likewise consider that Andrew’s “weak-mindedness” points not to some deficiency but defiance: maybe he did not want to become “literate” in the colonial sense of things, let alone a teacher of others. It is by no means the case that slaves simply embraced any and all W79 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 79 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 opportunities for education; they did not need theories of critical pedagogy to tell them that schooled literacy entails some degree of indoctrination and assimilation. As one former low country slave put it, “If you ain’t got education, you’ve got to use your brain” (qtd. in Joyner 255). While it is widely noted that teaching slaves to read pushed against the limits of the slave system, it is equally true, though perhaps less obvious, that Anglo-European literacy pushed against the boundaries of slave communities as well. Andrew may have shared some slaves’ suspicion of or disinterest in Anglosponsored literacy. Might he have feigned stupidity? The slave boy may not have been “slow” at all, but in fact rather quick to recognize a way out of the classroom and a situation he loathed: pretend to be too dim-witted to learn, too obtuse to teach. Andrew could have easily witnessed scenes similar to one described by another SPG missionary in the low country of the eighteenth century: “Our Baptized Negroes . . . pray’d and read some part of their Bibles in the field and in their quarters, in the hearing of those who could not read; and took no notice of some profane men who laught [sic] at their Devotions” (qtd. in Olwell 131). While the white onlookers interpreted such ridicule as slaves’ envy of education, such ostracizing behavior can also be understood as a disavowal of that education. The colonial sensibility of the SPG agents, and of their entire literacy campaign, assumes a fundamental desire on the part of enslaved blacks and colonized groups for particular kinds of literacies that are tied to particular formations of power. It may be the case that a colonial sensibility continues today and entails this same assumption, occluding from our historical view individual rejections and collective “failures” of literacy. Despite all the reports of success, it is curious that this experiment in slave education was never attempted again elsewhere in the low country. In fact, when Harry was “released” from his duties in 1764, the school itself did not remain open: “As there were no other black, or coloured persons competent to take charge of the school, it was discontinued” (Dalcho 193). Though the Society had consented to replace Andrew with another slave boy, such efforts to “keep up the [slave] stock for the purpose of education” were not pursued with the same vigor that got the Charles-Town School up and running (McCrady 247). That no acceptable replacements could be found from among all the slaves taught over the course of two decades may point to another botched attempt by the SPG. The school’s closing seems inexplicable from the source materials. If the school’s end is to be considered a failure, such inefficacy or incompetence should not be attributed to the slave teachers or the students W80 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 80 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” themselves. Clearly, some significant literacy instruction took place for many years at the Negro School, and likely beyond its walls: Harry and Andrew, and unnamed others who undertook the teaching of slaves on their own, “should be regarded,” as historian Jeffrey Richards argues, “as early African American schoolmasters, literate and capable of pedagogical innovation beyond what whites could offer slaves” (362). From Carolina to Codrington to Cape Coast Within a larger, transatlantic context, the closing of the Charles-Town School may have been unfortunate, and likely symptomatic of the Anglicans’ overall inability to capture the hearts and minds of early Americans (thanks in part to the great success of Methodism and other evangelical denominations throughout North America), but it was by no means the disaster that Codrington was. The organization’s experiment with enslaved catechists continued to be a popular technique to help convert blacks around the Atlantic world into the early nineteenth century. With the success of the school in Charleston, the SPG pursued their plan for revamping slave education at Codrington without the services of Andrew. In June 1745, new catechists from London arrived in Barbados, “herald[ing] improvements” on the plantations there. The main teacher there, Joseph Bewsher, turned the instruction of the plantation children over to two boys, John Bull and Bacchus, whom he supervised. These “promising youngsters had been receiving special instruction since 1741,” and acting “on a suggestion of the Reverend Alexander Garden of South Carolina that Negroes could be brought to Christianity by educated men of their own race,” he felt confident that the boys were “ready to teach others” (qtd. in Bennett, Bondsmen 83–84). Bewsher even used the same schoolbook at Codrington as in Charleston since Garden praised the efficacy of Wilson’s catechetical text geared toward the conversion of slaves. With John Bull and Bacchus, whom we know nothing about, Bewsher pursued an ambitious literacy campaign, attempting “to teach reading to all of the slaves from four to seven years of age” (84). Bewsher, and the SPG at large it seems, took hope in Garden’s positive reports from Charleston, and whether they recognized it or not, the American colony became the model of black education and conversion for Codrington rather than the other way around. The 1750s and 1760s brought political turmoil for the SPG in America and Barbados alike. Attitudes toward the Church of England became increasingly hostile, in Charleston and elsewhere, as the American colonies moved toward revolution. In Barbados, W81 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 81 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 Figure 1. The transatlantic network of early black literacy. Source: Thomas T. Smiley,“Atlantic Ocean,” Smiley’s Atlas (1842). Adapted and used with permission from Cartography Associates David Rumsey Collection: <http://www.davidrumsey.com/index.html>. the reasons were different—the Society became enmeshed in fierce local and colonial politics, but the result was essentially the same: pulling out and relocating missionizing efforts elsewhere. W82 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 82 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” The SPG turned to Africa. A former missionary in New Jersey, Thomas Thompson asked the Society to send him to the “Coast of Guiney, [so] that I might go to make a Trial with the Natives, and see what Hopes there would be of introducing them to the Christian Religion” (qtd. in Glasson 333). Thompson arrived in Cape Coast, a central hub of the English slave trade and transatlantic commerce, in 1751. Here, more than any other missionizing site, the SPG was intricately connected to the slave trade and transatlantic networks as Africans and Europeans of all sorts crossed paths in the port town. Thompson’s situation in Africa was obviously different from his station in America, but the CharlesTown School remained influential in his and the SPG’s approach: if African catechists “were only to be had by way of Purchase,” London advised him, “be careful in choosing out the most promising ones” (qtd. in Glasson 340, fn 18). However, rather than instructing the boys himself in Cape Coast, Thompson sent them to England for their education and training, hoping it would tie them more closely to the Church and the British Crown. In 1754, three young African men—William Cudjo, Thomas Caboro, and Philip Quaque—arrived in England and were sent to a school in Islington. Only Quaque returned as a missionary to Cape Coast in 1765, the other two having died while abroad. He was ordained a minister and quickly began work within the “multi-national, multi-ethnic, and polyglot community” that characterized the Atlantic town (Glasson 367). As an African local, Quaque was better able to negotiate these social and political complexities than any white SPG agent, harkening back to why the SPG had begun to invest in “native” missionaries in the first place. However, Quaque lived in a liminal position shot through with ambivalence about language, culture, and religion. Similar to how Harry and Andrew struggled to finesse their multiple identifications and conflicting roles in the Charles-Town Negro School, Quaque’s kinship ties and local connections actually hindered rather than helped his missionizing efforts in Africa. This was a paradox the SPG did not anticipate or ever truly understand. Indeed, the contradiction of using enslaved and black teachers to missionize within societies organized around race-based slavery presented a fundamental contradiction that the Society never could reconcile. Rethinking Early Black Literacy The aspects of the history of African American literacy discussed here point to broader contexts and contingencies that need to be reckoned with, a web of transatlantic figures and forces circumscribing nearly every aspect of black literacy in the Carolina low country for several decades of the mid-eighteenth W83 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 83 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 century. Garden was a colonial agent, Carolina planters were Atlantic exiles and emigrants, and, perhaps most important, Harry and Andrew and the other slaves were members of the African Diaspora whose sensibilities and worldviews were Atlantic rather than national. As Alan Rice argues in Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic, “Such people carried their culture in their heads, which meant that even in America, Africa was part of their existence” (24). As critics of the “Black Atlantic” and others have made clear, transatlanticism itself as a theoretical or historical construct does not necessarily negate a preoccupation with America, but it does offer a useful way to reframe things. “The creation of different black cultures on all sides of the Atlantic seaboard is pivotally dependent on marine rather than land-based exigencies, on cultural exchange rather than national homogeneity and the ideologies that flow from a controlling nation-state” (Rice 202). Situating African American literacy within the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, rather than an American one, is not only more historically accurate, but it also puts pressure on teleological and romanticized understandings of the power of literacy for blacks in this country. A transatlantic perspective disrupts heroic narratives of literacy acquisition as well as tropes of American exceptionalism by reminding us that black literacy has deep ties to the imperial networks and colonial economies of the African Diaspora. If literacy is ideologically correlated with economic productivity, political stability, participatory democracy, urbanization, modernization, and “civilization,” such relationships pertain most powerfully to, and such myths are promulgated most aggressively within, the Western world and the United States specifically, as Graff, Street, and others have argued. The case of the Charles-Town School provides some caution against elevating individual abilities above historical realities, or using such stories of “American” triumph to suggest that education can always improve upon or rectify a past wrong. This portrait enriches current discussions and debates about race, literacy, and schooling by offering an important historical correlate to some of today’s most vexing problems. This is not to overstate similarities between colonial and twenty-first-century America, but to demonstrate that the history of African American literacy extends much further back than commonly recognized and that past examples of blacks’ ambivalence or resistance to Anglo-European literacy can illuminate a different (i.e., colonial) context that still has bearing on today. Varied conceptions of African American literacy, both contemporary and historical, play a central role in efforts to recalibrate simplistic assumptions about the “consequences” of literacy. The lives of the enslaved teachers at the W84 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 84 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” Charles-Town Negro School portray a history of black literacy in the United States that is never simply “good” or “evil” but always syncretic and multivalent. Acknowledgment I would like to thank my research assistant, Jamie Boyle, who contributed a great deal of time and intellectual energy to this project. Her tenacity in the archives yielded valuable information, and our conversations helped me gain new insight. Joshua Call also assisted with research. I am indebted to the many staff members who offered their assistance at the repositories that hold the materials used here: South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina Rare Books and Special Collections, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, and South Carolina Historical Society. I also received various forms of financial and intellectual support from the Department of English at the University of South Carolina; I am enormously grateful for my colleagues there. Finally, I would like to thank the CCC reviewers whose suggestions helped me to improve this article immensely. Notes 1. Charleston was pronounced and written “Charles Town” (and variations thereof) until its incorporation in 1783. I use the historical spelling here to refer to the name of the school but the modern spelling for the city itself. The “low country” is a specific cultural area encompassing South Carolina’s lower coastal plain, running about two hundred miles north from the Georgia border. 2. For more on the SPG’s slave-owning practices and views toward slavery, see Glasson. 3. The work of the SPG among the American Indians, especially in the Northeast, is addressed by Brooks; Wyss. For more on the SPG’s work with Indians in South Carolina, see Bolton. 4. In 2006, the Church formally apologized for its involvement in the slave trade, especially as it pertained to Codrington Plantation (“Church”). 5. I’ve adapted the phrase “Plantation 101” from Hesse’s 2005 CCCC Chair’s Address: “The term [‘abolitionist movement’ to refer to ending the first-year composition requirement] is hyperbolic, promising the end of enslavement for both students and teachers, trading the tile to the plantation of English 101 for different intellectual spaces.” 6. See Cornelius (Slave Missions and “When”) on slave literacy; Finkelman on slave statutes; Williams on slave education; Egerton on connections between literacy and slave rebellions. 7. The phrase “good will come of this evil” is taken from the 1766 SPG annual sermon W85 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 85 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 by Bishop William Warburton. Though this sermon postdates the Charles-Town Negro School, the logic of Warburton’s sentiment about the slave-owning practices of the SPG existed long before 1766 and continued to be reiterated for several decades after. See Klingberg, “British” (462) and Introduction. 8. Alexander Skene was among the many white Barbadian planters dispossessed of land when the island’s sugar production was consolidated into massive plantations like Codrington, and many of these farmers like Skene immigrated to South Carolina at the beginning of the eighteenth century. As early as 1713, Skene was among a handful of South Carolina planters openly educating slaves or allowing them to be instructed by SPG missionaries (Pascoe 15), so it is not surprising that he is the South Carolina planter who sells two of his young slave boys to Garden. 9. Source: Thomas T. Smiley, “Atlantic Ocean,” Smiley’s Atlas (1842). Adapted and used with permission from Cartography Associates David Rumsey Collection: <http://www.davidrumsey.com/index.html>. Works Cited Bennett, J. Harry, Jr. Bondsmen and Bishops: Slavery and Apprenticeship on the Codrington Plantations of Barbados, 1710–1838. 1958. Rpt. Millwood, NY: Kraus, 1980. . “The S.P.G. and Barbadian Politics, 1710–1720.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 20.2 (1951): 190–206. Bolton, S. Charles. Southern Anglicanism: The Church of England in Colonial South Carolina. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982. Brooks, Joanna, ed. The Collected Works of Samson Occom, Mohegan: Leadership and Literature in Eighteenth-Century Native America. New York: Oxford UP, 2006. Calam, John. Parsons and Pedagogues: The S.P.G. Adventure in American Education. New York: Columbia UP, 1971. Carretta, Vincent, and Philip Gould, ed. Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. “Church Apologises for Slave Trade.” BBC News 8 Feb 2006. 25 Feb 2008 <http:// news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/ uk/4694896.stm>. Cooper, Thomas, and David J. McCord, eds. The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. 10 vols. Columbia, SC: A. S. Johnston, 1836–1841. Cornelius, Janet Duitsman. Slave Missions and the Black Church in the Antebellum South. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 1998. . “When I Can Read My Title Clear”: Literacy Slavery, and Religion in the Antebellum South. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 1991. Creel, Margaret Washington. “A Peculiar People”: Slave Religion and CommunityCulture among the Gullahs. New York: New York UP, 1988. Dalcho, Frederick. An Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in SouthCarolina. Charleston, SC: E. Thayer, 1820. Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, W86 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 86 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. New York: Oxford UP, 1988. Written by Himself. 1845. Rpt. Ed. David W. Blight. Boston: Bedford, 1993. Du Bois, W. E. B. The Education of Black People: Ten Critiques, 1906–1960. Ed. Herbert Aptheker. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1973. Gibson, Edmund. “An Address to Serious Christians.” 1727. Rpt. Humphreys 16–20. Egerton, Douglas R. Rebels, Reformers and Revolutionaries: Collected Essays and Second Thoughts. New York: Routledge, 2002. . “Letter 1: The Bishop of London’s Letter to the Masters and Mistresses of Families in the English Plantations Abroad.” 1727. Rpt. Humphreys 21–31. Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. 1789. Rpt. Classic Slave Narratives. Ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. New York: Penguin, 1987. . “Letter 2: The Bishop of London’s Letter to the Missionaries in the English Plantations.” 1727. Rpt. Humphreys 32–34. Finkelman, Paul, ed. Race, Law, and American History, 1700–1990. The AfricanAmerican Experience. 11 vols. New York: Garland, 1992. Fordham, Signithia. Blacked Out: Dilemmas of Race, Identity and Success at Capital High. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996. Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993. Gilyard, Keith. “African American Contributions to Composition Studies.” College Composition and Communication 50.4 (1999): 626–44. Garden, Alexander. “Advertisements.” South Carolina Gazette 14 Mar 1742: n.p. Glasson, Travis F. “Missionaries, Slavery, and Race: The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World.” Diss. Columbia U, 2005. ProQuest Digital Dissertations. ProQuest. U of South Carolina, Columbia. 28 Sep. 2007 <http://www.proquest.com/> . “Letter from the Rev. Alexander Garden.” 1742–43. Rpt. New-England Historical and Genealogical Register and Antiquarian Journal 24 (1870): 117–18. Graff, Harvey J. The Labyrinths of Literacy: Reflections on Literacy Past and Present. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1995. . “‘Signithia, You Can Do Better Than That’: John Ogbu (and Me) and the Nine Lives Peoples.” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 35.1 (2004): 149–61. . Letters to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. SPG Minutes, microfilm, reels 4–5. South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina. SPG Transcripts, Series B, vol. 4, 5, 9–15, 19–20. Microfilm, South Carolina Department of Archives and History. . “Negro School-House at CharlesTown Accompt [sic].” South Carolina Gazette 2 Apr. 1744. . The Literacy Myth: Literacy and Social Structure in the Nineteenth-Century City. New York: Academic P, 1979. Hesse, Douglas. “Who Owns Writing?” Conference on College Composition and Communication. San Francisco Convention Center, San Francisco. 17 Mar. 2005. Chair’s Address. Hoggart, Richard. Promises to Keep: Thoughts in Old Age. London: Continuum, 2005. W87 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 87 9/14/09 5:34 PM CCC 61:1 / september 2009 . The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working Class Life. London: Chatto and Windus, 1957. Humphreys, David. An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, from its Foundation to the Year 1728. 1730. Rpt. New York: Arno P, 1969. Joyner, Charles W. Down by the Riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1986. . “‘If You Ain’t Got Education’: Slave Language and Slave Thought in Antebellum Charleston.” Intellectual Life in Antebellum Charleston. Ed. Michael O’Brien and David Moltke-Hansen. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1986. 255–278. . “British Humanitarianism at Codrington.” Journal of Negro History 23.4 (1938): 451–86. . Introduction. Codrington Chronicle: An Experiment in Anglican Altruism on a Barbados Plantation, 1710–1834. 1949. Rpt. Millwood, NY: Kraus, 1974. 3–12. Linebaugh, Peter, and Marcus Rediker. The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. London: Verso, 2000. Magazine Street vertical file (#30-01) South Carolina Historical Society. McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2002. Ogbu, John U., ed. Minority Status, Oppositional Culture, and Schooling. New York: Routledge, 2008. Ogbu, John U., and Herbert D. Simons. “Voluntary and Involuntary Minorities: A Cultural-Ecological Theory of School Performance with Some Implications for Education.” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 29.2 (1998): 155–88. Olwell, Richard. Masters, Slaves, and Subjects: The Culture of Power in the South Carolina Low Country, 1740-1790. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1998. Pascoe, C. F. Two Hundred Years of the S.P.G.: An Historical Account of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, 1701–1900. London: Published at the Society’s Office, 1901. Klingberg, Frank J. An Appraisal of the Negro in South Carolina: A Study in Americanization. Philadelphia, Porcupine P, 1975. McCrady, Edward. The History of South Carolina under the Royal Government, 1719–1776. New York: Macmillan, 1899. O’Connor, Daniel, et al. Three Centuries of Mission: The United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, 1701–2000. London: Continuum, 2000. Pennington, Edgar Legare. “The Reverend Alexander Garden.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 3.2 (1934): 111–19. . “The S.P.G. Anniversary Sermons, 1702–1783.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 20.1 (1951): 10–43. Pinckney, Elise, ed. The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 1997. Piot, Charles. “Atlantic Aporias.” South Atlantic Quarterly 100.1 (2001): 155–70. Rice, Alan. Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic. New York: Continuum, 2003. Richards, Jeffrey H. “Samuel Davies and the Transatlantic Campaign for Slave Literacy in Virginia.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 111.4 (2003): 333–78. W88 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 88 9/14/09 5:34 PM wat s o n / “ g o o d w i l l co m e o f t h i s e v i l” ment of Archives and History, Columbia, SC. Richardson, Elaine. African American Literacies. New York: Routledge, 2003. Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change among African American Women. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1994. Street, Brian V. Social Literacies: Critical Approaches to Literacy Development, Ethnography and Education. New York: Longman, 1995. Secker, Thomas. “Sermon VI: Preached before the Incorporated Society of the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts; at the Anniversary Meeting in the Parish-Church of St. Mary-Le-Bow, on Friday, February 20, 1740–1.” Rpt. Fourteen Sermons Preached on Several Occasions. 2nd ed. London: Francis and Rivington, 1771. 110–47. Van Horne, John C., ed. Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery: The American Correspondence of the Associates of Dr. Bray, 1717–1777. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1985. Skene, Alexander. Property inventory. 25 Nov. 1741. South Carolina Inventories, vols. 41-431. Microfilm, South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Williams, Heather Andrea. Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2005. Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Transcripts. Miscellaneous South Carolina Papers, 1715–1833. Microfilm, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC. Woodson, Carter G. The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. 1919. Rpt. New York: Arno Press, 1968. Webber, Thomas L. Deep Like the Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community, 1831–1865. New York: Norton, 1978. St. Philip’s Parish Vestry Minutes. 17 Mar. 1768. Microfilm, South Carolina Depart- Wyss, Hilary E. Writing Indians: Literacy, Christianity, and Native Community in Early America. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2000. Shevaun E. Watson Shevaun E. Watson is an assistant professor of English and the director of composition at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire. She is completing her manuscript on African American rhetoric before 1830, entitled Coming to Terms: Toward a Cultural History of Black Rhetorics in Early America. Her work has appeared in Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Rhetorica, Early American Literature, Composition Studies, Writing Center Journal, and several recent edited collections. W89 W66-89-Sept09CCC.indd 89 9/14/09 5:34 PM

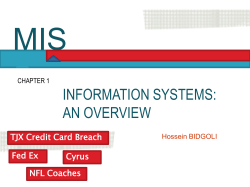

© Copyright 2026