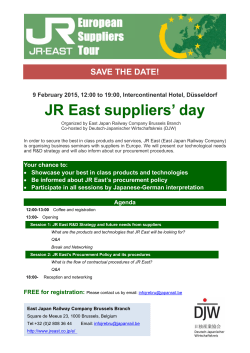

2015 Public Sector Supply chain management