LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE

LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research V-9001 G. L. Van Hoosier, Jr., DVM R. F. DiGiacomo, DVM Department of Comparative Medicine School of Medicine University of Washington Seattle, Washington The Laboratory Animal Medicine and Science - Series II has been developed by the following committee for the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine (ACLAM): C. W. McPherson, D.V.M., Chair; J. E. Harkness, D.V.M.; J. F. Harwell, Jr., D.V.M.; J. M. Linn, D.V.M.; A. F. Moreland, D.V.M. G. L. Van Hoosier, Jr., D.V.M.; L. Dahm, M.S. Portions of the project have been funded by a grant from the National Agricultural Library. Laboratory Animal Medicine and Science - Series II is produced by the Health Sciences Center for Educational Resources University of Washington. 2 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II University of Washington Health Sciences Center for Educational Resources Box 357161, Seattle, WA 98195 -7161 206/685-1156 ISBN: 1-55910-039-7 Copyright © 2000 by the University of Washington Health Sciences Center for Educational Resources and the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine All rights reserved. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 3 PRIMARY AUDIENCE Investigators, research technicians, and biomedical science students. GOALS The program presents sources and scope of laws and guidelines pertaining to use of rabbits, the historical uses of rabbits in research and testing, development of alternatives, attributes of rabbits as research animals, recognition of pain and disease, and signs and significance of common diseases. . OBJECTIVES When you complete this program on the use of hamsters in research, you should be able to: 1. State three sources of laws and guidelines pertaining to the care and use of rabbits for research, testing, or teaching. 2. List several noninfectious diseases that are studied using a rabbit model. 3. List several infectious diseases that are studied using a rabbit model. 4. Describe two or more traditional uses for rabbits in testing that are being replaced by alternative methods. 5. Discuss unique characteristics of rabbits that may justify selection of the rabbit rather than a rodent as an animal model. 6. List several behavioral and physiological signs of pain or distress in rabbits. 7. State two methods of euthanatizing rabbits that are approved by the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia. 8. List signs of disease in rabbits that should be reported to veterinary services for assessment and/or care. 9. Discuss the relevance of subclinical infections to research outcomes. 4 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II 1. Series Laboratory Animal Medicine and Science - Series II 2. Title Rabbits: Introduction to Use in Research 3. Objectives Upon completion of this program, you will know the major sources of laws and guidelines controlling the use of rabbits in research, testing, and teaching; the primary uses of rabbits in the past; several examples of alternatives; and the attributes of rabbits that may be useful in meeting research goals. You will also know how to recognize pain and distress in rabbits, how to euthanatize them humanely, and how to recognize signs of common diseases of rabbits maintained within a laboratory setting. 4. Legislation and Guidelines The use of rabbits for research, testing, or teaching is covered under the Animal Welfare Act, as amended by the Improved Standards for Laboratory Animals Act (Public Law 99-198) in 1985, and by the Public Health Service Act, which was amended by the Health Research Extension Act (Public Law 99-158) in 1985. 5. Scope In general, these laws cover the responsibilities of institutions and individuals using animals, such as training requirements and oversight of research by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC); and many aspects of humane care, identification, shipping, record keeping, caging and environment, surgical conditions and postsurgical care, requirements for use of anesthetics and analgesics, and methods of euthanasia. 6. The Guide A publication you should be very familiar with is the Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 1985 revision. The Guide provides a summary of principles and issues of humane use of laboratory animals for research, testing, and teaching. In addition, your institution may be controlled by State and local regulations, or may have institutional policies that you should be familiar with. HISTORICAL USES 7. List of historical uses The cause and treatment of many human diseases have been studied using the rabbit as a model. Because of its response to different diets, the rabbit was the first animal model used to study atherosclerosis. Other noninfectious diseases studied in the rabbit include osteoarthritis, pregnancy toxemia, endometrial adenocarcinoma, drug teratogenesis, hydrocephalus, muscular dystrophy, glomerulonephritis, and gallstones. 8. List (cont.) Infectious diseases studied in the rabbit include staphylococcal infection, bacterial endocarditis, and Reiter's polyarthritis syndrome. Hereditary studies include familial hypercholesterolemia, dwarfism, spina bifida, and glaucoma. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 9. 5 Syphilis - darkfield There are some diseases of man for which only the rabbit can serve as a model. One of these is syphilis. The rabbit is the only other mammal in which syphilis occurs naturally. The causative agent of human syphilis, Treponema pallidium, cannot be grown in vitro. 10. Syphilis But we can put the human organism into rabbits and study its growth there. If and when a vaccine is developed for human syphilis, trials will undoubtedly be conducted using the rabbit first. 11. Pet vaccination Animals have also benefited from research using rabbits. Pasteur developed a vaccine to protect dogs from rabies by using dried spinal cord from rabbits that had been experimentally infected. ALTERNATIVES 12. Alternatives We do not advocate using rabbits, or any other animal, solely on the basis of historical precedent. As science and technology have evolved, new options have become available. The increasing costs of using animals and societal attitudes toward their use have provided incentives for industry to be very active in the development of alternatives that reduce the numbers of animals used, use lower species, and refine techniques to eliminate potential discomfort in animals used. For example, ... 6 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II 13. Example - Current pregnancy testing ...until recently the most common pregnancy test used rabbits, and an animal was sacrificed for each test. Now pregnancy testing can be done by adding radioisotope-labeled antibodies to measure human chronic gonadotropin (hCG) levels in samples taken from the patient. Computers provide rapid and accurate data analysis. 14. Example - chemilluminometric immunoassay Another method of measuring hCG levels for pregnancy testing is chemilluminometric immunoassay procedure that uses monoclonal antibodies from a mouse and a solid phase reagent containing polyclonal antibodies from a goat. Although these procedures are still dependent on the use of animals, substantially fewer animals are needed. 15. Example - pyrogen testing Similar progress has been made in pyrogen testing. Traditionally, rabbits have been to monitor parenteral drugs and solutions for the presence of contaminating endotoxins. In 1976, Levine and Bang made a serendipitous observation that endotoxins caused horseshoe crab blood (amebocytes) to coagulate -- an observation that led to the development and commercialization of the limulus amebocyte lysate assay (LAL). The LAL is now in wide use for detection of endotoxins in a variety of settings, although the FDA still views the rabbit pyrogen assay as the definitive assay for many parenteral compounds. This may change, however, with refinement and supplementation of the LAL. 16. Example - Draize test Perhaps the most controversial use of rabbits has been in vivo cytotoxicity studies using the Draize test, which measures response to potential irritants by instilling a test compound onto a rabbit's cornea. The techniques used for the Draize test are being refined to reduce both the severity of irritation and the number of animals used. In addition, in vitro alternatives are at the stage of validation or early use. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 7 17. Example - cytotoxicity One of these is a visual morphological cytotoxicity assay combined with a assay quantitative neutral red spectrophotometric test, which shows good agreement with in vivo data. The neutral red assay first used cultured mammalian cells. Later it was adapted to also use fish cells as bio-indicators of aquatic pollution. 18. Example - antibody production The most frequent use of rabbits in experimental biology and medicine probably for production of antibodies. Until quite recently antibody production often involved repeated use of Freund's Complete Adjuvant (FCA), which was associated with adverse reactions. Now if Freund's is used, the complete adjuvant is given only for the initial injection, with incomplete adjuvant given for subsequent inoculations. Injections into the footpad are no longer accepted, with only intramuscular or subcutaneous routes recommended. There are also other alternative adjuvants that are commercially available. ATTRIBUTES OF RABBITS AS RESEARCH ANIMALS 19. Justification Considering our current socio-legal environment, it has become very important for an investigator to be able to justify use of a particular animal species; e.g., the species selected must correspond with the research or teaching objectives and the research must produce meaningful outcomes that cannot be obtained by using another method or a lower species. The following are attributes of rabbits that may justify their selection. 20. Size Rabbits may be preferred over other common laboratory animals because of their size. They have sufficient blood volume to allow for large blood samples to be taken either singly or serially. Because of their size, they may be preferred over rodents for studies that require temperature monitoring or surgical procedures. 8 21. Inbred strains LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II When we think of inbred strains, rodents may come to mind first. But the rabbit is highly desirable for studies that require larger animal and also an inbred strain. It is probably the largest laboratory species in which inbred strains are commonly available, and is often chosen for genetic studies. Multiple litters. The rabbit is one of the largest laboratory species to produce multiple litters per year. A rabbit can produce 6 or more litters a year, with a typical litter size of 7 or 8. Availability. Rabbits are readily available and relatively inexpensive when compared with species of similar size. Also, specific-pathogenfree (SPF) rabbits are available. This means that the breeder will supply animals that are free of Pasteurella and other infectious agents. 22. Disposition / handling Rabbits are generally docile animals that are easy to handle. They are, however, capable of inflicting serious injuries by scratching or kicking, and of seriously injuring themselves if they are frightened. A rabbit should be handled only by persons trained in proper methods of handling and restraint. 23. Caging / care Another attribute is that they are relatively easy to maintain and have no special requirements. An adult rabbit requires a smaller cage area than cats or dogs, they produce less waste, and they have no special requirements such as exercise or psychological enrichment, making them easier to maintain than other larger species. 24. Analogous systems Four other characteristics of rabbits make them desirable for specific research tasks. First, by analogous systems, we mean that some of the rabbit's organ systems are very similar to systems in man. The rabbit is often the model of choice to study immune responses for this reason. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 9 25. Embryonic susceptibility The placental barrier of the doe is hemochorial, similar to the human placental barrier; and rabbit embryos are extremely susceptible to both embryotoxic and teratogenic agents. Therefore, the rabbit is the model of choice for testing any product that might be used by pregnant women. 10 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II 26. Reproductive anatomy A doe has two uteri, each of which opens into the vagina through a separate cervix. This unique reproductive anatomy allows for an experimental group and a control group within a single biologic host. Rabbits are also useful for studies that require precise timing during gestation, as a doe ovulates about ten hours after mating, and gestation is well defined at 3032 days. 27. Susceptibility to disease The last of these characteristics that make the rabbit valuable for specialized studies is its susceptibility to spontaneous and induced diseases; such as syphilis, herpetic conjunctivitis, tumors associated with papilloma viruses, glaucoma, hyperlipidemia, and nutritional muscular dystrophy. A more complete list of spontaneous and artificially induced diseases of rabbits is provided in the Guide that accompanies this program. PAIN AND DISTRESS 28. Signs of distress One of the earliest signs of pain or distress in a rabbit is often anorexia, which may be accompanied by abnormal (hunched) posture or unwillingness to move. Other behavior changes associated with pain or distress are unexpected aggressions and, in extreme cases, vocalizations. Physiological signs such as elevated temperature and increased respiration rate confirm pain or distress. 29. Form for quantitative assessment A quantitative assessment of pain can be generated by assigning a point value to five considerations: body weight, appearance, behaviors, clinical signs, and response to stimuli. The form shown here is included in the printed materials accompanying this program. A high score in any individual category or a moderate score in several categories is an indication of probable pain or distress. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 11 30. Euthanasia Methods of euthanasia that comply with the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia's recommendations for rabbits include CO2 asphyxiation or intravenous pentobarbital (120 mg/kg of body weight). 12 31. LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II SIGNS OF DISEASE 32. Rhinitis In rabbits cold-like signs, or rhinitis, require immediate veterinary assessment, as they often are a manifestation of Pasteurellosis, commonly called "snuffles." The rabbit may have yellowish discharge around the nares, or matted hair on its forepaws from wiping the nose. 33. Head tilt Head tilt is another sign of Pasteurellosis. It results when an ear infection extends to the inner ear. 34. Diarrhea Acute diarrhea is a sign of several serious diseases of rabbits. The attending veterinarian should be notified, and isolation from the remainder of the colony may be indicated. Often the etiology remains undetermined, and a very high mortality rate occurs in affected rabbits. 35. Patchy hair loss V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 13 Patchy areas of hair loss, sometimes with dry, crusty skin lesions, may be a sign of ringworm. They frequently occur on the head, as shown here. This is a condition that should be diagnosed and treated, as ringworm is transmissible to people who handle the animal as well as to other animals. 36. Ear mite infestation Otoacariasis, or ear mite infestation, must not be ignored. The condition causes significant discomfort and stress to the affected animal, and may make access to the ear veins of the rabbit impossible. 37. Summary of signs 38. Other signs So far, we have discussed the significance of reporting and treating snuffles, head tilt, diarrhea, hair loss, and ear mites. Other signs of disease or discomfort that should be reported to veterinary services are... Failure to move about freely Failure to eat; weight loss Cloudy or red eyes Rough hair coat Ulcerative lesions, swellings Bloody discharge 39. Effects of disease The effects of disease on research are complex. Treatment of rabbits with antibiotics carries a high risk, as the alteration of gastrointestinal microflora can precipitate life-threatening diarrhea. Even conservative interventions such as isolation may generate stress and disturb the homeostatic balance of the animals. In addition to the potential loss of animals, the effects of disease include loss of time, increased costs, and possible compromise of data. 40. Subclinical infections Subclinical and persistent infections can also seriously distort research outcomes. Here are two examples: Assume you have set up a nutrition study in which the experimental group is fed a diet that is deficient in a particular element while the control group is fed a normal diet. You plan to measure the impact of the deficient diet by recording weights and you anticipate that the deficient diet will result in weight loss. 14 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II 41. Example Now, let's assume that many of the animals in both groups have a subclinical infection and that you are not aware of it because there are no apparent signs of disease. The additional stress of the deficient diet may be sufficient to trigger a clinical manifestation of the disease in the experimental group. Your experimental group may go off feed and lose weight, not as a direct result of the variable you were studying, but because of the combination of the subclinical disease plus the stress of the research. 42. Subclinical infections The second example shows how subclinical viral and parasitic infections affect research outcomes by modifying the immune responses in rabbits. In this study, a natural infection of rabbits with Encephalitozoon cuniculi produced varied immune responses, with depressed immunoglobulin G values. 43. Investigator When the rabbit is the model of choice, the investigator should make efforts to acquire disease-free animals from good stock, and the animals should be observed daily for signs of disease. 44. Programs This program has presented an introduction to the use of the rabbit for research, testing, or teaching. Additional programs in this series cover care and management; biology that is relevant to the use of rabbits in research and testing; and diagnosis and management of common diseases of rabbits. V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 15 45. ACLAM Credits The Laboratory Animal Medicine and Science - Series II has been developed under the following committee for the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine C. W. McPherson, DVM, Chair J. E. Harkness, DVM J. F. Harwell, Jr., DVM J. M. Linn, DVM A. F. Moreland, DVM G. L. Van Hoosier, Jr., DVM L. Dahm, MS. Portions of the project have been funded by a grant from the National Agricultural Library. 46. HSCER Credits Produced by the Health Sciences Center for Educational Resources, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195 2000 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank the following for images contributed to the program: E. Borenfreund, DVM S. Lukehart, Ph.D. 16 LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II APPENDIX 1 Examples of Medical Conditions in Rabbits and Corresponding Human Diseases Rabbit Human Hereditary: achondroplasia spina bifida glaucoma osteopetrosis Pelger-Huet anomaly hypogonadia diaphragmatic hernia lysozyme deficiency von Willebrand's disease C6-complement deficiency hyperlipidemia hypercholesterolemia epilepsy dwarfism spina bifida glaucoma osteopetrosis Pelger-Huet anomaly hypogonadia diaphragmatic hernia biologic role of lysozyme von Willebrand's disease C6 deficiency familial hyperlipidemia type III familial hypercholesterolemia epilepsy Shope fibroma Shope papilloma treponemal infection poxvirus-induced neoplasia papovirus-induced neoplasia syphilis arteriosclerosis atherosclerosis hypocalcemia toxemia of pregnancy endometrial adenocarcinoma arteriosclerosis atherosclerosis lactation hypocalcemia toxemia of pregnancy endometrial adenocarcinoma Infectious: Other: Artificially-induced conditions Rabbit Human Noninfectious conditions: vitamin A deficiency hydrocephaly hydrocephalus nutritional muscular dystrophy muscular dystrophy thyroiditis thyroiditis nephrosclerosis arteriolar nephrosclerosis synovitis synovitis degenerative joint disease osteoarthritis membranous /proliferative pneumonitis Interstitial pneumonitis cholelithiasis gallstones endotoxin-induced DIC DIC in endotoxemia Infectious conditions: staphylococcal infection bacterial endocardititis chlamydial arthritis chronic staphylococcal infection bacterial endocardititis Reiter's syndrome V-9001 RABBITS: Introduction to Use in Research 17 APPENDIX 2 QUANTITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF PAIN INDEPENDENT VARIABLE SCORE BODY WEIGHT 0 Normal 1 < 10% weight loss 2 10 - 15% weight loss, eating 3 >20% weight loss, not eating APPEARANCE 0 Normal 1 Lack of grooming 2 Coat rough, possible nasoculo discharge 3 Coat very rough, abnormal posture, pupils enlarged CLINICAL SIGNS 0 1 2 3 Normal Small change of potential significance Temperature Rise 1-2 , 30% rise of respiratory/heart rates Temperature change > 2 , 25% rise in respiratory/heart rates (or markedly reduced/shallow) UNPROVOKED BEHAVIOR 0 Normal 1 Minor changes 2 Abnormal behavior, less mobile, less alert, inactive when activity expected 3 Unsolicited vocalization, extreme self-mutilation BEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO EXTERNAL STIMULI (PALPATION OF INJECTION SITES) 0 1 2 3 Normal Minor exaggerated response Moderate abnormal response Violent response TOTAL SCORE 18 NOTES LABORATORY ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SCIENCE - SERIES II

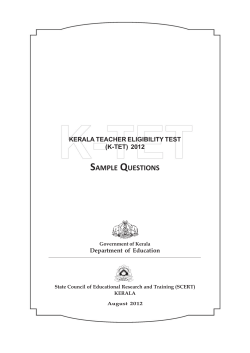

© Copyright 2026