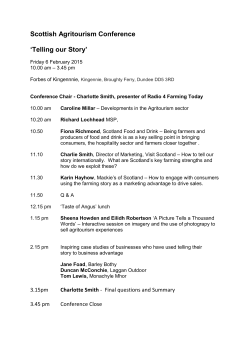

The ring pull and what to do with them.

The ring pull and what to do with them. In 1959 Ermal Cleon Fraze (from Dayton, Ohio) invented the familiar integral rivet and pulltab version, which had a ring attached at the rivet for pulling, and which would come off completely to be tossed aside. He received U.S. patent No. 3,349,949 for his pull-top can design in 1963 and sold his invention to Alcoa and Pittsburgh Brewing Company. It was first introduced on Iron City beer cans by the Pittsburgh Brewing Company. The first soft drinks to be sold in all-aluminium cans were R.C. Cola and Diet-Rite Cola (both made by the Royal Crown Cola company), in 1964. The original pull tabs were actually can tops where the tabs came off in the user's hand, which allowed people to make curtains out of them by hooking the popped off tabs to one another to make a chain. Enough chains side-by-side made a curtain. Now there’s an idea for the beach detectorists that find loads These pull tabs were a common form of litter — and a lingering hazard for bare feet, especially at public beaches. Also, some people dropped the tab into the can after opening it, rather than finding a wastebasket in which to throw the tab away. They then drank the beverage directly from the can, occasionally swallowing the sharp-edged aluminium tab by accident. So what can you do with them ....well here are some ideas. Think of the brownie points you will get if you make these for the good lady. Ring pull dress Ring pull clutch bag Ring pull belt Ring pull handbag Ring pull chair Lincolnshire trip 2015 By Shug Every year myself, Bill and Rob head down to Lincolnshire with one thing in mind to bring back as many goodies as we can from our detecting holiday. In the last few years its been getting harder and harder to get good finds as the farmers down there are now using modern methods of farming like spreading green waste on their farms and not ploughing their fields but just drilling the surface and planting another crop. This might be a good way to farm for the farmer as its saving him a fortune on chemicals and machining but for us detectorists it’s a nightmare. For example one field that we have in Lincolnshire is a great roman field with 300 years of habitation and a couple of roman villas that used to be on it and in days gone by you could walk onto the field and pull up roman coin after roman coin, brooches and even roman gold. The only signal you got was a good one and it always used to be something for the finds tin. A couple of years ago the farmer put some so called green waste on the fields and changed them completely. Now when you detect them you are getting a signal to dig every couple of steps you walk. Nowadays it tends to be silver paper, metal slag or computer circuit board fragments. You would think that with all this going on that out finds rate would disappear but strangely it hasn't . We are still finding good stuff and on this particular trip, all in all, we had 10 hammered coins, numerous romans including a pre BC roman denarius, roman fibulas, roman ring and even a gold hammered found by Bill. Not a bad haul for two and a half days! Why are we getting all this if our good fields are not producing like they used to? The reason is clear we are working the other fields we have that didn't produce harder and are getting amazing results. For example every one of us pulled up a hammered farthing or halfpenny . These farthings are so small they are a nightmare to find and even the best machines struggle to get them. The henry 8th that I pulled out took me a good few minutes to pinpoint it as its so small in the soil heap I had just dug out. We also are in the process of hunting out another farm in another area. This farm has produced a couple of good items but with 2000 acres its going to take time to find out the hotspots. We spent a whole day sussing out new fields with hardly any finds. The difference with these farms is every now and again there's a small roman comes up which keeps you focussed. We spent the whole second morning there trying to suss out fields to no avail but we can mark these ones of the map now only 1750 acres to go. The third day we headed to our Saxon fields that has produced good finds but is a massive field on a hill and only gives us its treasure up sporadically. We have had Saxon brooches and a Saxon coin as well as the odd roman coin but it’s a very quiet field again. Stewart our farmer pulled up a lovely steelyard weight from this field with unusual markings. The farmer that organises this trip brings along sausage rolls and cakes and tea and coffee for us to have for our lunch but this time he forgot our cups for the coffee. Never fear the thrifty scots are here and we improvised by making cups from some plastic water bottles that we had in the car. I ended up with the top of the bottle and it looked like a wineglass we had a good laugh about it after but at least we got our drinks. The only finds we had for the full morning on that field was sore legs and one roman coin. The last afternoon was spent back along at the first days fields for a couple of hours to see if we night pull of another hammered coin in the last hours. That night was the closing meal that our farmer Stewart’s wife Judith makes that was outstanding as usual . So after being disappointed with some of our fields it ended up being a great trip with great company and great finds. What more could a detectorist want! Now whens the next one. Oh well back to the Victorian pennies. Update on the seal found at Detecting Scotland dig 100 Boarshill, St Andrews The vesica seal found at this charity dig by Abbey Moffat was given the “Find of the day.” Little did the finder or anyone else know that day just how significant this find was to turn out to be. The seal is in fact the seal of the Bishop of St Andrews BISHOP WILLIAM LAMBERTON Early career William Lamberton began his career as one of the staff of priests in Glasgow Cathedral when Robert Wishart was bishop. He was appointed to one of the main offices of the cathedral (the office of chancellor), and attended King John Balliol’s first parliament in February 1293. After Edward I’s conquest of Scotland in 1296 he was one of more than 1,600 who swore loyalty to Edward. Wallace’s bishop Throughout his career William Lamberton had particularly close links with France. After the English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge on 11 September 1297 he was probably with William Fraser, bishop of St Andrews, in France trying to gain support for Scottish independence. When William Fraser died shortly afterwards, Lamberton was chosen on 3 November to be his successor as bishop of St Andrews. The decision to appoint Lamberton as bishop must have been approved by Wallace. He was consecrated bishop at the papal court in June 1298. Lamberton as Guardian After Wallace resigned as Guardian following the Battle of Falkirk on 22 July 1298, John ‘the Red’ Comyn and Robert Bruce (the future king) became joint Guardians. But they were bitter rivals. In 1299 Lamberton joined them as Principal Guardian when Bruce and Comyn fell out. He continued until 1301, when the exiled King John Balliol appointed John Soules as sole Guardian. Lamberton spent much of the following years on diplomatic missions for the independent Scottish government. He could not, though, prevent the King of France from making peace with Edward I in May 1303. This left the Scots to face Edward on their own. On 9 February 1304 most Scottish leaders surrendered to Edward I. Lamberton was still abroad, but was included in the surrender, and returned to Scotland soon afterwards. Lamberton and the inauguration of Robert Bruce In 1305 Lamberton was trusted by Edward I to lead Edward’s council in Scotland. Lamberton did not, however, think the cause of independence was lost. In June 1304 he had entered into a secret agreement with Robert the Bruce, who was by then head of the Bruce family and had his sights set on taking the throne. When Bruce made his move, Lamberton was ready to perform his role as bishop of St Andrews in Bruce’s inauguration as king in March 1306. The early years of Bruce’s reign Lamberton was captured by the English soon afterwards and was kept in chains for nearly a year, paying a huge sum for his release. Returning to Scotland in 1309, Lamberton’s skill as a diplomat allowed him to keep on good terms with both Edward II and Robert Bruce. In early 1312 he finally joined Bruce and abandoned Edward II for good. In 1318 the official opening of St Andrews Cathedral was performed as a celebration of Scotland’s liberation. (The cathedral had taken more than 150 years to complete!). This must have been the high point of Lamberton’s career. Lamberton’s last years Lamberton was so closely allied to Bruce that he was targeted along with Robert Bruce when in 1319 the pope, spurred on by Edward II of England, denounced Bruce and his supporters. Edward tried to get the pope to replace Lamberton with an Englishman as bishop of St Andrews. Lamberton defied the pope by repeatedly ignoring orders to come to Rome to answer for his actions. After the pope received the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320 the situation began to improve. Lamberton died on 20 May 1328, just over a fortnight after Scottish independence had finally been recognised when the Treaty of Edinburgh was ratified by the English parliament at Northampton on 4 May 1328. Bishop William Lamberton built a residential palace near the River Keny on the outskirts of Boarhills where the seal was found. It was known as the Palace of Inchmurtach, David Ist held a parliament in it after the bishop had died. SEAL INSCRIPTION + S' WILL'I de LAM'TO(N) EPI SCI AN(D)RE WHICH IS AN ABBREVIATED FORM OF + SIGILLVM WILLELMI LAMBERTON EPISCO SANCTI ANDRAE WHICH TRANSLATES TO + SEAL OF WILLIAM LAMBERTON BISHOP OF SAINT ANDREWS From buried treasure to hidden gem One of the beauties of metal detecting is that you just never know what journey a find might take you on. I would like to share one such journey that started from, perhaps, one of the best finds of my detecting career to date, and ended with an appreciation of why we must continue to preserve and share our history. The story of The Knights Templar is one that most of you will no doubt be familiar with and I was fortunate enough to find a Templar mount, which is now with the National Museum of Scotland. Whilst much has been written of their involvement in early medieval history and the subsequent legends, which range from the Holy Grail and the Ark of the Covenant to their association with Freemasonry, what is known of the Templars in Scotland? I thought it might be interesting to see what I could find out. Rosslyn Chapel outside Edinburgh has had a long held connection with the Templars, intricate carvings on the interior of the chapel are said by some, to have secret encoded messages and indeed it has featured prominently in several books and on film. Yet this is not the only place in Scotland to hold ties with the Templars. About 6 miles south east of Rosslyn Chapel as the crow flies, lies one such place; the village of Temple. Its name gives an indication of what may have gone before, however it was not known as temple until the 17th century, for the previous 500 years the area had been known as Balantrodach. Balantrodach (Stead of the Warrior) was the name of the area in which the main Temple Parish was situated. In the year 1128 a Knight Templar by the name of Hughes de Payen visited Scotland and was granted a meeting with King David I of Scotland. The King subsequently granted the Knights Templar the Chapelrie and Manor of Balantrodach. Balantrodach became their principal Templar seat and Preceptory in Scotland until the suppression of the order between 1307 and 1312. In 1307 the Knights Templar were arrested in France on false charges. Many modern stories claim that when King Philip IV had many Templars simultaneously arrested on October 13, 1307, that this started the legend of unlucky Friday the 13th. Following this, in 1309, the Templars in Scotland were told to come forward and face trial. Only two Knights turned up, Walter de Clifton and William de Middleton, the others could not be found. It is believed that they may have joined up with Robert the Bruce and, as legend would have it, played a crucial role in the defeat of Edward II at the battle of Bannockburn. None the less, at the end of the trial in Scotland they were found not guilty, meanwhile in 1314, the Templars in France were burned at the stake. Following this the orders went out that all Templars property was to be handed over to the Knights of St. John the Hospitallers. It appears that the Knights Templar disappear following their dissolution, although there are references to The Order of St John and the Temple who appear to continue until the reformation in the 1550’s. This however did not stop talk of the Templars. Indeed a local legend states that there is treasure to be found. It is alleged that the treasure of the Knights Templar was removed secretly from Paris, to be hidden in Temple and it goes on to state: 'Twixt the oak and the elm tree/You will find buried the millions free.' Of course as with any legend, how much of this is true or created by vivid imaginations remains anyone’s guess. However, French legends about the Templar treasure apparently also state that the treasure was taken to Scotland, with the knights landing on the Isle of May which would be the first island they would encounter in the Firth of Forth. Geographically, this would take them to the mouth of the river Esk, which could take them on to Temple or indeed Rosslyn. Despite my search for the Templars having come to a close, the history in the area continues. In 1571 the land was bought by George Dundas, from the Crown, for the benefit of his youngest son, and here began the next branch of my journey, which would not only take me back before the time of the Templars, but right up to the present day. Whilst metal detecting we are often lucky enough to touch history. Whether that be something 100, 700, or for those fortunate ones thousands of years old, there is always that thought of who and why. Certainly the Templar mount that I was lucky enough to find was around 800 years old. I am sure some of you reading will have ventured into your families past. I for one managed to get back to the early 18th century and have some books and artefacts that have survived from then. Now imagine you were able to go back, beyond the 18th century, 16th, even 13th century and could still trace your family. Not only that but be able to tell stories of daring deeds, royal encounters and political intrigue from the past. I was fortunate enough to meet one such person who has a great passion for, and an incredible knowledge of their family, and who was also kind enough to spend some time relating these to me, for you to enjoy. Hidden in the Midlothian countryside, not far from the historic village of Temple (so named because it it’s association in the 13th century with the Knights Templar) lies Arniston House. Sitting amongst tranquil woods and rolling parkland its impressive Georgian façade greeted me as I pull up outside. I was met by Althea Dundas-Bekker who, together with her daughter Henrietta manage and tend to the day to running of the house and its ongoing restoration. Althea was to be my guide for this morning, and who better to guide me round than a member of the family that has owned it since 1571. Whilst the family arrived at Arniston in 1571, the story of the Dundas family stretches way beyond that. The family can be traced back to the time of William the Conqueror, when Gospatric, son of Maldred (himself being of royal blood with his mother being the grand-daughter of King Ethelred) obtained the Earldom of Northumberland. He was however, in 1072, exiled to Scotland. Over the course of time and perhaps through a gift from King Malcolm or acquired by his descendants, land on the south shores of the Forth were the lands of Dundas, or the hills of the fallow deer. How many deer still reside there is debatable as these lands are now the site of the soon to be new Forth crossing. These early years involved associations with many famous names in Scottish history. Hugh de Dundas fought alongside William Wallace, and his son George is said to have been a follower of Robert the Bruce and who died at the battle of Dupplin in 1332. Notwithstanding these it did not stop James Dundas being involved in a long running dispute with the Abbot of Dunfermline in the 1300’s which could have resulted in excommunication! These lands remained in the Dundas family until 1449 when, like many estates at the time, they were forfeited to the crown. The land was restored to the family who found favour with James II and James III although this did not stop them being forfeited once again on the accession of James IV, albeit that they were quickly returned and in the late 1400’s Dundas Castle was built. George Dundas was the 16th Laird of Dundas and with his second wife Katherine Oliphant wished to purchase land for their eldest son James. The year was 1571 and Arniston was born. As you step through the entrance and follow the stone staircase from the porch you find yourself in the entrance hall. I was immediately struck by the height of the hall and the stunning stucco work on the ceiling, the faces of Dundas’s past looking down at you from portraits and marble busts. Whilst work on the current house commenced in 1726 a U shaped tower house had sat on the site of the current building. It is gone but not forgotten as the hall sits on the footprint of the old courtyard with the clock that was stood outside now nestling between two pillars. The clock itself, when include in the new building, had a custom made frame by the cabinet make Francis Brodie, who was none other than Deacon Brodie’s father! You can only imagine the turmoil that these walls would have witnessed with young James Dundas signing the great covenant in 1638. He was eventually reconciled with Charles II and allowed to become a judge on the reconstituted Court of Session. However, Charles II then demanded that all his subjects in public office sign a declaration renouncing the covenant. James refused and renounced his seat on the bench. In the early 1700’s Robert Dundas has a flourishing legal career which saw him rise to the position of Solicitor General and Lord Advocate. Being in these positions Robert felt that he required a more suitable residence and work on Arniston as it is now begins. Work started in 1726 with the renowned architect William Adam at the helm. The removal of the Tower House and the high wall that had previous surrounded it, opened up the views north to the Firth of Forth and to Fife, which on a clear day can still be enjoyed. The only part of the tower house that was retained were two rooms which were knocked together and now form, what I find, is the most atmospheric room in the house, the Oak Room. When you walk in and are greeted with the faces of Dundas’s past you can easily imagine the family and friends sitting in comfort with a glass of their favourite in hand. Indeed Sir Walter Scott once wrote “I always love to be in the old Oak Room at Arniston where I have drank many a merry bottle”. Winding your way up the main staircase, you find yourself in the gallery overlooking the entrance hall and from this vantage point the beauty of the stucco work is even more apparent. Continuing upwards the William Adam library is an impressive room. The walls covered in bookcases that would once have contained legal tomes and necessary reading of the times. These are now home to an equally impressive collection of porcelain, all of which are gazed down upon by terracotta busts. The views from the north facing windows look out over the once formal gardens to Edinburgh and beyond to Fife. As you descend from the library and down towards the entrance hall via the great staircase, where further family portraits adorn the walls, you can see one the unintended quirks of the house that was to arise with the approaching halt of building works. Robert Dundas was very keen to have extensive formal gardens around the house and in doing so inadvertently added to the houses character as in 1732 he ran out of money for the project. This was somewhat embarrassing as the west wing of the house had yet to be completed. It was not for another 20 years until his son Robert was married and married into wealth that the building could recommence. By this time William had died and it was over to his son John to see through the completion of the work. The change in architects resulted in a change of plans and rather than the extravagant state rooms that had initially been intended, a dining room and drawing room were created on the ground floor. In the late 1700’s the then Chief Baron made several changes to the house, adding a school room at the top of the house, with views to the south to where once a cascade would have proudly sat. This was similar to the famous cascade at Chatsworth and would have impressed guests who could look out from the porch in the Oak Room which was also added by the Chief Baron. Over the course of the house’s history each generation of Dundas’s have made their own mark on the house and continue to do so today. Indeed in 1957 the dining and drawing rooms were badly damaged by dry rot and it was 36 years before restoration on the dining room, and the drawing room 5 years later, was completed this time by the hand of Althea and another generation of Dundas’s have made their mark on this great house. The work continues as on the west side of the house sits the orangery which, having remained unused for the best part of 100 years is next on the list for attention. The house remarkable in itself is also full of remarkable items. With books dating back to the 15th century, stunning tapestries from the 16th century and a number of beautiful paintings, portraits and landscapes by the likes of Raeburn and Naysmyth. There are of course personal items on display and perhaps none more poignant than Hesters clock. This was commissioned following the death of Robert Dundas’s daughter Hester from diphtheria in the 1870’s and it is quite beautiful. Whilst I have tried to eloquently stitch together the intertwined story of the building and the family in this article, it is not a patch on the delivery of my guide Althea, whose extensive knowledge paints vivid pictures of the political forays and dealings of her ancestors and gives a very personal view of her family home. There is so much more to this fascinating story than I can do justice or indeed include here and I would highly recommend a visit should you have the opportunity to do so, to see and experience for yourself. It just goes to show, you never know what journey your research might take you on. Arniston House is open to the public during May and June on Tuesday and Wednesday with tours leaving at 2.00pm and 3.30pm. Then July to 13th September, on Tuesday, Wednesday and Sunday, with tours leaving at 2.00pm and 3.30pm. Visit www.arniston-house.co.uk for more information. The Albion badge. It amazes me, the journey a small find dug up in a Scottish field, can take you on. I came across a small badge with Albion on it and then found out it was a Scottish motor company. Here is what I found out. The Albion Motor Car Company Ltd. was established on the 30th of December, 1899. Albion Motors is Scotland’s best known name in the motor industry. However, its history goes right back to the first ever automobile manufactured in Scotland – and in Britain, for that matter – the Arrol-Johnston Mo-Car, later known as the ArrolAster, manufactured from 1896 to 1931 by the Arrol-Johnston Car Company Ltd. The Mo-Car was designed by George Johnston, a locomotive engineer, and his joint venture with bridge engineer, Sir William Arrol, which began in 1895 as the Mo-Car Syndicate Ltd., employed two men who would go on to start Albion Motors four years later. Those two men were Johnston’s cousin, Norman Osborne Fulton, and Dr. Thomas Blackwood Murray, both of whom had been employed by Mavor and Coulson, makers of electrical and mining machinery in Bridgeton, where Fulton had been Works Manager and Murray, Manager of the Installation Department. At Arrol-Johnston, Fulton was made responsible for manufacture and assembly, whilst Murray’s electrical experience became invaluable as his first task was the development of electrical ignition in place of the incandescent platinum tubes of the Daimler engine. On the 30th of December, 1899, Murray and Fulton entered into a partnership of their own and established the Albion Motor Car Company Ltd. in Glasgow, a city already renowned worldwide for its engineering excellence. Those two entrepreneurs were joined a couple of years later by John F. Henderson, who provided additional capital. Originally, Albion’s factory was on the first floor of a building in Finnieston Street, and it began with just seven employees. Later, in 1903, the company moved to new premises in Scotstoun and became one of the largest, purely engineering firms in Glasgow, employing 1,800 people. Albion also became renowned for its superior engineering and reliability, and its name appeared on vehicles between 1899 and 1975. Its slogan, ‘Sure as the Sunrise’, was adapted into the logo that featured on the radiator and badges of its models for many years and that helped to establish Albion’s identity wherever its vehicles were exported throughout the world. At the beginning of the 20th Century, cars were hand built and they were expensive to buy. Things were very different from the large factories that we today associate with car production. In those days, before automation, computers and robots, cars were built by small teams of highly skilled craftsmen and women. Albion built its first private motor car 1900. That was a rustic-looking, solid tyred dogcart made of varnished wood and powered by a flat-twin, 8hp engine with tiller steering and gear-change by ‘Patent Combination Clutches’, and it cost £400. In 1903, Albion introduced a 3115cc, 16hp vertical-twin, followed in 1906 by a 24hp four cylinder engine. One of the early custom models that Albion offered was a solid-tired, shooting-brake, which was a kind of luxury estate car with a pair of side hinged rear doors that were designed for use by hunters and other sportsmen who needed easy access to a larger boot space. The last private ‘Albion’ was the A3 Model tourer, powered by a 16hp monobloc, four cylinder engine of 2492cc. At first, the firm made motor cars and, from 1909, commercial vehicles, however, from 1913, it concentrated on the latter, which helped it to survive the difficult years after the First World War. In fact, during World War I, Albion’s premises were enlarged to produce military vehicles and it built large quantities of 3-ton trucks, which were powered by a 32hp engine using chain drive to the rear wheels. After the war, many of those trucks were converted for use as charabancs. Later, in 1920, the company announced that estate cars were to be available once more, based on a small bus chassis, but it is not known if any were actually made. The earliest buses were built on truck chassis and it is known that two were delivered to West Bromwich in 1914 and, although Albion didn’t produce a purpose built, double decker chassis until 1932, it did deliver a few of those to the city of Newcastle upon Tyne prior to 1920. In 1923, Albion’s first dedicated bus chassis was announced. Derived from its 25cwt truck chassis, but with better springing, it had seating options for between 12 and 23 passengers. A lower frame chassis, the Model 26, with 30/60hp engine and wheelbases from 135 inches to 192 inches joined the range in 1925. All those early vehicles had the engine in front of the driver, but in 1927, the ‘Viking’, the first forward control bus, with the engine alongside the driver, allowing 32 seats to be fitted, was announced. The first true double decker design was the ‘Venturer’, with up to 51 seats. The ‘CX’ version of the chassis was launched in 1937 and on those the engine and gearbox were mounted together, rather than joined by a separate drive shaft. Albion introduced a range of diesel engines, initially from Gardner, from 1933. By which time, the Albion Motor Car Company Ltd. had been renamed Albion Motors, a name change that occured in 1930. After World War II, Albion’s range was progressively modernised and underfloor engined models were introduced with two prototypes in 1951. That led to the ‘Nimbus’, which appeared in production models from 1955. Complete trucks, and single and double decker buses, were built in the Scotstoun works until 1972 and the firm’s buses were exported to Asia, Australia, East Africa, India and South Africa. Almost all Albion buses were given names beginning with ‘V’, such as the ‘Victor’, ‘Valiant’, ‘Viking’, ‘Valkyrie’, and ‘Venturer’, except for the ‘Nimbus’ and the ‘Aberdonian’, which was designed to be the lightest, full size, underfloor engined bus. The ‘Aberdonian’ was a much more economic, in terms of fuel consumption, derivative of the ‘Nimbus’ and it was built between 1957 and 1960. In 1957, Lancashire-based Leyland Motors acquired Albion Motors as the first step in an expansionist policy, which saw famous names like Scammell, A.E.C. and Guy sucumb. Albion Motor’s name was changed, rather ignominiously, to Leyland (Glasgow) and later, in 1987, to Leyland-DAF. Then, in 1993, a management buy-out brought Albion Automotive, as it then became known, back into Scottish ownership. Since 1998, Albion Automotive has been a subsidiary of American Axle & Manufacturing, and manufactures axles, driveline systems, chassis systems, crankshafts and chassis components out of its premises on South Street, which it took over from the neighbouring Coventry Ordnance Works in 1969. Today, you can visit the Albion Archive, in Biggar, where Thomas Blackwood Murray originally lived. You can also visit the annual Veteran & Vintage Vehicle Rally at the showfield in Biggar, which is held in honour of the Albion Motor Car Company and its founders. It always amazes me the roads and paths the things we dig up take us down. Have you found anything you like recently? We are looking for photos of things found to go into our magazine. Send a photo of it to [email protected] with your name and we will put the photo in the magazine for everyone to see. Do you have anything you want published in this magazine email it to [email protected] Editor’s Ramblings..............................................2 Detecting Scotland Dig96……………………....3/4 The Antonine Guard……………………………..6/9 Under the Spotlight Bob McGarry………….11/12 Detecting Scotland dig 100 Charity dig for Cot Death …………………...13/20 The Ring Pull………………………………………21 Lincolshire Trip 2015…………………………22/25 Update on the seal found at Detecting Scotland dig100……………………………..…………….27/28 From buried treasure to hidden gem……...29/32 The Albion Badge …………………………….34/36 The people that put this magazine together do so in their own time and do it without payment. It takes a lot of time and effort to put this magazine together so if you want to use any of the articles in this magazine please ask permission first by emailing: [email protected] thank you Visit our website on www.upyerkiltmagazine.co.uk Join us on facebook now www.facebook/upyerkiltmagazine

© Copyright 2026