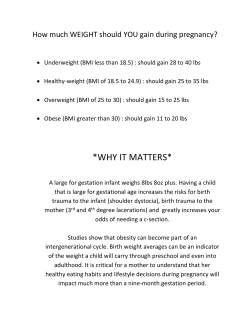

EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ECONOMIC